In the decades immediately after World War II, many private employment agencies in the US were owned by women. This column investigates whether these women-owned agencies helped female jobseekers obtain better jobs. The authors find that women-owned agencies provided more opportunities to women by expanding the agency services available to them, including help finding male-dominated and skilled jobs. But while women-owned agencies advertised higher wages for women than male-owned agencies, this appears to have been because they specialised in clerical jobs, not because they mitigated discrimination.

Employer discrimination against women, whether due to prejudice or ignorance, reduces the quality of job matches and women’s pay. The process by which women and men are matched to jobs is important not only for equity reasons but also because good matches are important components of productivity. Intermediaries such as private employment agencies may improve the quality and speed of matches, including by reducing discrimination and providing more accurate assessments of jobseekers’ skills.

Although a large literature has considered discrimination against women (e.g. Card et al. forthcoming, Kuhn and Shen 2012, 2021, Severson 1939), there is little research on private employment agencies (Stanton and Thomas 2016) and none on discrimination in connection with private employment agencies. In the decades immediately following WWII, many private employment agencies in the US were owned by women. In recent work (Hunt and Moehling 2024), we investigate whether these women helped female jobseekers obtain better jobs.

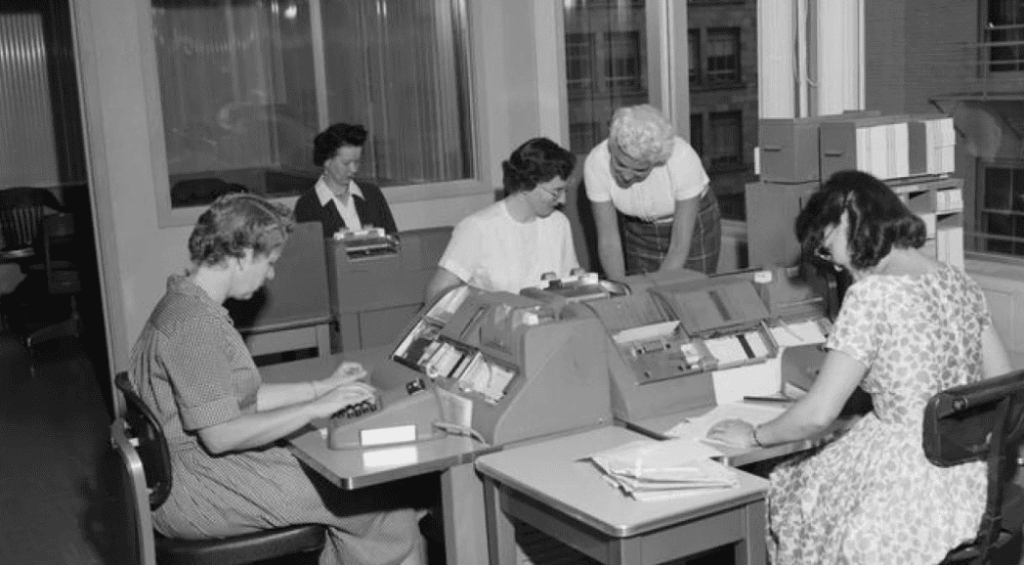

Private employment agencies sought to match jobseekers, who were not necessarily out of work, to employers, generally to fill vacancies for non-temporary positions. Agencies established relationships with client firms by cold calling or by using prior contacts, such as hiring agents who formerly worked in personnel (human resources) departments. Once relationships were established, firms would contact the agency with requests for referrals (Martinez 1976, New York Court of Appeals Records 1939).

Client firms sought guidance from employment agencies on what wage to pay (New York Times 1951), which might have influenced other firm decisions, such as the gender of the hire. In selecting which jobseekers to refer, agencies would interview jobseekers and might administer skills tests and check references. Agencies also supported jobseekers by giving guidance on interview techniques and writing resumes. The jobseeker would pay a fee if placed in a job.

The establishment of the female-owned agencies may have mirrored the practice of minorities escaping discrimination by setting up their own firms, either to employ members of their minority group (including themselves) or to serve customers from their minority group (Wald 2008, Halperin 2012). Female-owned agencies may have specialised in placing women and exerted more effort in placing women than other agencies. Further, female-owned agencies could conceivably have mitigated employer discrimination against female jobseekers by persuading employers that they were operating inefficiently by underestimating women and should offer better jobs or possibly wages to women.

However, female proprietors could themselves have faced discrimination from client firms, which may have been reluctant to entrust them with their male vacancies. Conversely, female jobseekers may have favoured female-owned agencies, believing they would be treated with more respect and perhaps taken more seriously.

To study how job advertisements posted by female sole proprietors differed from those posted by male sole proprietors, we use historical ‘help wanted’ advertisements and archival data on agency owners. Prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it was both legal and standard for a job advertisement to specify the desired gender of the job applicant. We recorded gender and other information from 14,000 advertisements posted by 366 employment agencies in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Baltimore Sun in 1950 and 1960. From business registers in county clerks’ offices, we identified the owners of those agencies that were sole proprietorships. Women owned 31% of the agencies we consider and posted 21% of the agency ‘help wanted’ advertisements. Thirty-eight per cent of job advertisements were posted by male-owned agencies, which represented 37% of agencies. The remaining agencies were predominantly corporations.

As predicted, female-owned agencies specialised in female jobseekers: 61% of their advertisements were for women compared to 32% for male-owned agencies. This specialisation implied specialisation in clerical occupations, and this extended to male advertisements, whose share of clerical occupations was 50% higher than for male-owned agencies.

Female-owned agencies accounted for 31% of the female job advertisements in our sample. This implies that, had those agencies not existed and all else being equal, the 31% of women jobseekers who found their job through a female-owned agency would have had to search without the help of agency services. If those agencies had instead been owned by men and remained the same size, 14% of female jobseekers would have lost access to agency services.

Female-owned agencies also advertised slightly better-quality jobs to women than did male-owned agencies, paying a wage premium of 5.5%, but advertised lower-quality jobs to men, advertising wages 21% lower than for male advertisements posted by male-owned agencies. The slightly higher wages for women and the much lower wages for men advertised by female-owned agencies may seem like prima facie evidence of female proprietors’ influencing advertisement content to favour women and disfavour men. However, this appears not to be the case, since among the advertisements of a given agency, female proprietors did not advertise higher wages for women and lower wages for men. Rather, female-owned agencies’ concentration on clerical jobs led to advertisements with similar wages for men and women, implying female wages similar to those at other agencies but lower male wages.

In sum, female-owned employment agencies provided more opportunities to women by expanding the agency services available to them, including help finding male-dominated and skilled jobs. The specialisation in vacancies for women may have simply been a choice by female proprietors as to which requests from client firms to accept, but it is likely that female jobseekers were attracted to female-owned agencies, leading client firms seeking women to be attracted to female agencies.

This equilibrium could have been reinforced by female proprietors developing a comparative advantage in assessing workers for clerical jobs, including for men, or in assessing women. Alternatively, the specialisation could have been imposed by client firms who did not trust them to fill high-skill – and therefore more male – vacancies.

Although female-owned agencies advertised higher wages for women and lower wages for men than did male-owned agencies, this appears to have been mostly the result of specialising in clerical jobs rather than of discrimination mitigation.

Source : VOXeu