Combining product and capital market reforms at EU level with labour market and social policies at national level would be desirable, particularly within the euro area. The Lisbon Agenda has failed to deliver this coordination. The best policy strategy would be for the EU to go back to basics and focus all efforts on completing the single market. At the same time, member states that require urgent reform of their labour and social policies must take internal action. Failing to do would not only run the risk that Europe misses the opportunities of globalisation, but could even be damaging to both the single market and monetary union.

1 European renewal

The Constitutional stalemate and failure to agree changes to the budget have spawned a new and open debate on the future of the European Union. In his speech to the European Parliament on 23 June 2005, incoming Council President Tony Blair said that he believed in Europe as a political project that offered its citizens strong social protection. But he also warned that Europe needed a “social Europe that worked”.

At the special summit in Hampton Court (held on 27 October 2005), Europe’s leaders will discuss how to maintain and strengthen social justice and competitiveness in the context of globalisation, a subject which is now more widely discussed than ever before – and not just by politicians.

In this Policy Brief I attempt to make three points which may shed some light on the current debate:

- The global economy of the twenty-first century is characterised by rapid changes, which create both threats and opportunities. To take advantage of the opportunities labour market and social policies that are stuck in the past must above all be reformed. Failure to reform will not preserve the status quo, but could even threaten both the single market and monetary union.

- The notion of a single ‘European social model’ is largely misleading. There are a number of different European social models with different performances in terms of efficiency and equity”. Models that are not efficient are by definition unsustainable and must be reformed.

- Labour market and social policy reforms are a matter for the member states alone, while other necessary structural reforms, such as the completion of the single market for services, are decided at the EU level. There are undeniable benefits to be had from coordinating action in a two-handed strategy, especially for countries in the euro area. This was precisely the purpose of the Lisbon Agenda, but it is rapidly failing. The priority at the EU level should now be geared to completing the single market.

2 Why reform?

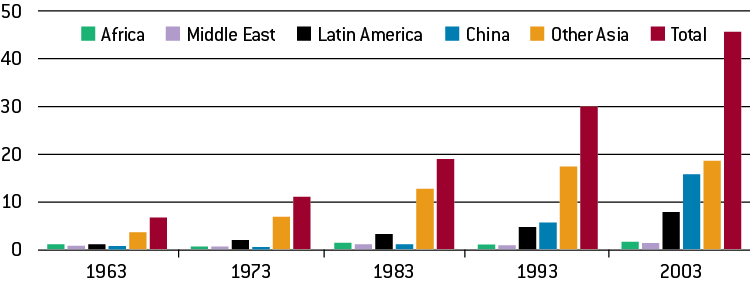

The engine of change that is both driving the need to reform, and threatening some of the past achievements of the European economic system, is fuelled by a heady mixture of technology and politics. The past 25 years have seen the world economy make rapid technological advances combined with political transformations such as the adoption of market capitalism by China, India and the former Soviet Bloc. One measure of the change in global trade patterns is the increase of the share of emerging economies in manufactured product markets long dominated by advanced country suppliers. As recently as 1970, the share of developing countries in developed countries imports of manufactured products was barely 10 percent.

Today, as Figure 1 shows, their share is over 45 percent.

Figure 1: share of developing countries in developed countries imports of manufactured products (%)

Source: Bruegel based on WTO data.

Most of this phenomenal rise comes from East Asia with China a late but fast expanding entrant. China has gone from a share of just 2 percent at the start of its economic transformation in 1985 to 15 percent today, and has overtaken Japan as the EU’s second largest supplier of manufactures and of goods in general. The emergence of developing countries as major suppliers of manufactured goods and services is only just starting. In particular, developing Asia, including India and China, is expected to continue growing steadily at more than 6 percent per annum for at least a generation.

This rapid change in the global economy creates both opportunities and threats. The opportunities will fall to those able to respond quickly with the right technology and skills. This will sometimes require the political courage to take action that hurts in the short-term, but pays off in the long run. The benefits associated with the opportunities take time to materialise, since they require investment in new activities; the costs associated with the threats are incurred more rapidly since they derive from what we are already doing. Postponing inevitable changes is not a desirable option as it would only delay the benefits and increase the costs.

The challenge to economic policy, therefore, is to conceive and implement, as soon as possible, economic and social reforms aimed at greater economic adaptability and better social protection.

3 The European status quo

In Europe, the needed reforms concern above all a range of increasingly dysfunctional labour market and social institutions established in the 1950s and 1960s when the economic environment was relatively stable and predictable. Instead of fostering the necessary adaptation and flexible responses to increasingly rapid changes, modern European welfare states, which had helped fuel economic and social progress during the ‘trente glorieuses’ (the 30 years between 1945 and 1975 when Europe witnessed an unprecedented period of growth, stability and social cohesion), now often protect the status quo.

As Nobel Prize winner James Heckman rightly stated in his insightful analysis of Europe, “The opportunity cost of security and preservation of the status quo – whether it is the status quo technology, the status quo trading partner, or the status quo job – has risen greatly in recent times” (Heckman, 2002).

During the past 25 years Europe has not remained idle. Indeed, recognition of the need to improve Europe’s economic performance in the face of globalisation has driven much of EU economic policy during the past two decades. But important European level institutional achievements such as the Single Market Programme, the sponsorship and support of R&D and monetary union have failed to generate greater economic dynamism.

Progress towards the completion of the single market is too slow; the EU budget remains a relic of the past, allocating far too much to agriculture and too little to research and innovation; and economic stability associated with monetary union has not yet succeeded in generating additional growth. In fact, according to most estimates, the EU’s potential growth is now only 2 percent a year compared with almost 3.5 percent in the United States and 4 percent for the entire world.

The simple but difficult choice facing European policymakers is not the black and white one of preserving the status quo versus abandoning the cherished European social model. It is instead a choice between reforming national labour market and social policies, or continuing to hinder change. In the first case, the two major economic achievements of the EU in the last decade, the single market and the euro, will be turned into building blocks towards making globalisation an opportunity. In the second case, not only will globalisation become a major threat, but both the single market and the currency union will increasingly be perceived as threats as well.

Consider first the single market. Transforming the enlarged European Union of 27+ members into a genuine single market, in which goods, services, capital and labour are allowed to circulate freely, would offer great opportunities to old and new member states alike. But this rosy scenario – endorsed by European elites – in which everyone gains can only materialise if national labour market and social policies become more conducive to changes in specialisation. This is especially true in ‘Old Europe’, where those losing their jobs in old activities often find it difficult to obtain employment elsewhere. There, citizens often tend to view enlargement as a zero-sum game, where the gains for new member states come at the expense of the old ones.

The pan-European industrial reorganisation needed to take advantage of the opportunities coming from enlargement is too often seen by the public as a burden coming on top of the weight of global competition. This perceived burden, which not only increases the threat of delocalisation and competition from imports, also raises the spectre of immigration, as seen in fears about ‘Polish plumbers’. Since enlargement is now a reality, the backlash comes in terms of opposition to the single market itself. As the debate over the Services Directive, proposed by the European Commission in January 2004, has shown, by greatly increasing economic and social disparities and the pressure to restructure inside the EU, enlargement has certainly complicated the goal of completing the single market. Yet, the single market not only constitutes the keystone of European integration, but also remains the most potent European instrument to address the challenge of globalisation.

Dysfunctional labour market and social policies are not only a threat to the single market, but also endanger the currency union. Any European country is bound to suffer from structural changes if its markets are inflexible and do not allow the necessary transfer of resources across firms, sectors or regions. For members of the euro area, market-led flexibility is even more important as those countries share a common monetary policy, which precludes the use of the exchange rate as an instrument of change – albeit an inadequate one.

The lack of appropriate market mechanisms is bound to lead to attempts to use fiscal policy as a temporary remedy. However, such attempts would not only conflict with the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), but could even threaten its survival. This threat could come either from countries adopting unsustainable fiscal positions, or from public discontent over the currency union itself as a result of unpopular measures taken to respect the SGP.

Although the demise of the euro area or the exit of some of its members is certainly not as close as some proclaim, the debate will continue to surface as long as members remain plagued by inflexible markets – particularly labour markets – that prevent them from making the necessary economic adjustments.

4 The four European social models

Although they all share certain common values, there are so many differences between national welfare state systems that the very notions of a ‘European Model’ or ‘Social Europe’ are rather dubious, at least for analytical purposes. I prefer to use the now familiar grouping of national systems into four different social policy models in order to examine their relative performances along a number of dimensions.

Nordic countries feature the highest levels of social protection expenditures and universal welfare provision. There is extensive fiscal intervention in labour markets, and strong labour unions ensure highly compressed wage structures.

Anglo-Saxon countries (Ireland and the United Kingdom) feature relatively large social assistance of the last resort. Cash transfers are primarily oriented to people in working age. Active measures to help the unemployed get jobs, and schemes that link access to benefits to regular employment are important. This model is characterised by a mixture of weak unions, comparatively high disparities in wages and a relatively high incidence of low pay.

Continental countries rely extensively on insurance-based benefits and old-age pensions. Although union membership is in decline, the unions remain strong.

Finally, Mediterranean countries concentrate their social spending on old-age pensions – though there are wide differences in both the degree of entitlement and the amounts received. The social welfare systems typically draw on employment protection and early retirement provisions, and in the formal sector, the wage structure is covered by collective bargaining and is highly compressed.

Protection against uninsurable labour market risk can either be provided by employment protection legislation (EPL), which protects workers against firing, or by unemployment benefits (UB) (Boeri, 2002). The differences between the two systems are clear: legislation protects those who already have jobs and does not impose any tax burden, whereas benefits provide insurance to the population at large and are typically financed by a tax on those who work. Since the two instruments are designed to achieve a similar purpose there is a clear trade-off between them. Having a generous unemployment insurance system reduces the need for restrictions against getting fired, and vice versa.

The four European social policy models behave very differently. The Mediterranean model has generally strict employment protection legislation (at least for permanent workers) and a rather low coverage of unemployment benefits. In contrast, the Nordic model provides unemployment benefits that are generous and comprehensive, but the strictness of their EPL is quite low. The Continental model also provides generous unemployment benefits, but its EPL is stricter. Finally, the Anglo-Saxon model has comparatively less employment protection legislation but as much unemployment insurance as the Continental and Nordic models.

Rewards for labour market participation vary a great deal across the four models. Employment rates are far higher in Nordic and Anglo-Saxon countries (respectively 72 percent and 69 percent in 2004) than in Continental and Mediterranean countries (respectively 63 percent and 62 percent), with much of the difference attributable to the two ends of the age spectrum. The Nordics and Anglo-Saxons are more successful in keeping the employment rate for older workers high and the unemployment rate for young workers low.

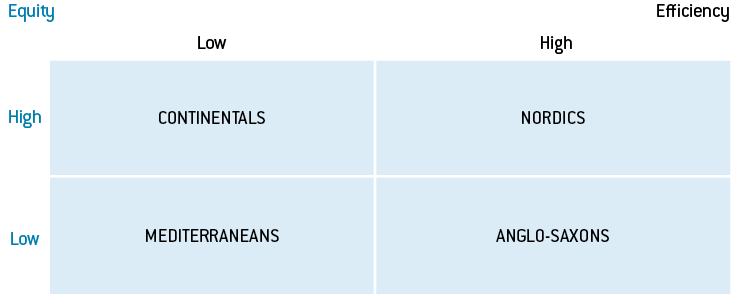

This comparative analysis of the four models can usefully be summarised using two criteria: ‘efficiency’ and ‘equity’. For illustrative purposes a model will be considered efficient if it provides sufficient incentive to work, therefore generating relatively high employment rates. It will be deemed equitable if it keeps the risk of poverty relatively low. Figure 2 plots the probability of escaping poverty against the employment rate for the four country groupings and each of the 15 pre-2004 EU members.

Figure 2: employment rates and probability of escaping poverty

Source: Bruegel.

There is a strong connection between the employment rate generated by a social system and the instrument it uses to protect workers from the vagaries of the labour market. The stricter the employment protection legislation of a model, the lower its employment rate. By contrast, the generosity of unemployment benefits only plays a secondary role. This means that protecting jobs with employment legislation is definitely detrimental to employment, whereas protecting workers with unemployment insurance is potentially useful for employment.

All Nordic and Continental countries rank above average in terms of the probability of avoiding poverty, while all Anglo-Saxon and Mediterranean countries rank below average. What accounts for this difference? The extent of redistribution via taxes and transfers is important, but it cannot be the major explanatory factor. A better explanation is the difference in the distribution of human capital. The proportion of the population aged 25-64 with at least upper secondary education is highest in Nordic (75 percent) and Continental (67 percent) countries, and lowest in Anglo-Saxon (60 percent) and Mediterranean (39 percent) countries – a ranking that perfectly matches the position of country groups in terms of poverty risk.

Figure 3 compares the four models in terms of efficiency and equity. This typology is the product of the illustrative definition of ‘efficiency’ and ‘equity’ chosen here. Different definitions might affect somewhat the exact allocation of individual countries but the typology itself would broadly remain.

Figure 3: the four European models, a typology

Source: Bruegel.

Examination of these models prompts the following conclusions:

- The Mediterranean model, characterised by relatively low levels of employment and a high risk of poverty, provides neither equity nor efficiency.

- With the Anglo-Saxon and Continental models there appears to be a trade-off between equity and efficiency.

- Only the Nordic model, with high employment rates, and a low risk of poverty combines both equity and efficiency.

Obviously, equity has a price and tends to be higher, therefore, in countries with relatively higher levels of taxation. By contrast, efficiency appears not to be related to levels of taxation. What is perhaps the most striking is the comparison of models with the same level of equity but different levels of efficiency. The Nordic model combines higher taxation (51 percent of GDP in 2004, including social contributions) and higher efficiency than the Continental model (46 percent), while the Anglo-Saxon model combines lower taxation (36 percent) and higher efficiency than the Mediterranean model (42 percent).

Another reading of Figure 3 emphasises the sustainability of social models. Models that are not efficient, and have the wrong incentives to work, are simply not sustainable in the face of growing strains on public finances coming from globalisation, technological change and population ageing. On the other hand, models that are not equitable may be sustainable.

In the current historical phase, the case for reform is therefore strongest in the Continental and Mediterranean countries, where the welfare state has become highly inefficient. Their reliance on strict employment protection laws it discourages adaptation to change and preserves the status quo. The system therefore reduces overall employment and raises unemployment. For a long time ‘median voters’ were largely spared from growing unemployment – the burden falling mainly on the young and immigrants, while older workers exited the labour market mainly through generous early retirement schemes. Today, however, the political equilibrium has changed. Median voters are no longer insulated from the ever-growing pressure of globalisation and also realise that the combination of population ageing and low employment rates jeopardises their future pension benefits.

There is no reason a priori to assume that such reform must go hand in hand with changes in terms of equity. It is perfectly possible for the Continental model to become more like the Nordic one and for the Mediterranean model to become more like the Anglo-Saxon model. Nonetheless, one cannot reject the possibility that a reform towards greater efficiency may also unleash a change towards more or less equity.

The message, however, is not that the Continental and Mediterranean models are going to disappear and that only the Nordic and Anglo-Saxon models will survive. It is simply that the former must reform in order to become more efficient, probably by adopting some features of the latter.

Reforms of the Continental and Mediterranean countries are crucial not only for themselves. The reason is simple arithmetic – their combined GDP accounts for two thirds that of the entire EU25 and 90 percent of the 12-member euro area. The economic and social health of these countries is therefore of paramount importance for the smooth functioning of the entire European Union and of the euro area.

5 Policy challenges

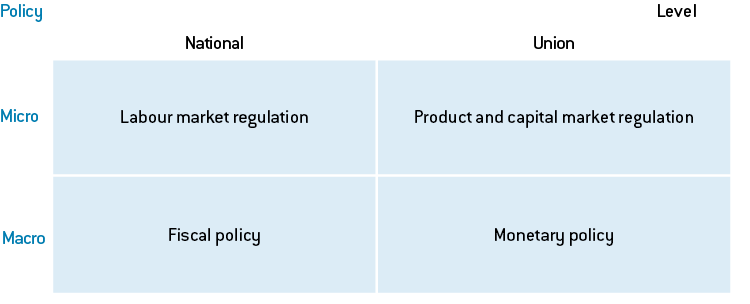

Since countries with inadequate labour market and social policies account for such a large proportion of EU and euro-area GDP, the question arises as to what can and should ‘Europe’ do to help promote the necessary reforms. As shown in Figure 4, in the microeconomic sphere, labour market regulation is largely decided at national level, whereas the EU level deals mostly with product and capital market regulation. In the macroeconomic sphere, the member states are responsible for fiscal policy, but monetary policy for the euro area is managed by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Figure 4: Assignment of economic policies in the EU system

Source: Hagen and Pisani-Ferry (2002), but originally suggested by Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa.

The question about the potential role of Europe in the process of reforming national labour markets raises several questions about coordination:

- Should labour market reforms among EU countries be coordinated?

- Is there a case for coordinating labour market reforms with reforms of product and capital market regulation?

- For euro-area countries, is there a case for coordinating structural reform and macroeconomic policy?

Despite commitments to coordinate employment policies at the European level, the fact of the matter is, labour market and social reforms need to be conceived and engineered by each member state according to its own economic, social and political reality. To the extent that it clearly and solely focuses on benchmarking and exchange of best practices, coordination can be useful. Beyond that, coordination of labour market and social policies is probably an obstacle rather than a catalyst for reform, because it tends to blur the responsibility between national and EU authorities.

Placing responsibility where power lies is crucial for good functioning of the EU system. The failure to do so has resulted in the public becoming utterly confused about who is responsible for what – a sure recipe for voter dissatisfaction. This is not to deny however that some labour market and social policies (such as those concerning migration) must be handled at the EU level.

So far, the concentration in this Policy Brief has been solely on labour market reforms. Yet it is well known that the structure of product and capital markets affects the performance of the labour market and vice versa. Reforms of product and capital markets tend to increase the demand for labour and thereby ease the pain of labour market reforms. Reforms of labour markets encourage new firms, thereby assisting reforms of product and capital markets. For an individual country to take advantage of this potentially virtuous circle makes economic sense. But the positive effect of such coordination would be strengthened still further if member states, who share the single market, were to coordinate reforms.

There are two ways of solving the chicken-and-egg problem between product and capital market reforms at the EU level on the one hand, and reforms in national labour markets on the other. One is to concentrate all energy on the EU level, secure product market and capital market liberalisation, and hope that this will eventually trigger labour market reforms through some ‘TINA’ (there is no alternative) process. The other is to act simultaneously at both levels. The advantage of the second solution is that it would, in principle, be more efficient and less painful, as labour market reforms would benefit from product and capital market reforms, and vice versa. The Lisbon Agenda can be viewed as an attempt to solve this ‘coordination failure’ between EU and national reforms. Unfortunately, Lisbon has not delivered.

The lack of interest displayed by EU countries in coordinating their structural reforms via the Lisbon process may be due to uncertainty concerning the extent of the spillover benefits generated by reforms in other member states, as a result of the single market. There is, however, a subset of EU countries for which spillovers, and therefore the case for coordination, are undeniable. To the extent that structural reforms in one euro-area country affect the average inflation rate of the zone, there is a case for coordinating structural reforms since they affect the common interest rate.

The case for coordination is especially important when it comes to implementing reforms that are costly in the short term12. Labour market reforms may increase unemployment before they lower it, because they create anxiety and lead firms to shed redundant labour faster than they create new jobs. Product market reforms may also depress growth because the losses by incumbents are immediate while new entities take time to develop and grow. This is why reform is easier when accompanied by monetary expansion and fiscal relaxation.

For understandable reasons the ECB is unwilling to engage in formal coordination with governments and to cut interest rates ahead of structural reforms. Members of the euro area, therefore, need to act first. Coordinated structural reform by the main players in the euro area would be a powerful signal to the ECB. It is also essential for the countries of the euro area, where progress with structural reform has been particularly slow.

Summing up, Europe cannot and should not have a strategy for reforming national labour market and social policies. It is up to each national government to devise its own strategy.

Yet, a two-handed approach, combining product and capital market reform at the EU level with labour market and social policy reform at the national level would be superior to a strategy seeking to reform national labour and social policies alone, especially for the countries in the euro area.

The Lisbon Strategy was an attempt to implement this kind of two-handed approach, but the Lisbon method was simply too weak to deliver. Five years after its launch in 2000, it has delivered neither a major thrust towards completing the single market nor significant labour market reforms.

6 What should be done?

At this stage, the best strategy would be to go back to basics and focus all efforts at the EU level on completing the single market.

The single market and an active competition policy are the cornerstone of efforts at the EU level to improve the functioning of markets, and thereby, Europe’s capability to respond to the challenges of globalisation and technological change.

By removing barriers to the mobility of products and capital and by fostering competition, the Single Market Programme (SMP) was expected to raise EU productivity, employment and growth. Yet, growth has been mediocre, with Europe’s performance deteriorating both absolutely and compared to the United States during the past 20 years since the launch of the SMP. Besides German reunification and other shocks, there are three main reasons for this.

- The SMP was never fully implemented. Since 1993, the single market has been a reality for goods, but service markets, including financial markets, remain highly fragmented. Yet the efficient provision of services – which account for about 70 percent of European economic activity and offer the greatest opportunities for employment growth – is crucial for a modern economy.

- The conception and implementation of the SMP were rooted in yesterday’s thinking. They were based on the assumption that Europe’s fundamental problem was the absence of a large internal market that would allow companies to achieve big economies of scale. It has now become clear that the problem lay elsewhere. In the modern world, what European industry needs is more opportunity to enter new markets, more retraining of labour, greater reliance on market financing and higher investment in both research and development and higher education.

- The SMP naturally excluded the liberalisation of labour markets, since this falls within the competence of the member states. Yet, without such reform and greater labour mobility within and across companies, the liberalisation of markets was unlikely to trigger the reallocation of resources necessary to produce higher growth.

Following the rejection in March 2005 by the European Council of the Services Directive tabled by the Commission in January, the creation of a single market for services – a crucial component of the Lisbon Agenda – remains uncertain at best.

This lack of progress on services is bad news for the competitiveness of the European manufacturing sector, which is more and more intertwined with the provision of modern and flexible services. Additionally, as the discussion about the ‘Polish plumber’ demonstrates, the stalling of progress on services illustrates the fundamental tension between the goals of creating a genuine single market among 27+ countries with vast economic and social disparities, while at the same time preserving the European social model.

It is not the single market that threatens the European social model, but the inability to reform that model, or some of its incarnations, in the face of rapid global changes. With or without the Services Directive, the rise of manufacturing in China and the exodus of back-office services to India are inevitable. With or without it, the addition of 12 new member states is bound to affect the services market, either in the open or in the shadows.

Completing the integration of the 27-plus economies of the European Union must be the utmost priority of efforts at EU level to revitalise the European economy. But member states must also carry out parallel reforms of national labour market and social policies that are geared towards improving the capacity of their economies and citizens.

Poised at this new crossroads in Europe’s economic history, policymakers must choose the path of reform at both EU and national levels. Only then will it be possible to reap the opportunities offered by globalisation and technological change, and fulfil the promise of the single market and monetary union.

Europe’s labour and social institutions need urgent reform in order to grasp the opportunities offered by globalisation and avoid the threats. But the notion of a single ‘European social model’ is largely unhelpful for thinking about reforms. Of the four main models operating in Europe, the ‘Nordic’ and ‘Anglo-Saxon’ models are both efficient, but only the former manages to combine both equity and efficiency. Critically, the ‘Continental’ and ‘Mediterranean’ models, are inefficient and unsustainable. These models must therefore be reformed, probably by adopting features of the two more efficient models. These reforms may also involve changes towards more or less equity.

Source : VOXeu