Internal balance-of-payment crises should be taken as a strong signal of weakness and a wake-up call to reform euro area structures

The single currency was expected to make the balance of payments irrelevant between the euro-area member states. This benign view has been challenged by recent developments, especially as imbalances between euro-area central banks have widened within the TARGET2 settlement system.

Current-account developments can be misleading as indicators of financial account developments in countries that receive significant official support. Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain experienced significant private-capital inflows from 2002 to 2007-09, followed by unambiguously massive outflows.

We show that such reversals qualify as ‘sudden stops’. Euro-area sudden-stop episodes were clustered in three periods: the global financial crisis, a period following the agreement of the Greek programme and summer 2011. The timeline suggests contagion effects were present.

We find evidence of substitution of the private capital flows with public components. In particular, weak banks in distressed countries took up a major share of central bank refinancing. The steady divergence of intra-Eurosystem net balances mirrors this.

In the short term, TARGET2 imbalances could be addressed by tightening collateral requirements for central bank liquidity. For the longer term, the evidence that the euro area has been subject to internal balance-of-payment crises should be taken as a strong signal of weakness and as an invitation to reform its structures.

1 Introduction

There is a view that the euro crisis is a balance-of-payments crisis at least as much as a fiscal crisis1. This claim could have a bearing on the nature of the policy response, which thus far has concentrated on strengthening budgetary discipline and has treated external imbalances as a second-order matter.

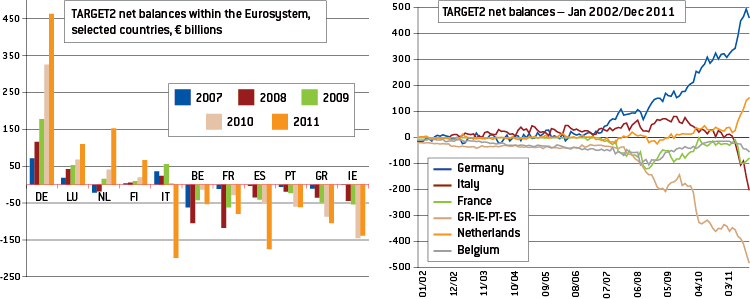

The issue has become more relevant with the widening of imbalances between euro-area central banks within the TARGET2 settlement system – the Eurosystem’s interbank payment system2. The cumulated net position of the northern euro-area central banks reached €800 billion in December 2011, being matched by the southern euro-area central banks’ equivalent negative position.

The balance-of-payments discussion lacks clarity, however. First, it seems awkward to speak of balance-of-payments crises within a monetary union that was designed to make such crises impossible. Second, few of the proponents of the balance-of-payments crisis view have substantiated their claims with clear evidence. Unlike a standard balance-of-payments crisis, within the euro area, current-account deficits have adjusted partially and slowly. Third, the relationship between TARGET2 balances and balance-of payment imbalances remains confused.

The purpose of this paper is to fill these gaps. We start in section 2 with a brief discussion of the possibility of a balance-of-payment crisis within a monetary union and an overview of the evolution of current-account balances. In section 3 we analyse the evolution of private capital flows to southern Europe before and during the euro crisis. In section 4 we proceed to a more formal test and apply standard sudden-stop criteria to the evolution of capital flows. In section 5 we discuss the roles played by central banks and official financing. We return to policy issues in section 6 to discuss the consequences of our findings.

2 Crisis? What crisis?

In one of the earliest papers on European monetary union, Ingram (1973) noted that in such a union “payments imbalances among member nations can be financed in the short run through the financial markets, without need for interventions by a monetary authority. Intracommunity payments become analogous to interregional payments within a single country”. This view was not challenged in the debate of the 1980s and the 1990s on the economics of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). It quickly became conventional wisdom. The European Commission’s One Market, One Money report (European Commission, 1990) similarly posited that “a major effect of EMU is that balance-of-payments constraints will disappear […]. Private markets will finance all viable borrowers, and savings and investment balances will no longer be constraints at the national level”. The important words here are “all viable borrowers”, meaning that the budget constraint applies to individual borrowers, not to countries as such. In other words, a solvent company in Italy or a solvent bank in Spain cannot be cut off from market financing because of the situation of the sovereign or the households. There is no such thing as a specific country-level intertemporal budget constraint – only those of individual agents matter.

This view was so widespread in the early 1990s that the Maastricht negotiators decided to exclude members of the common currency from the benefit of EU balance-of-payments assistance under Article 143 of the Treaty – with the result that the euro area was left without an instrument to provide assistance to Greece and had to rely in a first step on bilateral loans from its member countries, before the European Financial Stability Facility and the European Stability Mechanism were created. As reported in Marzinotto et al (2010), this exclusion had nothing to do with the no-bail-out clause. It was simply assumed that balance-of-payment crises within the euro area would become as unthinkable as they are within countries3.

To our knowledge, the only one to challenge this benign view was Peter Garber in a 1998 paper on the role of TARGET in a crisis of monetary union (Garber, 1998). The paper insightfully recognised that the federal structure of the Eurosystem and the corresponding continued existence of national central banks with separate individual balance sheets made it possible to imagine a speculative attack within monetary union. According to Garber, the precondition for an attack “must be scepticism that a strong currency national central bank will provide through TARGET unlimited credit in euros to the weak national central banks”. His conclusion was that “as long as some doubt remains about the permanence of Stage III exchange rates, the existence of the currently proposed structure of the ECB and TARGET does not create additional security against the possibility of an attack. Quite the contrary, it creates a perfect mechanism to make an explosive attack on the system”.

As said, the benign view prevailed during the first ten years of EMU. It even continues to dominate today. Indeed, casual data observation seems to vindicate it. Figure 1 reports the 2007-11 evolution of current-account balances in the three non-euro area EU countries and the three euro-area countries with the highest deficits in 20074. It is apparent that the two groups of countries have not followed the same path: whereas adjustment has been brutal for the first group, with deficits amounting to 15 to 25 percent of GDP transformed into surpluses over three or four years, it has been very slow for the second. One may even wonder if Greece and Portugal have adjusted at all.

Figure 1: A tale of two adjustments: current accounts outside and within the euro area

Source: ECFIN Forecasts November 2011.

3 Private capital flows

Assessing if there has been a balance-of-payment crisis by looking at the evolution of the current account is however a flawed approach. It is adequate to look at the evolution of current account balances as long as it offers a mirror image of net private capital flows. In a stand-alone country, this is largely the case except for foreign exchange interventions by the central bank – at least as long as the country is not under an International Monetary Fund programme. This is however not the case for monetary union, because the financial account includes official capital flows.

The correct accounting identity (neglecting the balance of the capital account as well as errors and omissions) is:

(1) CAB + PCI + T2F + PGM +SMP = 0

in which CAB stands for the current-account balance, PCI for private capital inflows, T2F for Eurosystem financing through the TARGET2 system (change in the net liability of the national central bank vis-à-vis the rest of the Eurosystem), PGM for financing through official IMF and European assistance, and SMP (Securities Markets Programme) for European Central Bank purchases of government securities from residents. Of these five flows, four are recorded statistically and only one (SMP) is not known.

In what follows we evaluate private capital inflows to southern Europe from 2002-11 using monthly financial account data. Capital flows are taken from national balance-of-payments as published by national central banks, and we deduct from them official inflows resulting from changes in TARGET2 balances (see Box 1) and assistance under IMF/EU programmes (see Appendices 1 and 2 for details).

Box 1: TARGET2

TARGET2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross settlement Express Transfer) is the Eurosystem’s operational tool through which national central banks of member states provide payment and settlement services for intra-euro area transactions. Intra-Eurosystem claims arise from different types of transactions and they can or cannot have a ‘real’ counterpart: they might be the result of transfers of goods that require a cross-border payment (ie imports) or the transfer of deposits to a different euro-area country. When capital is transferred (eg a deposit is moved) from an Irish bank to a German bank via TARGET2, the transaction is settled between the Irish central bank and the Bundesbank, with the former incurring a liability to the latter.

TARGET2 can be used for all credit transfers in euro and it processes both interbank and customer payments. There are transactions for which TARGET2 must be used5, but for all other payments – interbank and commercial payments in euro – market participants are free to use TARGET2 or any other payment system of their choice. Banks prefer the TARGET2 system because most banks in Europe are reachable through it and payments are settled immediately (immediate finality of the transaction) and in central bank money (allowing credit institutions to transfer money held in accounts with the central bank among themselves) (Kokkola, 2010).

The settlement of intra-Eurosystem payments via TARGET2 gives rise to cross-border obligations that are aggregated and netted out at the end of each single business day, leaving national central banks with a certain net TARGET2 balance (positive, negative or zero). There is no a priori limit to the transactions that can be processed by the system – and therefore to the size of TARGET positions. Daily net balances are generally remunerated at the respective interest rate for main refinancing operations (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2011a).

TARGET2 balances are balances that each central bank accumulates from the operations conducted vis-à-vis other national central banks in the euro area, but the final balance is a claim or a liability against the ECB, the ultimate manager of liquidity. In a way, it is as if the ECB were intermediating all transactions among national central banks6.

Until 2007, TARGET2 positions remained close to balance. From 2007 (and more so with the intensifying of the sovereign debt crisis in 2010) the balances started to diverge, with Germany becoming the largest creditor and Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal being traditional net borrowers and Italy moving into a negative position during the summer of 2011. The huge increase in TARGET2 claims and liabilities has recently drawn attention, triggering a debate on the forces behind this steady divergence (see Sinn and Wollmerhaeuser, 2011a; Buiter et al, 2011; Bindseil and Koenig, 2012; and Bornhorst and Mody, 2012).

Figure B1: TARGET2 balances in the euro area

Source: Bruegel, national central banks.

The build-up of such imbalances presupposes that capital does not flow uniformly across countries, meaning that central banks that report a deficit position have been systematically settling more outward payments than inward payments. In other words, some countries have been constantly net borrowers and other countries have been net lenders. This development is closely related to the tensions on the interbank markets and the increase in the perceived country risk in southern Europe. While payments between credit institutions can or cannot be processed via TARGET2, the transfers related to the Eurosystem monetary policy operations are managed through the system, so when the use of central bank liquidity becomes unevenly distributed across countries, TARGET2 balances will reflect it.

The steep increase in TARGET2 claims and liabilities from 2008 onwards suggests that tensions in the financial system may have an important role in explaining the divergence. In a period of financial crisis, banks in countries undergoing net payment outflows (eg deposit flights) need liquidity but can find it difficult to refinance on the interbank market (also because of the shortage of valuable collateral), and will therefore resort more to central bank liquidity than banks in countries to which money is flowing.

Germany is a good example of this mechanism: the volume of central bank refinancing attributable to German banks decreased from €250 billion at the start of 2007 to €130 billion in 2010 (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2011b), signalling that German banks have been reducing on average their reliance on central bank liquidity. Symmetrically, demand for ECB liquidity from banks located in troubled countries increased considerably over the same period. In light of these considerations, TARGET2 imbalances can therefore be interpreted as evidence of a changing distribution in countries’ refinancing operations, and as a compensation mechanism that allows sound banks in stressed countries to cover their liquidity needs.

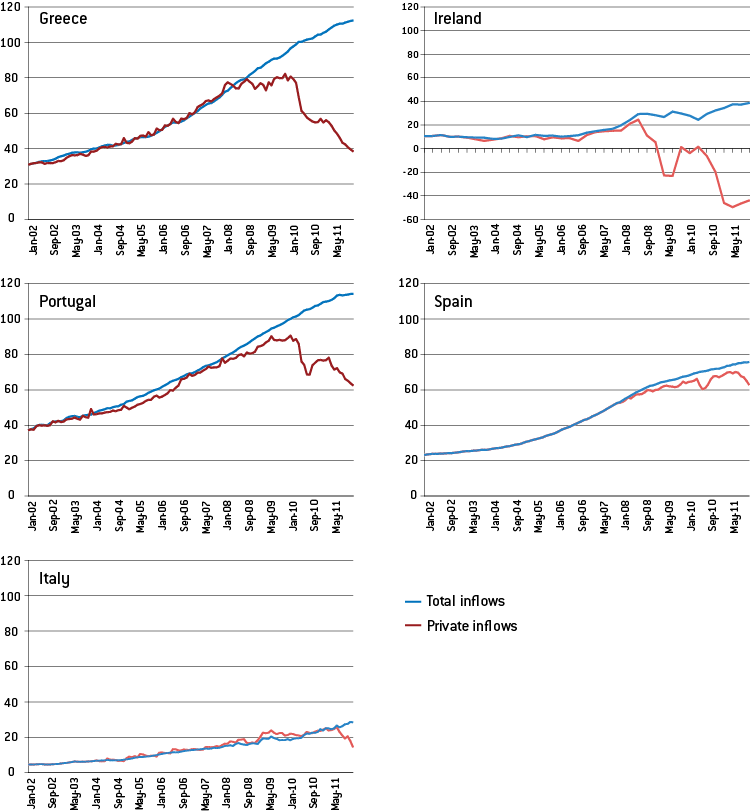

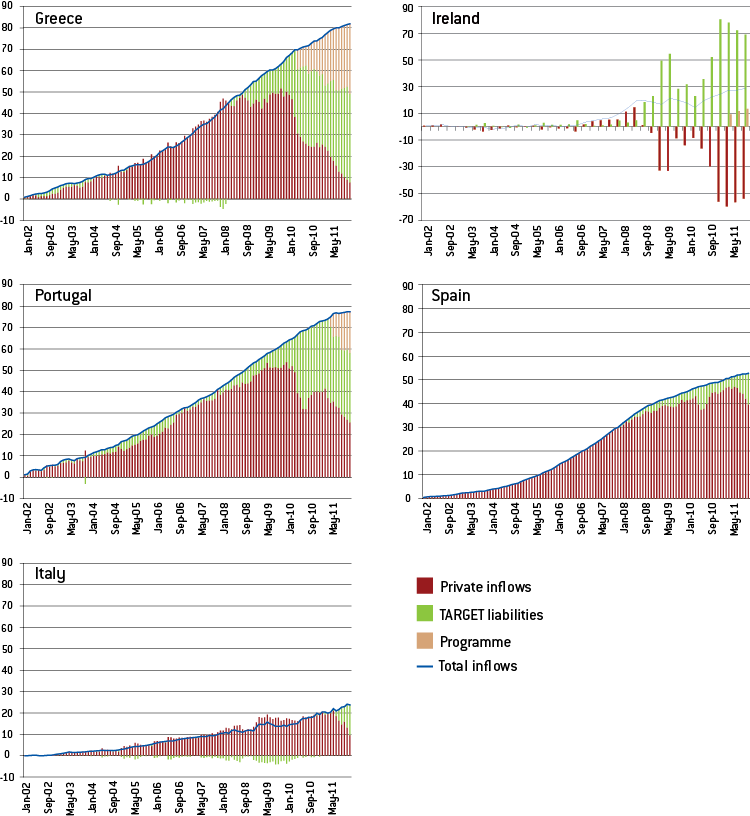

As we want to focus on inflows and reversals, not short-term fluctuations, and to compare evolutions across countries, we plot cumulated capital inflows for all countries in proportion to their 2007 GDPs, taking as a starting point the end-2001 net investment position of the country as recorded by Eurostat7. Figure 2 presents the results for Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain. In each case the blue line gives total cumulated flows, and the red line total cumulated private flows.

Figure 2 provides evidence that all five countries experienced significant private capital inflows from 2002 to 2007-09, followed by unambiguous and rather sudden outflows. In Greece inflows and outflows each amounted to about 40 percent of 2007 GDP. In Ireland inflows were limited but outflows reached 70 percent of 2007 GDP. In the other three countries outflows were less sizeable and started later, but nevertheless they were of significant size.

Figure 2: Total and private capital inflows, selected southern euro-area countries, 2002-11 (% 2007 GDP)

Source: Bruegel calculations based on national and Eurostat data. Figures show cumulative capital inflows relative to the international investment position debt in 2001.

It is interesting also to observe the timing of reversals: capital stopped flying into Greece even before the announcement in October 2009 by the Papandreou government that public finance data had misreported deficit and debt. In Portugal there was a noticeable outflow at the time of the first Greek programme in spring 2010, followed by a second outflow in early 2011. In Ireland, private capital inflows dropped the first time in the early stage of the financial crisis (2008Q3). The outflow then paused temporarily, starting again when the Greek programme was agreed in the second quarter of 2010. In Spain also there was a first, short-lived outflow in spring 2010, followed by a second, in summer 2011, concurrent with the one experience by Italy.

4 Evidence for sudden stops

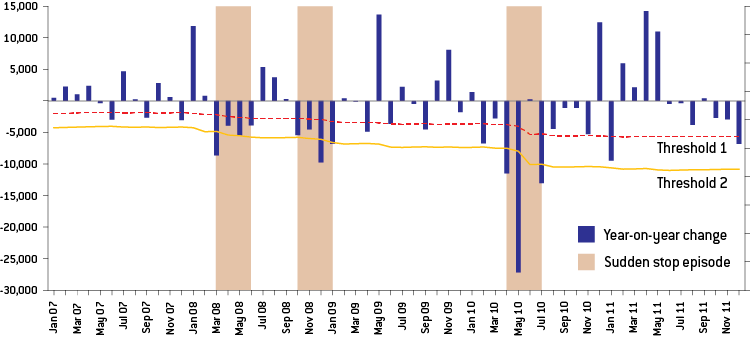

Figure 2 provides prima facie evidence of sudden stops of capital inflows. We complement this observation with a more formal test based on the standard methodology introduced by Calvo et al (2004). The Calvo methodology is based on monthly data and identifies a sudden stop as an episode in which there is at least one observation with year-on-year capital inflows two standard deviations below the mean. Calvo’s methodology has two advantages: it provides a more rigorous and systematic comparison of the experience within the euro area with the experience of emerging countries; and it dates the sudden stop.

After a sudden stop has been identified, it is considered to start with the first observation for which capital inflows are one standard deviation below the mean, and to end with the first observation for which capital inflows return above one standard deviation below the mean (see Appendix 1 for details). In Figure 3, we present the application of this methodology to the case of Greece. The grey areas correspond to sudden stop episodes.

Figure 3: Identifying sudden stops: Greece (€ millions)

Source: Bruegel.

It is apparent in Figure 3 that the Calvo methodology provides a straightforward way to identify a sudden stop that takes place after a sustained period of capital inflows, but the methodology yields more ambiguous results when it comes to identifying sudden stops that take place during protracted periods of capital outflows. An alternative to the Calvo methodology is to freeze the thresholds after the first episode, instead of de facto toughening the criterion, as apparent in Figure 3. We use both methodologies, and find no significant difference in results except for Ireland, for which the fixed-threshold methodology results in the identification of a series of sudden stop episodes throughout 2010 (see Appendix 1).

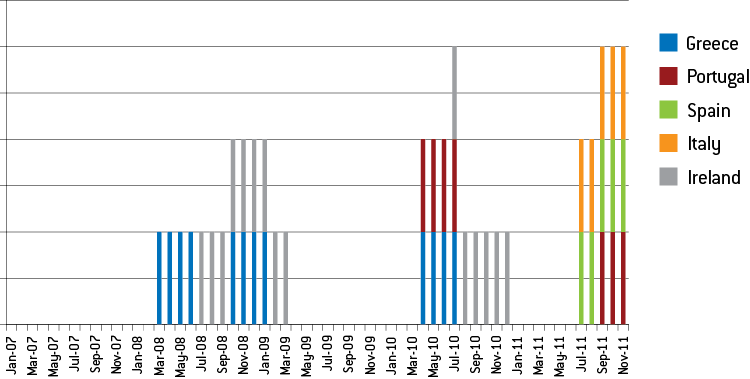

The dating of sudden stop episodes helps identify contagion effects, showing how reversals of capital flows spread among crisis countries. Figure 4 shows the number of countries in a sudden stop episode (counting only episodes of at least three months in order to eliminate short-term variations). We find three sudden stop periods:

- The global financial crisis. The rise in risk aversion and the clogging of the interbank market affected both Greece and Ireland. Capital started flowing out of Greece early in 2008 (between March and June), before the Lehman shock and well before the misreporting of fiscal statistics was revealed. This phase was followed by another episode between October 2008 and January 2009, corresponding with the intensification of the financial crisis. At the same time, private capital also started leaving Ireland, which entered a long sudden stop phase (2008Q3 to 2009Q1).

- Spring 2010. The agreement of the IMF/EU programme marked the beginning of a third Greek episode (April 2010 to July 20108), which also triggered an impressive contagion effect. Portugal entered a sudden stop immediately but it was relatively short, whereas Ireland experienced a serious and prolonged capital outflow that eventually led the country to ask for support.

- End 2011. The third wave of sudden stops involved Italy9 and Spain – both put under increased scrutiny and pressure by sovereign bond markets during the summer – and Portugal. Contrary to reasonable expectations, we cannot detect (at least using Calvo’s methodology) any episode of sudden stop for Portugal in May 2011, even though the cumulative capital flows continued to fall steadily. In this respect, it is important to recall that we are not taking the Securities Markets Programme (SMP) out of the financial account and this could partly account for the overestimation of capital inflows.

Figure 4: Sudden stop episodes in southern euro-area countries, 2009-11

Source: Bruegel.

An important question is whether capital outflows simply result from sovereign crises, ie from the disposal by non-residents of their portfolios of government securities, or if their impact is broader, also affecting solvent private agents10. It is only in the second case that it is justified to challenge conventional wisdom and speak of balance-of-payment crises instead of sovereign crises. Lack of detailed comparable data does not make it possible to proceed to a formal test, but discussion can draw on orders of magnitude in the cases of Italy and Spain.

In the Italian case, data holdings of government debt by agents measured at nominal value are available and can be compared to balance-of-payment flows. Outflows during the end-2011 episode were significantly larger than the selling of government bonds by non-residents, which suggests that other agents were also affected by the sudden stop. For Spain, the same can be done but with quarterly data only. Again, the data indicates that the outflows meaningfully exceeded what could be accounted for by the withdrawal of non-residents from the government bond market. These are rough assessments only, and our estimate of capital outflows is admittedly imperfect because we do not take into account the impact of the SMP. But our reading of the evidence is that the data tends to confirm the view that capital outflows exceeded what can be explain by the withdrawal of non-residents from the government bond market.

5 The role of official financing and the TARGET2 debate

The evidence presented in section 4 shows that the three programme countries – and more recently Italy and Spain – have experienced significant reversals of capital inflows. This was not evident from the official balance-of-payment statistics, because the private capital outflows were compensated for by an equally sizeable increase in public capital inflows. These flows have prevented the official financial account from shrinking.

Public support has taken three forms in the euro area: EU/IMF assistance programmes; provision by the Eurosystem of liquidity to the banking sector (captured by the development of TARGET balances); and ECB purchases of sovereign bonds under the SMP. As previously discussed, we have not been able to build estimates for the third component, so our estimates of private capital inflows tend to err on the optimistic side.

Figure 5 shows the relative size and importance of the two first components in filling the void left by private capital flight. The decomposition is obtained simply by cumulating separately changes in TARGET net liabilities, programme flows, and our measure of private capital inflows over the same period (2002-11) for all countries. The sum of these three components has been plotted against the cumulated total inflow (the official financial account data).

Figure 5: Decomposition of cumulative capital inflows (% of 2007 GDP)

Source: Bruegel based on national central banks, IMF, ECFIN, EFSF.

For Greece, at the end of 2011, programme and TARGET liabilities accounted respectively for 44 percent and 56 percent of total official financing. For other countries, however, TARGET financing was by far the largest component. Intra-Eurosystem liabilities amounted to 69 percent of GDP in Ireland (at end-2011Q3) and 32 percent in Portugal (December 2011), against only 14 percent and 19 percent respectively accounted for by the programme in the two countries. ECB financing has also been sizable in Italy and Spain, amounting to 13 percent and 11 percent of GDP respectively, as of November 2011.

These findings help to shed light on the debate on the role of TARGET2 financing. Early contributions focused mostly on the link between TARGET balances and current-account balances, arguing that the former financed the latter to some extent. As we have shown, the pace of current-account adjustment in the euro area was clearly much slower than for non-euro area EU countries. Substitution of private-capital inflows by public inflows, especially Eurosystem financing, helped accommodate persistent current-account deficits in a context in which capital markets were no longer willing to accommodate them.

However, large current-account balances per se are neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for incurring significant TARGET liabilities (Bindseil and Winckler, 2012). What was instead crucial was how these current-account balances were financed in the euro area before the outbreak of the financial crisis. As stressed by the European Commission already in 2006 (European Commission, 2006), the countries with large current account deficits (Greece, Portugal and Spain) were mostly financed via portfolio debt securities and bank loans, whereas the contribution of foreign direct investment was very limited. Such a financing structure, biased towards banks’ intermediation, rendered the deficit countries very exposed to the unwinding of capital inflows, especially in a financial crisis. We have shown that a reversal of private inflows indeed took place and that it was sizeable enough to qualify as a sudden stop. The Eurosystem has provided a buffer against the associated drying up of liquidity on the interbank market, and this is reflected in the evolution of intra-Eurosystem claims.

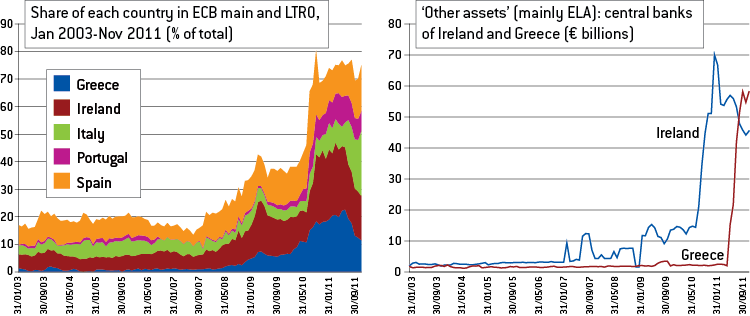

Reliance on Eurosystem financing primarily reflects the distress of euro-area banking systems in the aftermath of the global crisis. The difficulty that banks had to refinance on the interbank market led the Eurosystem to perform this standard role as a lender of last resort to the banking system through the provision of liquidity in large amounts. From October 2008 onwards, the fixed rate, full allotment procedure adopted by the ECB made a large part of the euro-area banking system reliant on central bank financing, while weak banks in distressed countries ended up taking up a disproportionately large part of the central bank refinancing (Figure 6).

These figures do not include the Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) extended by single national central banks to their banking systems. ELA – the risk being entirely borne at national level – has been extensively used in Ireland and more recently also in Greece, where the government has approved €60 billion in guarantees to facilitate the process (IMF, 2011). The operation is generally recorded in central banks’ balance sheets under ‘Other assets’ (Figure 6), an item that had jumped to €45 billion in Ireland and €58 billion in Greece as of November 201111. The rationale for ELA is to ensure that the banking system can access liquidity even when it faces shortages of good collateral to pledge at the ECB. Therefore, any tightening of collateral requirements that makes it more difficult for banks to access ECB refinancing could result in a larger share of the demand for central bank liquidity being covered by national emergency liquidity assistance.

Figure 6: Share of countries affected by sudden stops in take-up of Eurosystem liquidity and ELA

Source: Bruegel based on national central banks and ECB.

These developments raise an analytical question and a policy question. The analytical question is if the low cost of ECB refinancing and its long maturity (especially but not only since the launch of the three-year Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO) in December 2011) might have contributed to the increase in demand for Eurosystem financing, crowding out private capital flows. The correlation between private capital outflows and increased reliance on Eurosystem financing should be treated with care, because causality could run in both directions. However, for each of our three periods of capital outflows, we find it hard to reconcile the view that private capital could be crowded out with the sequence of events. The first period started before the adoption by the ECB of its fixed rate, full allotment procedure. In the second period, the coincidence of the drops in private capital flows experienced by Greece, Ireland and Portugal suggests that it was the change in market sentiment rather than the availability of ECB financing that triggered the rise in intra-Eurosystem liabilities. Similarly, capital outflows from Italy and Spain in the second half of 2011 took place before, not after, the extension of the LTRO to three years.

Turning to policy, several proposals have been advanced to shelter national central banks from the perceived risk involved in the accumulation of positive TARGET2 balances. This risk however must be qualified:

- As far as TARGET balances reflect the uneven distribution of central bank liquidity within the Eurosystem, they do not entail specific risks for the creditor central banks, over and above the risk from monetary policy operations. Losses from Eurosystem monetary policy operations could occur in case that there is counterparty failure and the value of collateral posted at the ECB is not sufficient to cover the claim entirely. Such losses would however be shared by national central banks according to the extent of their participation in the Eurosystem’s capital. In other words, the possible loss faced by each national central bank would be the same, irrespective of the size of the TARGET claims/liabilities recorded in their own balance sheets. For example, the Bundesbank, being the largest shareholder in ECB capital, would bear the greatest loss even if private capital flows from the periphery had been directed massively towards France rather than towards Germany.

- The only scenario in which TARGET would represent an actual additional risk for national central banks would be if one country (or more) decided to leave the euro area. In that case, the net claims against the rest of the system would constitute an additional risk. Any approach that would be interpreted as the introduction of a hedge against the break-up of the euro would involve the risk of sending the message that this break-up is indeed likely.

- Any proposal to limit the size of TARGET balances to a fixed threshold underestimates both the importance of a smoothly functioning payment system in a currency union, and the risk of speculative attacks that such limits would imply. The purpose of introducing the single currency was to overcome the weaknesses of fixed-exchange regimes, and this requires all capital flows between members to be treated in the same way. Placing caps on the size of TARGET balances would imply that euros would be entirely fungible across countries only up to a limit (Bindseil and Koenig, 2012), and this would in turn implicitly amount to the creation of two currencies. The threshold would offer a clear target to speculators in the same way that limited reserves offer a target in a fixed exchange-rate regime. Other proposals include the ‘collateralising’ of the TARGET balances of weaker countries and their disposal for an annual settlement (Sinn and Wollmerhaeuser, 2012). Though more reasonable in principle, such solutions would be very difficult to implement safely at present, given the size of TARGET balances and the shortage of good collateral. Again, an approach of this sort would give an incentive for speculation against the possibility of the exhaustion of collateral reserves or the inability/unwillingness of countries to mobilise resources for periodic settlements.

TARGET2 balances are the symptom of the uneven distribution of central bank liquidity within the Eurosystem. Those who focus on TARGET2 imbalances as having significance beyond this confuse consequence and causes. Rather than tinkering with the symptom, with the risk of creating doubts about the very viability of the euro, attention should focus on curing the disease, in other words the underlying banking-system problems.

The Eurosystem can tackle the short-term high demand for liquidity by weak banks, against collateral of declining quality, by tightening the quality of the required collateral. This would be likely to reduce TARGET imbalances and is an option the central bank can consider without hampering the functioning of the euro area. Naturally, however, it can only be contemplated if banks are adequately recapitalised and if the threat of a vicious circle of bank and sovereign insolvency is removed. The introduction of a three-year LTRO at the end of 2011, and the extension of the range of eligible collateral, resulted from the Eurosystem’s assessment that the risk of a funding crisis in major countries was significant enough for a massive provision of liquidity to be necessary, even though it implied almost by definition a widening of the TARGET imbalances. Only if the situation normalises further will the Eurosystem be able to mop up liquidity, reinstate its collateral policy and thereby contribute to the gradual unwinding of these imbalances.

This, in turn, requires underlying factors that contribute to bank weakness to be addressed: bad loans on bank balance sheets must be provisioned, and recapitalisation must take place wherever needed; public finances must be made convincingly sustainable; and on the macro front, persistent current account deficits can also be tackled through the Excessive Imbalances Procedure adopted as part of the so-called Six Pack legislation12. Private capital flows will only return after the disease has been addressed.

6 Conclusions

European monetary union involved from the outset many ‘known unknowns’ and a few ‘unknown unknowns’. The possibility that countries within the monetary union would experience balance-of-payment crises belonged to the latter category: conventional wisdom in research and policy was that among euro-area countries, the balance of payments would become as irrelevant as among regions within a country. Yet developments since 2009 have challenged the wisdom of this view.

We have examined in detail the financial account of five southern European countries, and have provided evidence of a dramatic reversal in their private components. Considering only the private capital flows, we find that all countries have undergone episodes of sudden stops, more usually seen in emerging markets. These episodes were clustered in three phases (the outbreak of the global financial crisis; spring 2010 at the time of the launch of the Greek programme; and the second half of 2011), which suggests that there has been contagion across countries.

Countries within the euro area can experience such crises because they do not exhibit the same degree of market and policy integration as regions within a country. Regions rarely rely on their own banking systems, implying that the bursting of a regional credit bubble will not translate into a banking crisis. Should a banking crisis nevertheless develop, it does not affect the regional state because responsibility for bank rescue and restructuring is generally a federal competence. Regions therefore can hardly be subject to confidence crises of the sort that affected euro-area countries.

A striking feature of the euro-area crisis is that whereas capital outflows have been dramatic, the current accounts of deficit countries have adjusted only partially. Decomposition of capital inflows highlights the crucial role of Eurosystem financing in mitigating the effect of private capital outflows (with a contribution of international financial assistance of a comparable order of magnitude in the case of Greece). The injection of liquidity has helped accommodate persistent current-account adjustments in the southern part of the euro area, but most importantly it has protected countries that could no longer rely on adjusting their exchange rates from the full negative impact of a sudden stop. Given the level of integration of euro-area financial markets, the effects of unmitigated sudden stops in southern Europe would have endangered the entire system and put at risk the survival of the single currency.

The smooth functioning of a payment system is essential for maintaining the stability of the financial system, preserving confidence in the common currency and allowing the implementation of a single monetary policy. Introducing constraints on the operations of the payment system would suggest an unwillingness to provide unlimited liquidity across the euro area and open a window for speculation. The more important question is how to address the underlying disease. Together with a gradual mopping up of exceptional liquidity provision and the tightening of collateral requirements, the cure is likely to require interventions to foster the sustainability of public finances, the resilience of the financial system and the reduction of the remaining external imbalance. However, confidence cannot be regained overnight; in the meantime, the Eurosystem should not be blamed for playing fully its role.

For the longer run, the evidence that the euro area went through internal balance-of-payment crises should be taken as a clear signal of weakness and as an invitation to reform its structures. Contrary to common belief, a monetary union of this sort is closer to a fixed exchange-rate system among independent countries than to a fully integrated economy. Financial-market participants have realised this and certainly will not forget it. In response, the fostering of a pan-European banking industry and the creation of a banking union with centralised supervision and access to resources to recapitalise weak financial institutions should feature high on the policy agenda. Only a closer integration of markets and policies will preserve the euro area from the risk of further attacks.

Source : Bruegel