In higher-income countries, urban proximity has been shown to enhance workers’ skills and income, but less is known about low- and middle-income countries. This column examines how the income of initially poor workers in Brazil changes after urban migration. Wages go up immediately for migrants to both southern and northern Brazilian cities, but only in the wealthier southern cities do initially poor migrants see a longer-term positive effect. Workplace segregation appears to play a key role, as southern firms do more to bring skilled and unskilled workers together.

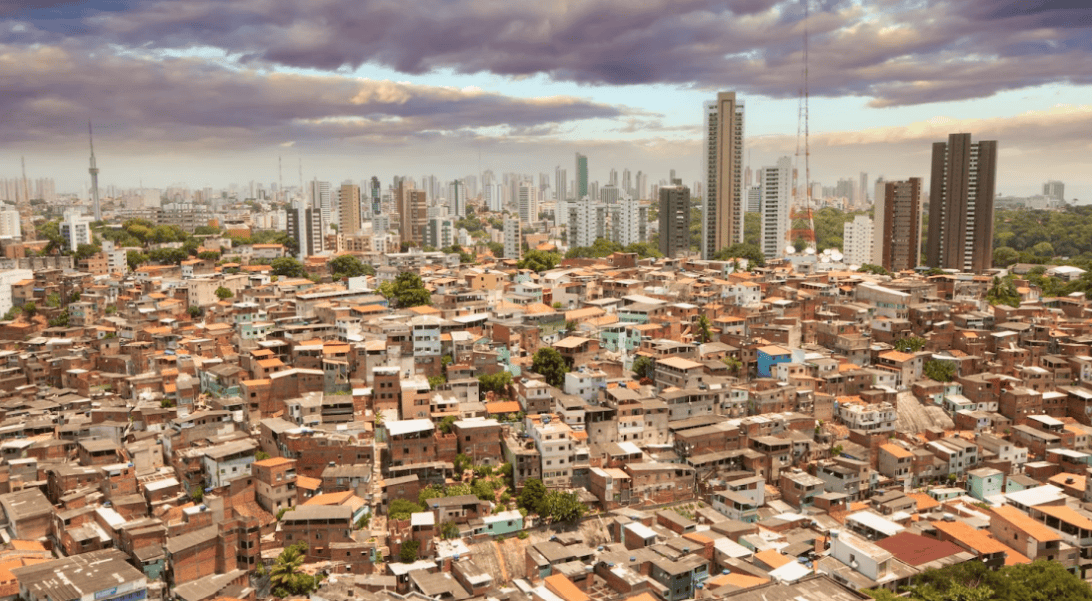

Are the slums of South Asia or the favelas of Brazil poverty traps or portals to prosperity? Marx et al. (2013) document that the longer-term residents of Nairobi’s Kibera are no richer than new arrivals and that the longer-term residents of Bangladeshi slums are much poorer than the newcomers. But do these cross-sectional relationships indicate permanent desperation, or do they just show the outcome of a sample stuck in a slum after decades in a big city?

Janice Perlman’s (2010) superb book Favela tells a different story. It follows the children and grandchildren of the residents of a Brazilian slum in 1969, revealing enormous economic progress. While 72% of the grandparents’ generation were illiterate in 1969, that share had fallen to 45% overall by 2001 and only 6% of the grandchildren were illiterate. While only 6% of the grandparents did non-manual work in 1969, 37% of their children and 61% of their grandchildren did non-manual work.

Yet neither of these significant pieces of research provides a clear answer about the treatment effect of moving to and living in a slum, since Marx et al. don’t follow urbanites over time and Perlman doesn’t have a comparison group. Therefore, even before addressing selective migration into cities in developing countries, we must begin with a panel of workers that tracks movement and economic success.

Glaeser and Mare (2001) used that approach and found that American cities seem to increase the growth rate of earnings, which is compatible with the view that urban proximity can enhance human capital accumulation. The gold standard for such work is now De la Roca and Puga (2017), who used Spanish administrative data to estimate the treatment effect of working in different Spanish cities. However, while significant geographic inequalities in standards of living persist in countries at different stages of development (e.g. Dingel et al. 2020, Moretti and Diamond 2022), the De la Roca and Puga method could not be used in much of the non-high-income world, because in low- and middle-income countries, less-skilled workers are overwhelmingly in the unmeasured, informal sector.

In a recent paper (Barza et al. 2024), we focus on Brazil, a middle-income country with large spatial inequalities and disparities across and within cities (Musacchio et al. 2014, World Bank 2023). Brazil is now sufficiently formal that an administrative dataset provides significant information about the economic lives of the poor. We use anonymised administrative data (RAIS) collected by the Brazilian Ministry of Labor and Employment to track the earnings trajectories of 675,000 initially low-wage workers across all of Brazil.

We follow De la Roca and Puga closely, especially their distinction between initial and medium-term (7.7 years) urban wage premia, to compare the impact of agglomeration in Spain and Brazil. In their benchmark estimate, the elasticity of initial wages to the logarithm of agglomeration size is .022, which is close to our initial wage elasticity of .024. Their medium-run elasticity, however, is .050, which is considerably larger than the .030 estimate that we find in Brazil. When we focus on initially poor men, we estimate a short-run elasticity of .020 and a medium-term electivity of .039.

The initial impact of coming to a city seems to be roughly comparable in Spain and Brazil, but there does seem to be more learning in the Iberian cities. Brazil’s cities, taken as a whole, promote upward mobility for the poor but not quite to the degree seen in the wealthy Global North. Does the gap between Brazil and Spain mean that the level of economic development, both across and within countries, determines the ability of cities to promote upward mobility for the poor?

Like the US 75 years ago, Brazil has a vast economic divide between north and south. Northern Brazil, like America’s old South, is more tropical, less industrial, and still shaped by the legacy of an economy once based on chattel slavery. Northern Brazilian cities are poorer and more closely tied to local agriculture, compared to southern Brazilian cities which are considerably more industrialised. We therefore tested whether the initial and medium-term effects of urbanisation were different in the north and the south.

For initially poor men, we estimate an initial coefficient on city size of .018 in the South and .02 in the North, which are similar to each other and to the De la Roca and Puga estimates for Spain. The southern workers were paid more, but their initial wage premia were no more strongly correlated with city size than the premia in the north (Figure 1). The figure shows that the premia are higher in the south, but the correlation with city size is similar.

Figure 1 City size and premia for the initially poor

Source: Barza et al. (2024).

But in the medium term, the coefficient in the south is .042 and the coefficient in the north was still .020. The southern cities display wage growth for the poor that is almost at European levels. The northern cities have no medium-run wage growth effects. These results suggest that while Perlman (2010) was right about Rio, maybe the cities of northern Brazil are poverty traps.

What’s behind the north-south divide?

The modern literature on urban agglomeration was kickstarted by Robert Lucas’s seminal 1988 article in which he writes

… it seems to me that the ‘force’ we need to postulate account for the central role of cities in economic life is of exactly the same character as the ‘external human capital’ I have postulated as a force to account for certain features of economic development.

Lucas’s work directly inspired Rauch’s (1993) also-seminal article on human capital externalities, which used city-level data to estimate magnitudes similar in size to the magnitudes based on aggregate figures reported in Lucas (1988).

Lucas’s theory of human capital externalities implies that cities will promote learning when they connect younger workers with people who are more experienced. Rauch took this to mean that people should be expected to earn more in more-skilled cities and to pay for that privilege with higher housing costs. He found both facts to be true in the US, and later work confirmed these patterns in other parts of the world (Moretti 2004). Yet our estimates of both the initial and medium-term wage premia are negatively correlated with the share of workers in the area who have a college degree. The puzzling fact seems related to the large role that the public sector plays in employing the educated, especially in northern cities.

Lucas also wrote that “group interactions … are central to individual productivity” and these “involve groups larger than the immediate family and smaller than the human race as a whole”, which leads us to measure the potential workplace interactions between skilled and unskilled workers. For over 60 years, social scientists have focused on residential segregation, yet our economic lives are shaped far more by our place of work than our place of residence. Consequently, our paper follows the literature that focuses on experienced segregation (Athey et al. 2021).

As the administrative data enables us to see who works with whom, we can measure the economic segregation of the poor at the establishment level. For each metropolitan area, we calculate the average share of the workforce that is not poor in the average poor person’s workplace. We then subtract the overall share of the city that is not poor to capture the mixing between poor and not poor that occurs at work beyond that implied by the city’s poverty rate.

Workplace segregation powerfully predicts both the initial and medium-term wage premia. Moreover, the gap between south and north largely disappears when we control for exposure of the poor to non-poor workers (Figure 2). Northern cities have smaller firms that seem to do simpler things and segregate the less skilled. Southern cities appear to do more complex things that bring skilled and unskilled workers together. One of the many benefits of economic complexity (Hidalgo and Hausmann 2009) is that it creates settings where people with different skills work together and potentially learn from one another.

Figure 2 Exposure and premia for the initially poor

Source: Barza et al. (2024).

We view these results as supporting the long-standing hypothesis that we learn much from our coworkers but that these learning opportunities are shaped in part by economic structure. The great challenge to interpreting our results is that segregation is not exogenous and workers are not randomly allocated across cities. We hope that future work will leverage both shocks to workers – that push them from more segregated firms to more integrated firms – and shocks to establishments or places to identify the causal impact of workplace segregation on workers’ long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

We began this essay by asking whether the cities of poorer nations provided upward mobility for poor young workers. While our data only allows us to answer this question for Brazil, it shows that southern Brazilian cities appear to be places of opportunity: wages go up immediately for migrants to these cities and there is an even larger impact in the longer run. Northern Brazilian cities offer an immediate wage bonus but show less sign of a permanent positive trajectory. The data supports the view that these differences can be explained by segregation at the workplace level.

What does this mean for cities in lower-income countries? Existing evidence does not indicate that policymakers should try to stop rural-urban migration, but there are reasons to fear that upward mobility may be limited by workplace segregation. We hope that future research will advance our understanding of the correlates of upward mobility of cities in low- and middle-income countries and help identify policies to ensure that cities will turn low-income children into middle-class adults. We suspect that at least some of these policies will work by generating greater interactions between more- and less-skilled workers.

Source : VOXeu