Low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) have rebounded strongly since the COVID-19 pandemic. Gross national income (GNI) among these countries was resilient in 2023, at $36 trillion — and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that economic growth of developing economies will hold steady at about 4 percent over the next two years.

Yet LMICs face a new challenge that, coupled with the significant amount of new debt they accumulated during the pandemic, could create headwinds to growth and development going forward.

Growing trade protectionism is increasing global trade policy uncertainty and is anticipated to weigh materially on demand for exports from developing economies. The IMF projects that increased trade protections could reduce global economic output by as much as 7 percent over the long term.

Many LMICs rely on access to global markets to grow their economies, create sufficient employment for rapidly expanding working-age populations, and enhance development. So, a slowdown in global trade is a challenge for these countries at any time.

Today, however, growing trade frictions pose an additional challenge. LMICs accumulated a considerable amount of debt during the pandemic — their overall debt level rose from 26 percent of GNI before the pandemic (in 2019) to 28 percent in 2020. And revenue from exports is critical to servicing these larger debt burdens.

The debt-to-export ratio, which compares total debt stock to export income, has increased for all LMICs. It has risen particularly sharply for IDA borrowers — a group of 78 low-income countries — due to a steeper increase in these countries’ debt levels during the COVID crisis.

Total debt for IBRD borrowers (excluding China) increased by an average of 3.6 percent annually from 2013 to 2023, while IDA borrowers’ debt increased 8.2 percent annually (on average) over the same period. (The World Bank’s International Debt Statistics includes 63 IBRD borrowing countries that are primarily middle-income and creditworthy low-income countries.) IDA borrowers’ debt more than doubled from 2013 to 2023, from $521 billion to $1.1 trillion, driving their debt-to-export ratio from 117 percent in 2013 to 190 percent in 2023.

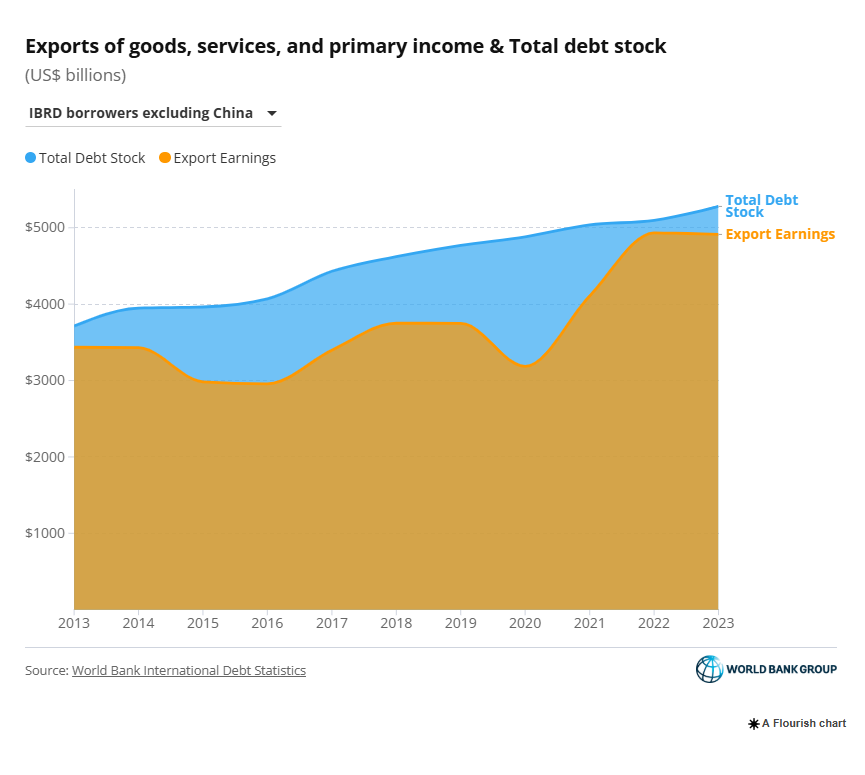

The debt-to-export ratio of IBRD borrowers’ (excluding China) increased from 108 percent in 2013 to 153 percent in 2020 and then returned to its 2013 level by 2023 thanks to a dramatic recovery of exports from 2021 to 2023. Exports of IBRD borrowers jumped 54 percent over three years from 2020 to 2023.

For IDA borrowers, the debt-to-export ratio reached a decade high of 240 percent in 2020 at the onslaught of the pandemic. It too, has recovered since, but not by as much as that of IBRD borrowers.

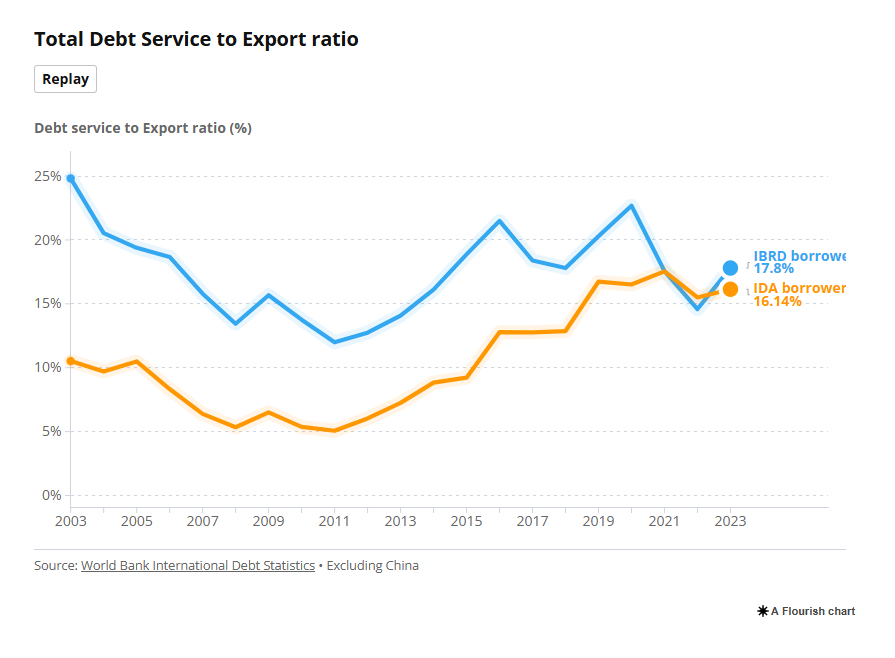

And the ratio of debt service to exports among World Bank borrowers, which compares principal and interest payments to export income, spiked during the pandemic years, too, though it fell slightly as exports began to recover after the worst of the crisis receded. LMICs’ export earnings fell 15 percent in 2020, to $3.6 trillion, but then recovered 53 percent by 2023, to about $5.5 trillion.

Still, the debt service-to-export ratios for both IBRD borrowers (excluding China) and IDA borrowers remain high by historical standards, at 17.8 percent for IBRD borrowers and 16.1 percent for IDA borrowers.

For example, Bangladesh, an IDA borrower heavily reliant on exports of mostly textile products, saw exports drop by 28 percent in 2020, while its total debt outstanding increased during the pandemic, from $74 billion in 2019 to $101 billion in 2023. That sent the South Asian nation’s debt-to-export ratio soaring to 190 percent in 2020. And while its debt-to-export ratio has decreased since the COVID era, a persistent increase in debt kept it elevated, at 171 percent in 2023. That is significantly higher than its pre-pandemic level of 138 percent.

For larger LMIC economies, export earnings have mostly recovered from the pandemic slump and now exceed pre-pandemic levels. Export earnings among the top nine LMIC exporters excluding China — they are India, Mexico, Brazil, Vietnam, Türkiye, Thailand, Indonesia, South Africa, and the Philippines — climbed 33 percent from 2019 to 2023.

India and Vietnam are two of the biggest drivers of the LMIC export recovery. India’s exports grew 57 percent from 2020 to 2023, from $507 billion to $811 billion, and that growth kept its 2023 debt-to-export ratio at 80 percent despite soaring external debt. Vietnam’s debt-to-export ratio dropped 9 percentage points, to 37 percent, in 2023, even though the country added significant new debt, most of it through private borrowing.

Overall, the post-pandemic period is a mixed bag for LMICs in terms of debt and exports.

While many larger economies have experienced a healthy rebound in export earnings and market access, others continue to face significant challenges. And the diverse capacities of LMICs to manage debt levels and navigate trade volatility raise concerns about their long-term economic health and sustainability.

In this new era of global economic fragmentation, strengthening LMICs’ resilience and boosting development will require enhanced adaptability to changing global trade winds, in addition to managing higher debt levels. The World Bank’s International Debt Report (IDR) supports policymakers and analysts by monitoring aggregate and country-specific trends of LMICs’ external debt. Users can access the data through a variety of sources, including DataBank and our online statistical tables.

Source : World Bank