Executive summary

In an environment of record-breaking electricity prices driven by a gas supply shock and below-average electricity generation, reforming the design of the European electricity market is seen as a means to delink consumer costs from volatility in short-term power markets.

Electricity markets should meet three objectives: fairness, optimal investment and optimal operation. The current market design has achieved these objectives to varying degrees. Faced with the unprecedented shock, the electricity system has operated well, but electricity markets have struggled to achieve fair outcomes and investments have not been driven by market-based cashflows.

Further complicating market reform, the power system is being changed radically by decarbonisation. The electricity system is becoming more decentralised and digitalised, with an active demand side. These transformations will have consequences for the optimal electricity market design in the later stages of the energy transition.

Reform proposals have focused on increasing the share of long-term contracts in the remuneration of generation technologies. Different long-term contracting regimes have structural implications for the functioning of electricity markets, especially in relation to the roles of the state and the market, and the responsibilities of national governments and European Union institutions.

A phased approach should be taken to EU electricity market design reform. In the near-term, reform should seek to protect consumers and drive investment. An assessment should also be made of what market design will best meet the fairness, investment and operational objectives in a decarbonised system, and what the conceptual role of electricity markets should be during the transition. This process should start as soon as possible so well thought-through proposals are available when the next European Commission takes office.

1 Introduction

Electricity market design is a central political issue in 2023. Electricity consumers face record energy costs, and the European Union has promised to address these through market design changes. A plan to reform the EU’s electricity market design was published on 14 March 2023 (European Commission, 2023).

More structurally, electricity market design is one of the EU’s main instruments for an efficient transition to a climate-neutral energy system, reliant on clean electricity. Properly designed electricity markets can incentivise the deployment of clean-energy technologies, including renewable generation capacity, and the flexible assets needed to support them, thereby maintaining security of supply. Market design can also help ensure the efficient and safe operation of the electricity system, which will increasingly become the backbone of decarbonised economies. In addition, electricity markets can help to distribute the costs and benefits of the electricity system fairly.

In this paper, we set out a framework for evaluating the many interrelated issues in the current EU electricity market reform discussion, including the objectives that should be defined for electricity markets and the implications of certain reform ideas. We propose a phased reform process that can meet the near-term needs while preparing the EU electricity market for the system of the future. We start by discussing key conceptual choices when designing electricity markets, the issues electricity market design should address and the link between gas and power prices. We then review the market reform debate (section 2), propose three objectives for electricity markets (section 3), discuss key aspects of power system transformation (section 4) and assess how these transformations affect the market objectives (section 5). The broader implications of the reform proposals are then discussed in section 6. Section 7 sets out our proposal for phased reforms.

1.1 Key conceptual choices

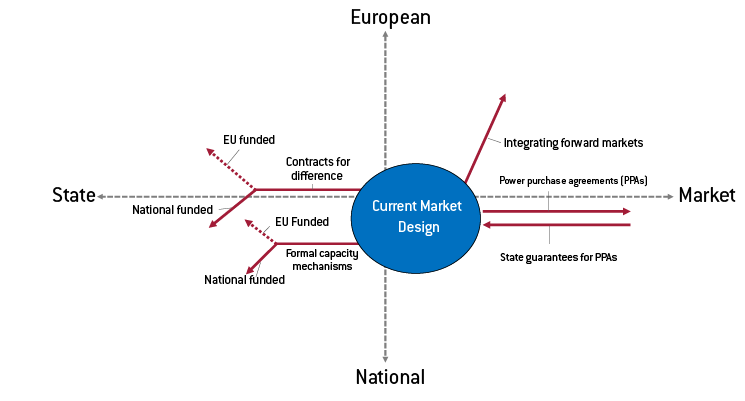

Fundamental questions for electricity market design, especially as the energy transition accelerates, include the optimal balance between state-led planning and market incentives, the extent to which the state should take on investment risk, the relative role of European and national decisions as well as the choice between more decentral bilateral exchanges versus more central clearing. The proposed instruments would likely shift the current balance (Figure 1). But these conceptual implications for the European electricity sector are currently not part of the conversation, indicating a risk of dilution of responsibilities.

Figure 1: Implied conceptual choices of reform proposals

To avoid a scenario in which Europe takes fundamental decisions for the future of its electricity system with inadequate understanding of the consequences, we argue that the conceptual implications of each reform proposal should be discussed explicitly at this critical juncture. A long-term reform process should also be initiated to give enough time for deep assessment of the optimal role of electricity markets during the energy transition.

1.2 What problem does electricity market reform address?

The reform debate is taking place at a time of record high consumer electricity prices in Europe. Meanwhile, many utilities are earning record revenues and profits (Figure 2). Given this situation, the reform priority for many stakeholders is fairness.

Figure 2: Domestic electricity prices and European utility revenues, H1 2021 vs. H1 2022

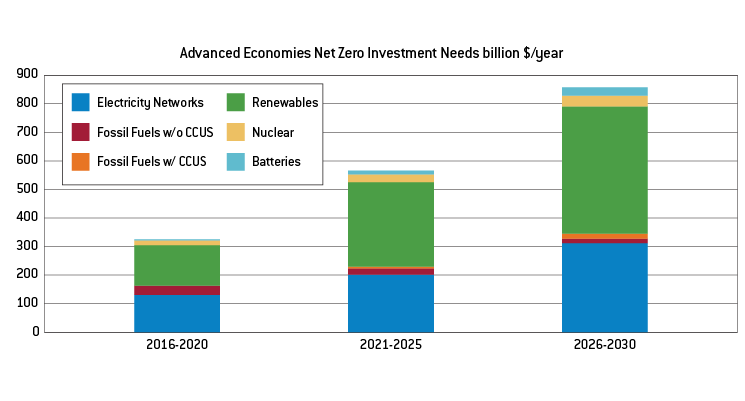

Another vital aim for electricity markets is to send clear investment signals in relation to the technologies needed to decarbonise the power system. Measures that could reduce consumer costs in the short-term could also hold back the energy transition. The electricity market and its associated institutions must therefore provide clarity and certainty for investors, while also ensuring fair outcomes. To reach net zero, the scale of investment in Europe and across the globe will need to drastically ramp up in the coming years (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Investment needs to meet net-zero

Wholesale market design is only one lever to shape fairness and efficiency in the electricity sector. The ultimate financial flows between electricity market participants depend strongly on the multiple wholesale market segments, and also on the regulation of network access and remuneration, retail market design, and taxes, levies and subsidies. In line with the ongoing debate, we focus primarily on the wholesale market but also discuss retail markets and other aspects.

1.3 The link between gas and power

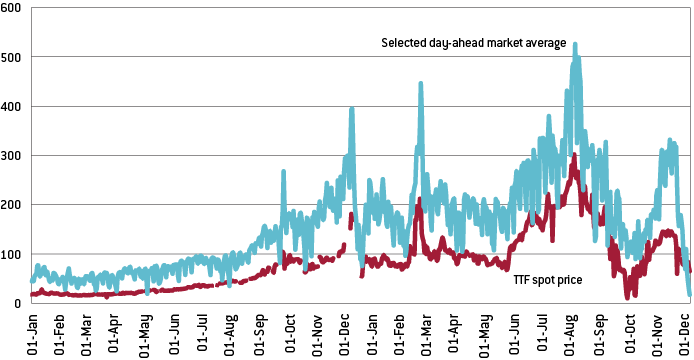

At the root of the energy crisis is a gas-supply crisis. Faced with huge cuts to pipeline gas from Russia, European countries have been forced to purchase their gas supplies on international liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets at a significant premium. Because of the European electricity generation mix and the pricing mechanism in electricity spot markets, these gas-price increases have translated into electricity price spikes. Figure 4 shows the spot price at the Title Transfer Facility (TTF), Europe’s major gas trading hub, in 2021 and 2022, and an average of the Dutch, French, German, Spanish and Polish day-ahead market prices over the same period. The link between gas and power is clear[1].

Figure 4: 2021 and 2022 TTF spot price and day-ahead market prices

The link arises firstly and most importantly because gas-fired power generation makes up a large proportion of European electricity production (20 percent in 2022, surpassed only by nuclear, although the share of gas is projected to fall; Ember, 2023). Gas provides crucial flexibility to meet peak electricity demand, especially during periods of low wind and solar availability. As the cost of gas has increased, so has the cost of electricity generated with this fuel.

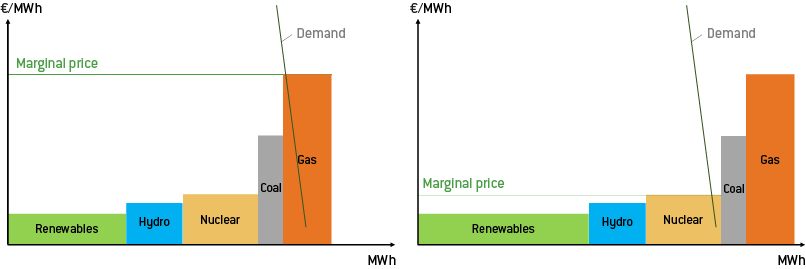

Secondly, European spot markets prices are determined according to the so-called merit order model (Figure 5, left panel). The price of electricity in a given time period is determined by the marginal cost of the most expensive generator needed to meet the demand in that period. This approach minimises the cost of supplying electricity to meet a certain level of demand, as it ensures the least expensive generators are used. However, since gas-fired generation is in many hours the so-called marginal generator (ie the most expensive generator), the cost of gas often determines the marginal electricity price. As gas plants require about two megawatt hours of gas to produce one megawatt hour of electricity. the marginal cost of one megawatt hour of electricity produced by gas is about twice as high as the price of one megawatt hour of gas (plus the carbon cost). This drives the correlation between gas and electricity seen in Figure 4.

However, the electricity price is not dependent on the gas price by definition, as the correlation only arises when gas is the marginal generator.

If the electricity-generation mix is changed by adding more renewables, run-of-river hydropower or nuclear (so-called ‘inframarginal’ generators), gas generation is pushed out of the merit order (Figure 5, right panel). The marginal price is set by gas generation in fewer periods as the share of generation from other sources increases. The implication is that by increasing investments in low variable cost generation and sufficient storage, and by enabling consumers to shift demand, the link between gas and power can be decoupled, without necessarily making changes to the market design.

Some countries (Greece, Spain) and even the president of the European Commission[3] in 2022 have advocated structural interventions to decouple prices from marginal cost, but the debate in early 2023 seems to accept that interventions (such as applying average prices for market clearing, subsidising marginal technologies or creating technology-specific markets with different prices) would need to be extremely carefully designed to limit the negative impact on the efficiency of market outcomes. For some discussion of the options see Heussaff et al (2022).

Figure 5: Stylised merit-order model with different renewables shares

2 What has been proposed?

2.1 Categorisation of reform proposals

The debate on electricity market reform includes some long-considered ideas and some new ideas, broadly categorised as follows.

Encourage long-term contracts

Many reform proposals focus on increasing the share of various types of long-term contracts, in order to delink the price received by electricity producers from spot markets.

The forward market could be improved. At present, there is limited trading beyond short time horizons, making it hard for participants to hedge. Improvements could be made by providing standardised, longer contracts and driving additional liquidity onto platforms, for example by facilitating improved coupling across borders in forward markets (Meeus et al, 2022). Removing barriers to more bilateral contacts between generators and consumers is suggested as a means to allow market participants to hedge their positions sufficiently.

Expanding and improving state-backed contracts for difference (CfDs, see section 6), tendered via competitive auctions, is advocated by several European countries, including France and Spain. There are several options for applying such schemes, either by making them optional for new projects, mandatory for all new developments, or even requiring all existing and new projects to sign a CfD.

Capacity mechanisms are a means to support the reserve capacity needed to meet peak demand. Such capacity is often only needed for short periods and cannot recover its costs from the spot markets. At present, state-aid approval is required to implement such mechanisms because of the risk that they could be used uncompetitively to support unviable technologies. Spain and Poland have called for formal recognition of the need for capacity mechanisms (see Annex 2).

Adjust pricing mechanisms

Another proposed means to decouple the consumer price of electricity from short-term volatility is to alter the pricing mechanism in the wholesale markets. Variations of this approach were approved as emergency measures in 2022 under Article 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

The first of these emergency measures is the so-called Iberian mechanism, a joint scheme applied in Spain and Portugal that subsidises the fuel costs of gas and coal powerplants to insulate the electricity markets from exceptional gas prices. The Iberian countries have requested an extension to the measure and Portugal has proposed pan-EU implementation of a similar ‘emergency clause’ that would set an upper limit on spot market prices in certain circumstances (see Annex 2).

Another emergency measure is the inframarginal revenue cap, approved by the Commission for implementation at member-state discretion (Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1854). The revenue cap does not directly change the spot market price but instead limits the revenues that technologies with low variable cost can earn from the market.

Other changes to the pricing mechanism include remunerating generators on the spot market based on their individual bids, rather than the clearing price (the price of the most expensive generator), or paying generators the average of the marginal cost of all generators. However, the consensus is that such approaches would create incentives for inefficient behaviour and are therefore not under consideration.

Source : Bruegel