Europe’s reliance on US arms raises autonomy concerns, as security worsens and leaders aim to cut strategic and technological dependence.

Worries about Europe’s dependence on the United States military industrial base have increased with the worsening security situation in Europe and the deterioration of the transatlantic relationship. With a new dataset covering all US foreign military sales notifications since 2008, we show that Europe has substantially increased its purchases from the US defence industrial base during the last four years, deepening its dependence on US military equipment in the short to medium term.

The dependence is particularly significant for high-tech equipment, including air defence, missiles and fighter jets, and for additional equipment and services included in purchases, such as advanced software and sustainment and modernisation required in future years.

This strategic reliance on the US, even when the risks associated are low, provide the US with significant bargaining leverage over Europe that can potentially be used in different policy areas, such as trade. Moreover, the US military industrial base faces its own constraints and current and future US administrations might prioritise deliveries to Asia.

In response, European policymakers must assess the extent of dependence on the US and develop a strategy on how to minimise the risks. At a time of rising defence budgets, it is crucial that European production of key weapon systems grows faster than demand, so that dependence on the US defence industrial base is gradually reduced. Policymakers should review critical technological dependencies, even for procurement directed at national producers, and should plan to upgrade Europe’s technological base without increasing external dependence. Learning from and cooperating with Ukraine to boost Ukrainian production is one important step. Establishing a timeline to determine the pace at which certain dependencies should be minimised is equally necessary. Europe also needs to reduce its reliance on structural strategic systems provided by the US, such as command, control and communications systems.

Given the diverging strategic cultures across Europe, building consensus is of paramount importance. European companies need to grow to the scale that is only achievable in a larger market. Failing to implement a strategy risks Europe losing its freedom and autonomy.

1 Introduction

Vladimir Putin’s Russia continues to be a formidable threat to Europe. The number of active-duty troops in Russia is set to increase to 1.5 million, and military production has reached record highs (Burilkov et al, 2025). If the current trajectory continues, Russia will have the world’s second largest standing army after China, which continues to massively increase its own military capability.

Europe faces this deteriorating threat scenario at a moment of huge disruption in the transatlantic relationship. Transatlantic relations have gone through different stages, but Sapir et al (2025), for example, argue that the current disruption goes beyond the ups and downs in the relationship in the past. There are even fears that the United States may become an autocracy without free elections .

The state of transatlantic relations has implications for the transatlantic trade in defence products. Calls for more European independence in this context are not new but have not so far led to major policy changes . The idea of ‘too much’ European independence has even been rejected. In 1998, then US secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, argued that “decoupling” would weaken the alliance, “duplication” would spread resources too thinly and “discrimination” against non-EU producers would be undesirable .

Albright made these points when US growth and fiscal strength were superior to today. Now, there is a serious question of whether the US has the fiscal capacity to sustain a long-term global military presence at approximately current levels. Now, the question, even on purely economic terms, is whether NATO’s current force posture can survive the inevitable US fiscal consolidation while European rearmament takes place.

Beyond purely economic arguments, many European politicians worry about excessive dependence on the US. There is concern that defence dependence translates into unfavourable trade relations . There are also worries that the security guarantees for Europe that the US provides via NATO may be at risk, irrespective of whether US demands on trade are accommodated.

Europe’s security dependence on the US is multi-faceted. Many European countries depend on the US to take a political lead on global affairs. They also depend on the US nuclear umbrella, the presence of US troops in Europe, the sharing of US intelligence with European allies, US support for Ukraine, specific US technologies, the sharing of patents and finally US weapons. In this Policy Brief, we focus on EU reliance on US weapon supplies.

In financial terms, the US is the world’s largest exporter of weapons. Its large domestic market for defence products, combined with sales to numerous countries, has provided US companies with substantial scale to develop leading modern weapon systems. A huge US annual research budget of roughly $150 billion has further added to the advantage. Sophisticated weapon systems from the US are in high demand in Europe, Asia and the Middle East, but in recent years, Europe has become an increasingly important customer.

The US organises the main transfers abroad of military equipment primarily through its Foreign Military Sales (FMS) programme . Between 2017 and 2021, the FMS portfolio for the US’s European allies averaged $11 billion, but in 2024, it reached $68 billion (Cavoli, 2025) . This growth in demand is unsurprising: after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, European countries increased their defence spending substantially from only 1.3 percent of GDP in 2016 to now above 2 percent. As defence budgets have increased, spending on military equipment has increased particularly strongly, more than doubling to about 0.7 percent of GDP now. Faced with an initially relatively small domestic military production base, it is natural for EU countries to direct more demand to the US defence industrial base – at least until European domestic production can be scaled up. Beyond the increase in overall demand, there is also a modernisation need, for example the replacement of old fighter jets with new models. Europe is thus becoming more, not less, dependent on the US. But what form is this increased dependency taking, and to what extent should it be a concern?

US foreign military sales are subject to intricate foreign-policy considerations in the US . For example, President Donald Trump has suggested that only new fighter jets with downgraded capabilities should be sold to allies . US Under Secretary of War for Policy, Elbridge Colby, has repeatedly argued that US weapons should be prioritised for use by US forces and allies in Asia . However, the US has been inconsistent, as can be seen from the contrasting arguments made by the US ambassador to NATO, who has called repeatedly for continued European purchases from the US .

In response to some of these political and strategic uncertainties, the US’s allies in both Europe and Asia have been thinking about cancelling orders of prominent US weapon programmes, such as the F-35 . In reaction to uncertainty about US foreign military sales policy, Denmark even decided to buy a €7.8 billion air defence system from European suppliers instead of US suppliers .

Against this backdrop, this Policy Brief assesses how dependent Europe is on US foreign military sales and identifies to what extent this dependency is a source of concern. It provides numbers on US foreign military sales to Europe and the types of technology for which Europe depends on the US. It then formulates policy recommendations.

2 Should Europe worry about weapon imports?

Europe and many parts of the world have long relied on imported weapons (Mejino-López and Wolff, 2025), with the US often the main partner. An important part of that bargain was the implicit security guarantee granted by the US. Assessing how vulnerable Europe is now in the context of that dependency requires evaluation of multiple aspects of the relationship.

The first aspect is overall volumes. Large imports from the US would indicate that Europe’s domestic defence industry is too small, possibly losing out in terms of jobs and innovation capacity, and perhaps even implying an inability to build weapons at scale when needed. A debate on this volume aspect has emerged since the publication by the European Commission in March 2024 of the European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS; European Commission/HRVP, 2024) and the suggestion in Draghi (2024) that almost 80 percent of Europe’s military procurement was directed towards foreign suppliers. The debate has been, however, fraught with misunderstandings and incorrectly interpreted data. Mejino-López and Wolff (2024a) and Burilkov et al (2025) clarified the numbers and showed that, in terms of imports, Europe’s dependence on foreign suppliers is much less. European governments, with major exceptions such as Poland, typically buy from domestic producers.

Studying dependence solely through the lens of imports misses important aspects; imports measured in billions of euros are not a good measure of actual dependence on the US military industrial base. For example, this indicator does not capture the many weapons bought from US producers’ European production sites, sometimes made in cooperation with local companies. Burilkov et al (2025) showed, based on Wolff et al (2025), that national and foreign partnerships represent a substantial percentage of military procurement, often around 30 percent. Simple import statistics thus fail to capture the extent of dependence on US companies with respect to purchased volumes.

A second aspect concerns technological dependence. Import statistics do not capture the critical importance of specific technology. This may be just a small intermediary product, component or software not appearing as significant in import statistics, but critical for the functioning of entire weapons systems, for example through command-and-control systems. European countries have the capacity to produce much military equipment, but still rely heavily on the US for software, the provision of strategic enablers and specific major equipment (Burilkov et al, 2025).

Third, worries in Europe about dependence on US weapons systems extend well beyond weapons deliveries. Senior politicians from Portugal, Switzerland and Denmark have talked publicly about the possibility of ‘kill switches’, or automatic means of disabling equipment . Deals between the United Kingdom and Nordic countries on production of warships might have come about in part because of these security concerns. US defence companies have denied the existence of such kill switches for their weapons, but President Trump has stated that lower-capacity versions of some weapons should be sold to allies because they may not remain allies (see section 1, footnote 8).

The need to update weapon software regularly represents a risk. F-35 fighter jets rely on the ODIN software, for example, while several European navies rely on the American Aegis Combat System. Should the software components of these integrated systems for some reason not be updated, the effectiveness of modern warships would be diminished. Another example in which software dependence may have had direct military implications, is a reported decision by Microsoft to discontinue certain services for Israel’s military over surveillance of Palestinian civilians . Reliance on cloud services is a further possible source of vulnerability.

Box 1: The F-35 programme

The programme to develop the US fifth-generation fighter aircraft is an example of cooperation between the US and foreign governments. It also demonstrates the security risks. The UK, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway have participated in research and development related to the F-35. The European contributors also participate in the supply chain. These countries can acquire F-35s under a different legal basis to the FMS (see CRS, 2022, for more details). The main contractors associated with the programme are Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman (both US) and BAE Systems (UK).

While most F-35 manufacturing is done by US contractors located in the US, the extensive net of suppliers numbers almost 2000, varying in size and from different countries . Italy and Japan have facilities for final assembly of F-35s, with the Italian facility producing aircraft for the Italian and Dutch markets.

Though US dominance in terms of producing and owning the key assets needed for F35 production represents a security risk for the European allies, their involvement in the supply chains provides some reassurance by providing some (albeit limited) leverage over the US. For instance, the suspension of Turkey from the programme in 2019 forced US industry to find new providers for more than a thousand parts (GAO, 2020). Failure of European providers in the supply chain for whatever reason would also create disruption; BAE Systems (UK), for example, provides key software components, while Alenia Aermacchi, a Leonardo subsidiary (Italy), produces a significant share of the aircraft wings. Realistically, however, the escalation dominance would be with the US.

FMS notifications for F-35s often involve high volumes of related equipment, included either in the same sale and/or at a later point. This is the case for AIM-120C-8 Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAM), produced by RTX (US), with sales to Germany and Poland alone amounting to more than 800 missiles. The maintenance of the aircraft also involves the participation of US contractors. The UK, for example, contracted maintenance services for €185 million in 2023 for a fleet of 37 aircraft (Wolff et al, 2025a). In August 2025, an FMS notification for Poland shows F-35 sustainment services worth $1.85 billion.

Fourth, maintaining an integrated transatlantic defence industrial base, as for example advocated by Caverly and Kapstein (2025), implies accepting supply-chain dependence that will likely be asymmetric. The F-35 programme is a prime example of an integrated transatlantic supply chain with substantial asymmetries. While several important parts of the F-35 are produced in Europe, ultimate control over production and sales remains with the US.

There have been instances of the US preventing a partner country from buying F-35s (Turkey; Box 1) and the US eventually replacing that partner’s contribution to the F-35 supply chain by turning to alternative suppliers. European suppliers control some key parts of production. For example, joint strike missiles are produced exclusively by the Norwegian company Kongsberg. But European partners are unlikely to be able to equally credibly threaten to disrupt the F-35 supply chain (Box 1). Supply chains involve mutual dependencies, but in politically difficult times, the US would probably be able to replace European components, such as joint strike missiles, rapidly, while European nations cannot quickly replace F-35s. The purchase of numerous F-35 fighter jets by multiple European governments has locked-in European air forces to US technology that would be difficult, or at least expensive, to exit from. Many governments increasingly see this as a vulnerability .

Finally, continuous reliance on the US defence industrial base means it is difficult to reach sufficient scale in the European defence market for expensive high-tech products. While the French Rafale and Swedish Gripen fighter jets may be European, the Gripen at least relies on crucial components (the engine) supplied by the US . If European countries want to create very expensive top-notch products that are independent of the US industrial base, European market scale must be combined with standardised exporting policies.

3 Analysing European reliance on US FMS

US military equipment exports are governed by national security and foreign policy laws and regulations, including the Foreign Assistance Act and the Arms Export Control Act. These provide the legal framework for the export channels used by the US government, mainly the Foreign Military Sales. FMS is the central instrument for the sale of US weapons abroad. It is quantitatively and in terms of strategic relevance much more important that the Direct Commercial Sales and the Foreign Military Financing instruments (appendix 1).

The FMS consists of government-to-government agreements, with the US administration playing an intermediary role between the foreign government and US contractors. Under the FMS, the foreign government depends on the US administration to negotiate the conditions of the contracts with the defence companies. The FMS is typically the instrument used for exports of the most advanced military equipment, including fighter aircraft, autonomous equipment and advanced missile systems .

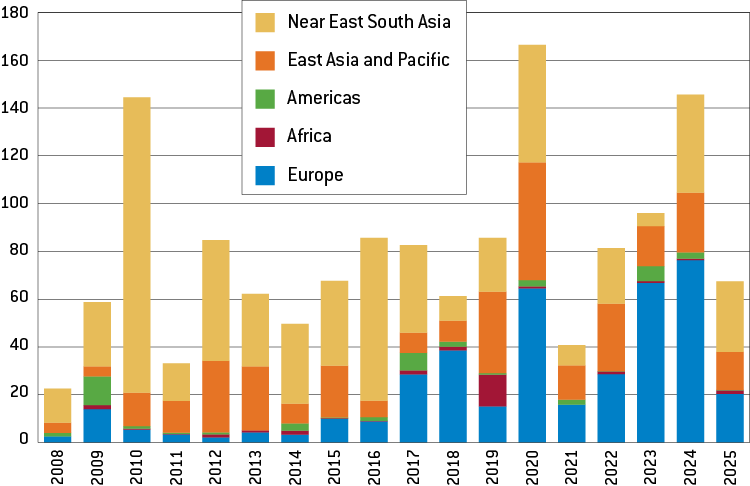

Mejino-López and Wolff (2025) compiled, for the first time, a database of all 1179 FMS notifications published by the US Department of Defense between 2008 to 2025. Until 2017, only a small part of the FMS notifications related to Europe, reflecting the very limited European spending on defence equipment (Wolff et al, 2024). Since 2017, however, Europe has accounted for a larger share of FMS sales, often being the continent with the largest share (Figure 1) .

FMS notifications involving European countries first showed a sharp increase in 2020 because of major acquisitions of F-35s and F-18s by Finland and Switzerland. In 2024, the number of notifications increased further to a record high for European customers, reaching $76 billion, four times the European average since 2008. If current numbers persist, Europe is set to account for a very substantial part of advanced US military equipment exports.

Figure 1: FMS notifications by destination region, $ billions, 2024 prices

Source: Bruegel based on Mejino-López and Wolff (2025).

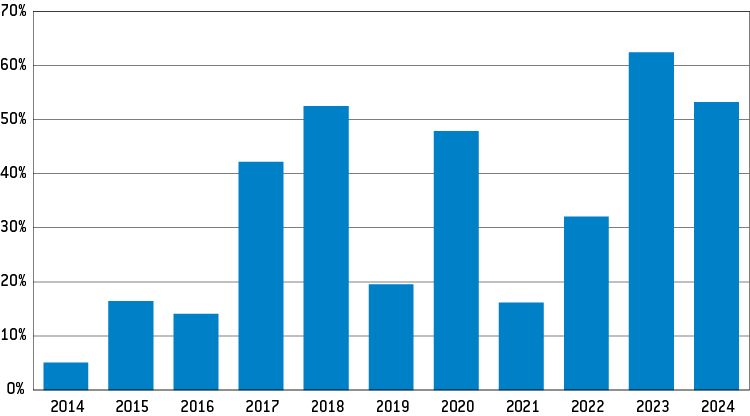

As European defence budgets and equipment purchases have increased, European countries have directed their massive increase in demand to both domestic and foreign producers. For European NATO countries as a whole, FMS notifications from 2022 to 2024 represented 50.7 percent of their spending on military equipment. This compares to 27.83 percent from 2019 to 2021. Figure 2 plots how FMS has become more important in Europe’s overall equipment spending.

However, FMS notifications do not mean immediate sales . Delivery and disbursement of funds can come years later. Burilkov et al (2024) provided selected evidence of delivery delays. Delays can result from high demand relative to US production capacity, as is the case for expensive Patriot air defence systems. Political considerations can lead to reprioritisation of which countries receive deliveries first or go to the back of the queue. Patriot deliveries to Switzerland, for example, have been delayed in order to prioritise deliveries to Germany, which has delivered the systems to Ukraine .

Moreover, FMS notifications do not automatically translate into US exports, as some of the products and services under FMS are produced and provided in Europe. Burilkov et al (2025) showed that from the perspective of procurement, a substantial share of spending is directed to joint venture companies that have production sites in Europe. Therefore, actual exports that appear in trade statistics are substantially smaller and the importance of weapons sales for the US’s bilateral trade balances should not be exaggerated.

Figure 2: FMS notifications for NATO Europe as a share of NATO Europe equipment spending

Source: Bruegel based on NATO and Mejino-López and Wolff (2025).

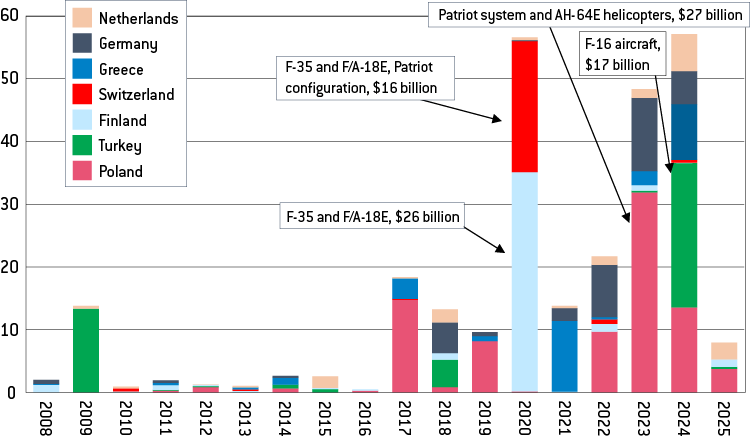

Within Europe, there is substantial variation in purchases via the US FMS programme. Poland’s FMS notifications account for a large part of overall US FMS sales to Europe (Figure 3). From 2022 to 2024, Polish purchases amounted to over $55 billion, or 30 percent of European demand. Polish purchases have driven the sharp rise in European notifications since 2020, with its FMS notifications representing 106.83 percent of its overall defence procurement according to Wolff et al (2025). FMS notifications in a given year do not match precise procurement spending in national budget data as notifications precede the actual deal, let alone delivery. Nevertheless, these numbers indicate just how striking the Polish armament strategy is . Finland, Turkey and Switzerland, and to some extent Germany and Greece, are the other main countries to have negotiated military purchases from the US. For Germany, FMS notifications represented only 19.63 percent of its overall defence procurement from 2022 to 2024, according to the numbers in Wolff et al (2025).

Figure 3: Value of FMS notifications for Europe, $ billions, constant 2024 prices

Source: Bruegel based on Mejino-López and Wolff (2025).

Figure 3 also provides an insight into the type of equipment purchased under the FMS. Major F-35 purchases preceded the war in Ukraine and reflect the ongoing modernisation of European air forces.

Table 1 shows all FMS notifications involving European countries worth $5 billion or more since 2020. Such large notifications primarily relate to aircraft and air-defence systems and missiles.

The high level of detail of the data also allows us to see associated services or other equipment included in deals. For example, a major sale notification for Turkey includes 40 new F-16 aircraft and the modernisation of 79 F-16s. The notification also covers radar systems, cryptographic devices, electronic warfare systems and medium range air-to-air missiles. Notifications of sales to Finland included, besides F-35s, tactical missiles, bombs and intelligence devices. Similarly, the notification for a sale to Poland included both 644 Patriot missiles and 48 Patriot launch stations.

Table 1: FMS notifications to European countries exceeding $5 billion since 2020

| Country | Main equipment | $ bns | |

| Turkey | F-16 Aircraft | 23 | |

| Poland | Integrated Air and Missile Defence Battle Command System (IAMD, IBCS) | 15 | |

| Finland | F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and EA-18G Growler aircraft | 15 | |

| Finland | F-35 Joint Strike fighter aircraft | 13 | |

| Poland | AH-64E Apache helicopters | 12 | |

| Greece | F-35 Joint Strike fighter aircraft | 9 | |

| Germany | CH-47F Chinook helicopters | 9 | |

| Germany | F-35 Aircraft | 8 | |

| Switzerland | F/A-18E/F Super Hornet aircraft | 7 | |

| Poland | F-16 Viper midlife upgrade | 7 | |

| Romania | F-35A Lightning II Joint Strike fighter aircraft | 7 | |

| Greece | Multi-Mission Surface Combatant (MMSC) ships | 7 | |

| Switzerland | F-35 Joint Strike fighter aircraft | 7 | |

| Poland | M1A2 SEPv3 main battle tanks | 6 | |

| Czechia | F-35 Aircraft | 6 | |

| Germany | Patriot Advanced Capability-3 Missile Segment Enhancement Missiles | 5 | |

Source: Bruegel based on Mejino-López and Wolff (2025).

4 Addressing Europe’s dependence on FMS

Analysis of our new FMS database shows that several European countries have substantially increased purchases from the US military industrial base. This is, in part, a matter of availability of certain technologies: the US produces some weapons systems that are unrivalled by European producers, such as the fifth-generation fighter jet (F-35), long-range rocket artillery (Multiple Launch Rocket System, MLRS) and some long-range missiles. In part, however, increased purchasing from the US is a deliberate geopolitical decision based on the assumption and hope that purchases will ensure continued US commitment to European security .

However, the evidence provided in this Policy Brief demonstrates that while Europe currently benefits from US imports, there are material dependencies that lead to substantial economic and geopolitical dependencies. The mere existence of a high security risk to Europe, even if of low probability, fundamentally impacts the balance in the transatlantic relationship. In a context of new political uncertainty, this should invite serious reflection. In addition, US production capacity constraints and the increasing risks in the Asian theatre (Colby, 2021) may further jeopardise the continuation of weapon deliveries from the US.

In our assessment, European policymakers therefore need to assess their dependence on US supplies of weapon systems critical for Europe’s self-defence, and to develop a strategy on how to reduce it. Such a strategy will need to weigh up difficult trade-offs.

The first is Europe’s ability to master cutting-edge technologies. Currently, European countries do not produce certain weapons systems, relying instead on the US industrial base. Given that the US defence R&D budget of $150 billion in 2024 far exceeds Europe’s budget of around €11 billion in 2023, the technology gap will be difficult to close across all weapons systems.

A credible strategy to reduce arms imports from the US must deal with this problem. While this is a question for military planners, the rapid change in the way wars are fought, as seen in Ukraine, represents an opportunity for Europe to partner with producers in Ukraine and with leading companies in Western Europe, and to focus scarce resources increasingly on drone and missile warfare. Further areas of focus should be advanced communication and integrated combat systems, and artificial-intelligence and satellite-based intelligence. New partnerships with emerging US high-tech companies should be deprioritised.

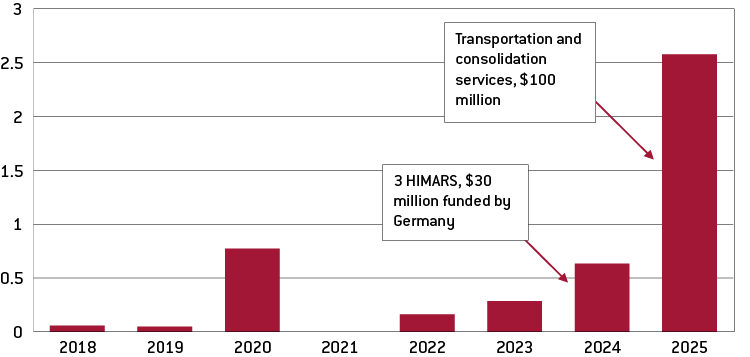

The second important issue is that Europe’s security continues to depend on US supplies to Ukraine. The US has provided weapons to Ukraine outside of the FMS using the Presidential Drawdown Authority, under which the US president can draw directly on Department of Defense stocks and deliver them to Ukraine . The US was the biggest military and financial donor to Ukraine until 2024, but Europe has now taken the lead. Under the second Trump administration, the US relationship with Ukraine has become more transactional, and the military equipment transferred now seems to be switching from special instruments (such as the Presidential Drawdown Authority and the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative) to the standard exporting vehicles used for other allies. The almost fivefold increase in FMS notifications involving Ukraine between 2024 and 2025 seems to corroborate this point, indicating that now either Ukraine or its European allies must fully finance any military support from the US. Meanwhile, actual US defence supplies delivered to Ukraine – air defence, for example – appear to be declining. Dealing with possible disruption of US supplies to Ukraine thus remains a top European priority. Further strengthening the Ukrainian industrial base should be an essential part of the response (Kirkegaard, 2025).

Figure 4: FMS notifications for Ukraine since 2018, $ billions, 2024 prices

Source: Bruegel based on Mejino-López and Wolff (2025). Note: the chart shows that under President Trump, FMS notifications to Ukraine have gone up. This does not mean that actual deliveries have gone up but rather suggests that previous schemes to transfer weapons to Ukraine, such as US Presidential Drawdown Authority, are being replaced by the commercial FMS.

The third important issue is the timeline. European countries have substantially increased weapons purchases from the US since 2020. There was arguably no alternative, given the lack of domestic production capacities for systems that European companies produce and for systems for which no European equivalent technology exists . Relying on US producers was also seen as necessary because European policymakers wanted to ensure that their militaries could build up their capabilities to be ready to confront Russia in 2030 – mentioned by NATO and defence ministers as when Russia would be prepared to attack a European NATO country .

However, strong reliance on US production for rapid rearmament creates lock-in effects that will favour US producers over the long term, making the creation of domestic alternatives more difficult. European policymakers should thus plan a longer rearmament timeline for selected weapons to allow domestic producers to develop and produce such systems. This might not actually delay actual rearmament, given the increasing delays in some US weapons deliveries (Burilkov et al, 2024).

5 Recommendations

European policymakers worry about the security of their countries because of Russia’s aggressive posture. Europe is benefiting from US weapons and the US security guarantees through NATO. However, dependence on US weapon deliveries and embedded technology is a growing concern. Even though extreme scenarios, in which intelligence sharing would be discontinued or weapon systems not updated, therefore becoming much less effective, might be unlikely, the mere existence of that possibility provides the US with leverage across multiple policy areas. We therefore argue that a strategy needs to be developed and implemented on how to reduce the most problematic dependencies.

Reducing dependence on the US FMS at a moment of high intensity warfare on the European continent requires a substantial increase in the output of the European defence industrial base. To boost domestic production, European companies need a clear view of how future demand will develop. The debt-funded defence spending increase in Germany (Zettelmeyer, 2025) will drive overall demand for European defence products. In some parts of Europe, however, the fiscal outlook is much less certain and therefore it may be difficult to raise defence spending substantially, despite declarations to the contrary in the NATO context.

Policymakers should thus design and implement a strategy to determine how spending increases across Europe will be financed sustainably, and how the distribution of spending will shift gradually to European suppliers and European equipment overall. Given that defence budgets are still set to grow, spending more on European producers does not necessarily lead to reduced imports from the US. Policymakers need to understand and argue that this is a unique possibility to strengthen the European defence industrial base without undermining purchases from the US, thus containing the possible political fallout for the transatlantic relationship.

Second, by increasing spending on US military technology, Europe has reinforced US dominance in some technologies, providing it with additional demand and profits. This has created a situation in which, despite bigger European spending, the US’s technological lead may be growing.

To boost domestic technological alternatives, European start-ups and unicorns, working at the cutting edge of new technologies such as drones, automated weapon systems and advanced missile systems, need a clear prospect of incoming demand. Several new companies have already emerged . Improving their growth prospects is not primarily a question of ensuring sizeable and growing defence budgets. Rather, it is a question of procurement authorities modernising rapidly and understanding the evolving military technological needs. In Wolff et al (2025), we did not detect major shifts in spending towards new technologies that have been deployed successfully in Ukraine. From a policy perspective, procurement authorities should be prepared to finance prototype development, provide testing facilities, offer direct connections between startups and military units, and provide purchase guarantees when new systems are successfully tested to alleviate the funding constraints faced by relatively new companies. Some degree of European preference, especially for high-tech products, is needed to ensure new tech demand boosts European producers.

More controversially, European militaries, procurement agencies and their political masters need urgently to review critical technological dependencies, even for procurement directed at national producers. For software, for example (section 2), policymakers should review whether dependence on AEGIS or ODIN systems is really still appropriate in the new transatlantic context, especially when ordering new major equipment from domestic producers, such as German F127 frigates . In short, supply chains need to be reviewed and future-proofed for an age of geopolitical turbulence.

Moreover, independent European production is also essential because even the US does not yet have some new state-of-the-art technologies such as controllable hypersonic weapons, on which Russia and China seem to be ahead . Europe must regain technological leadership and that requires targeted investment and purchases from domestic industrial leaders and start-ups. A defence industrial strategy focusing on scale, research and some degree of European preference is an essential element for upgrading and expanding European production (Mejino-López and Wolff, 2024b).

Third, European policymakers must tackle the fragmentation of their domestic defence markets to achieve the scale necessary to produce expensive advanced systems. For example, sharing the burden across several European countries would greatly reduce costs per country of developing strategic enablers that are currently not owned or controlled by Europeans, such as advanced command, control and communication systems. It is time to move beyond case-specific solutions towards a more structured intergovernmental agreement (Wolff et al, 2025b). Alternative models exist, however. To credibly advance defence cooperation across a larger market, multiple issues around standards, procurement processes, export policies and state aid policies need to be agreed. For example, if a new weapon system is developed backed with state aid from several countries, a clear agreement needs to be in place ex ante on how restrictive export controls on that weapon would be applied, otherwise cooperation will be put into question.

Implementing these recommendations will not be easy as strategic cultures across Europe remain fragmented. We have, however, shown a substantial increase in deliveries to Europe of US weapons in the last four years. This grants leverage to US decision makers. A level-headed debate on what strategies are feasible to bolster European strategic autonomy is thus needed urgently. Policymakers should also take into account the upside of spending on European defence tech. Defence spending can stimulate long-term economic growth through its effect on R&D (Antolin-Diaz and Surico, 2025), but that impact is diminished when the spending is directed to imports rather than domestic products. The case for defence R&D is thus not only driven by security considerations (Steinberg and Wolff, 2023) but also by growth effects.

Ultimately, European policymakers must understand that they need to go beyond discussions of individual policy questions, such as whether to buy US or domestic air defence. Deeper structural issues need to be dealt with. Agreements need to be forged on command-and-control structures 39 and on deeper defence planning and procurement integration (Wolff et al, 2025b). Failing to make progress means accepting that Europe cannot remain a free and autonomous continent.

Source : Bruegel