The economic costs of armed conflict – in terms of lost income and reduced physical capital – are borne overwhelmingly by the countries in whose territory the fighting takes place. Yet, wars also impose costs on other countries, particularly those geographically closest to the war site. This column suggests that adverse supply‐side spillovers, a pervasive feature of war, tend to last longer than other supply shocks. In recent years, central banks have responded to these shocks – including the war in Ukraine – by tightening monetary policy, a strategy the authors broadly support.

The global political and economic landscape is undergoing profound changes. Geopolitical tensions are rising and rivalries between nations are breaking into the open (Ayiar et al. 2023). The process is fuelled by a volatile blend of rising nationalism (Colantone and Stanig 2017) and shifts in power dynamics (e.g. Baldwin 2024) — the two most common reasons that nations go to war, as we show in a new comprehensive study of wars and their economic fallout since 1870 (Federle et al. 2024a). 1

Wars cause death and destruction, disrupt trade, and wreak havoc on public finances. For countries that experience war on their own soil, this typically amounts to an outright economic disaster. However, wars and the associated rise in military spending can also have expansionary effects and help pull economies out of depressions. The productive potential of an economy is a powerful factor deciding the outcome of wars. War is therefore important for economics, and better understanding the economics of war is a priority for economists.

To date, there is only limited evidence on the macroeconomic impact of interstate wars and basically none on their macroeconomic international spillovers (for the former, see Chupilkin and Kóczán 2022). Against this background, we estimate the direct economic fallout of wars for large war sites, defined by casualties in excess of 10,000 people on their own soil, as well as the spillover effects for other economies using a new data set that covers all major wars since 1870. We find that the economic toll of war is not confined to war sites or the other direct parties to the war, and we offer a structural interpretation of the evidence through the lens of an international business cycle model.

The economic impact on the war site

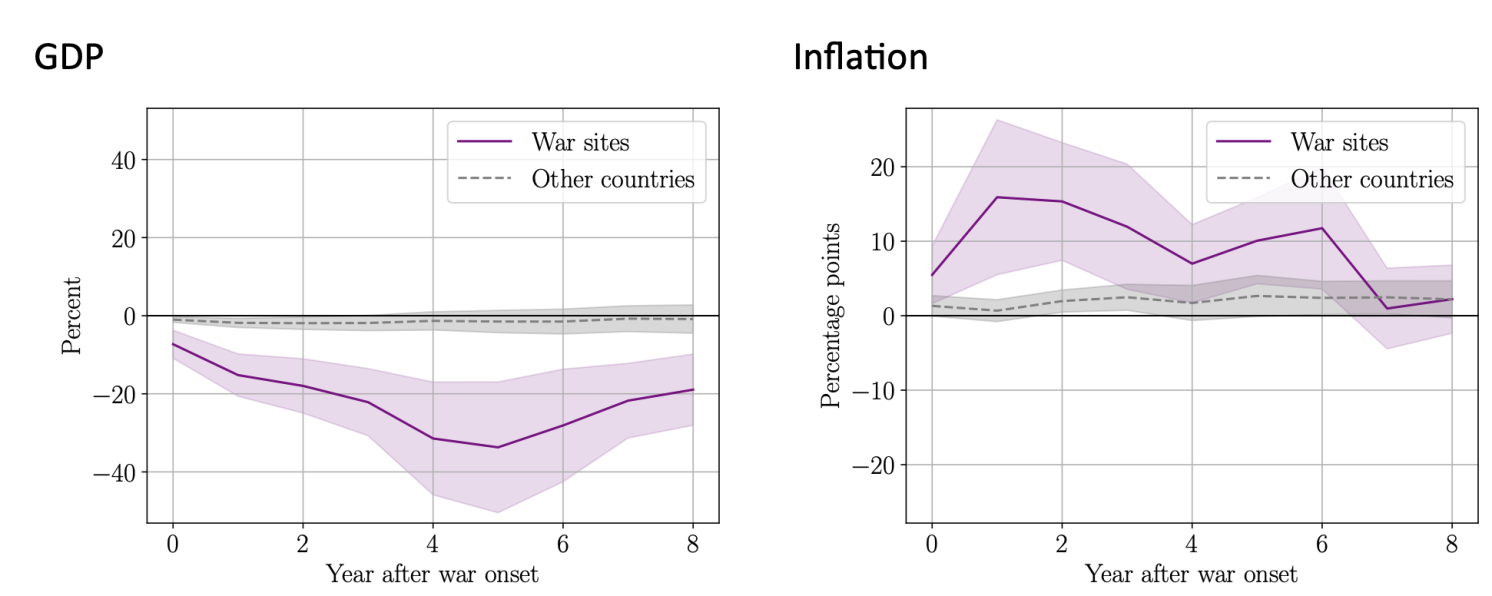

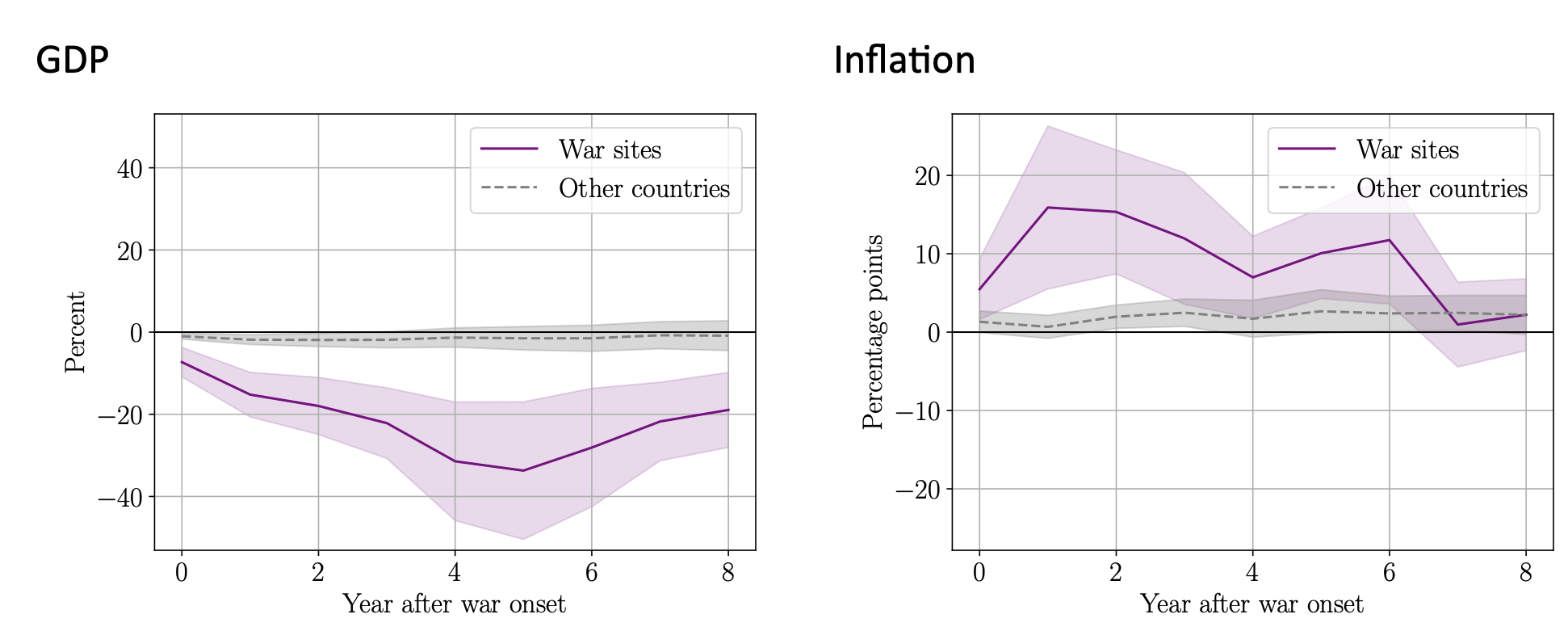

Figure 1 shows how real GDP and inflation adjust to the outbreak of war, indicated by year zero on the horizontal axis. The solid purple line shows the estimate for the war site, while the shaded area indicates statistical uncertainty (90% confidence bounds). GDP, shown in the left panel, is reduced on average by more than 30% relative to trend some five years after the war’s start. The right panel shows the response of inflation. The war site experiences a large and persistent increase in inflation. The effect peaks at about 15 percentage points in the first year following the start of the war, but remains high afterwards. In a nutshell, war represents a large and persistent adverse supply shock, with economic activity contracting amid strong inflationary pressure.

Figure 1 The economic repercussions in war sites and other countries

Notes: Figure shows how GDP and Inflation adjust in response to the start of war, in the war site (solid purple line), and in other countries (grey dashed line). Left panel shows percentage deviation of GDP from trend; right panel shows deviation of inflation from pre-war rate in percentage points. Horizontal axis measures time in years since the start of war. Shaded areas denote 90% confidence bounds.

To put these results into perspective, we stress that our estimates reflect the average effect of large wars. In our sample, the average large war site incurs almost 350,000 casualties and experiences hostilities which last for about three and a half years. As such, the average war site – in terms of casualties – is smaller than the current war in Ukraine: estimates from August 2023 already put the number of troop deaths and injuries near 500,000 (Cooper et al. 2023). Since an end to the violence is not yet in sight, we can reasonably expect this number to grow. In total, our sample comprises 38 war sites and 1,798 instances in which a country was potentially exposed to a large war taking place on foreign soil.

Spillovers to other countries

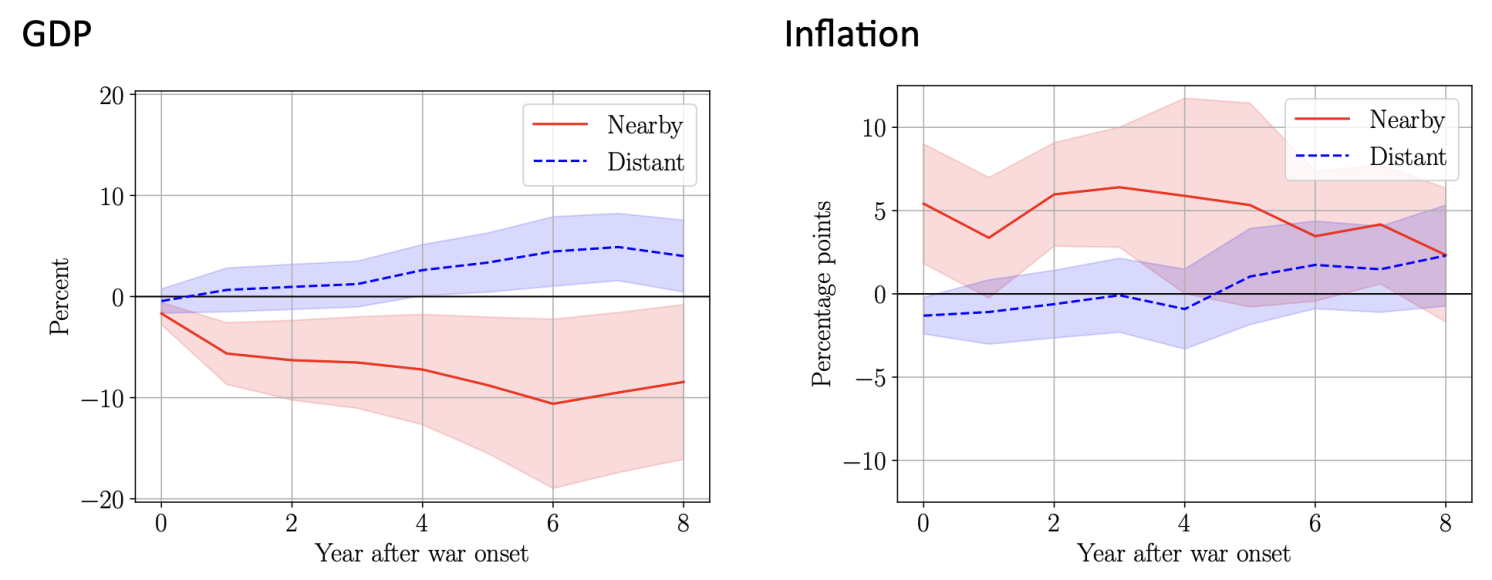

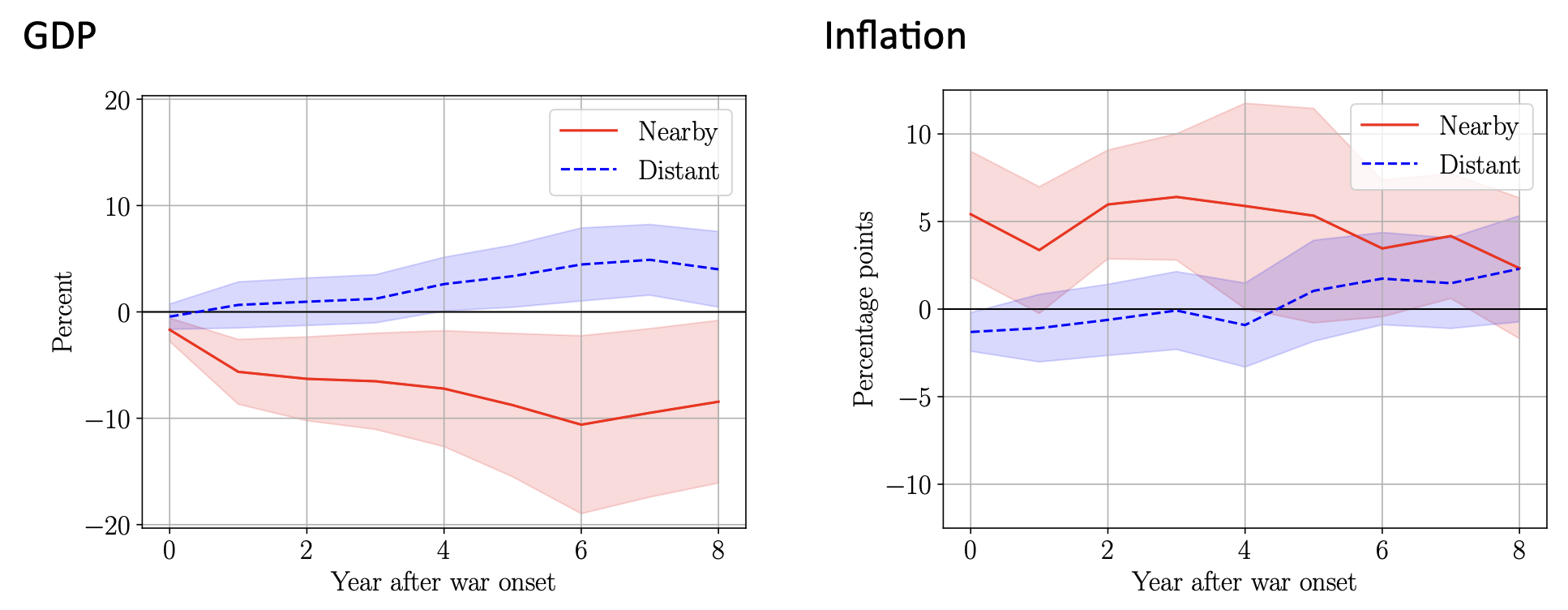

Figure 1 also shows the average spillovers in terms of GDP and inflation to other countries, depicted by the grey dashed lines in both panels. These are the countries in our sample that are not war sites, though they may or may not be a party to the war. The average spillovers on other countries are very mild. However, it turns out that these estimates mask considerable heterogeneity across countries. Figure 2 shows the responses for a specification which allows the effects on other countries to differ depending on their geographic distance from the war site. The red solid line represents estimates for a ‘nearby’ country – that is, a direct neighbour to the war site. The blue dashed line represents a country that is ‘distant’ – as far away as possible from the war site.

Figure 2 The economic repercussions in nearby and distant countries

Notes: Figure shows how GDP and Inflation adjust in response to the start of war, in nearby (solid red line) and distant (blue dashed line) countries. Left panel shows percentage deviation of GDP from trend; right panel shows deviation of inflation from pre-war rate in percentage points. Horizontal axis measures time in years since the start of war. Shaded areas denote 90% confidence bounds.

The difference across these groups is stark, and it bears noting that spillovers for actual countries will fall somewhere in the range spanned by these two limiting cases. In the nearby country, real GDP declines on impact and remains persistently weaker. Five years after the start of war, GDP has declined by almost 10% compared to the pre‐war trend. At the same time, inflation rises considerably. This suggests that the supply shock in the war site also generates strong supply‐side spillovers to the neighbouring economy. In contrast, countries located at the other end of the world experience stable inflation and even positive output spillovers.

Importantly, the effects on other countries hold independently of whether a country is a party to the war – spillovers are somewhat stronger for belligerents than for third countries, but the overall pattern is strikingly similar. Accordingly, we can exclude the possibility that the economic fallout of war on other countries is driven by actual participation in the war.

Spillovers operate via trade linkages and military spending

As we show in our paper, it is possible to explain the macroeconomic impact of war within a state‐of‐ the‐art model of the world economy. For this purpose, we assume that the war affects the war site in two ways, consistent with evidence provided in the paper. First, a sizable fraction of its capital stock is destroyed. Second, productivity declines persistently. The decline in productivity is consistent with the notion that a shift to a war economy entails significant efficiency losses. Both the destruction of the capital stock and the decline in productivity formalise the idea that war, in economic terms, represents an adverse supply shock: economic activity contracts and inflation increases, just as we observe in the data. These effects spill over especially to countries which maintain strong trade linkages with the war‐site economy.

In our model simulations, we also explicitly account for the sizable increase of military expenditures that we document during war times. In the war site, military expenditures increase by up to ten percentage points of GDP during an average war. But there is a significant increase in other countries, too, whether nearby or distant. This partly explains why GDP increases in distant countries in some instances: the boost to economic activity due to higher spending dominates adverse spillovers from the war site, which are weak in distant countries.

Central banks cannot ‘look through’ a war shock

Our findings establish adverse supply‐side spillovers as a pervasive feature of wars, and one that tends to last for a more extended period than other supply shocks. Among other things, this also points to the resulting challenge for monetary policymakers. A lasting adverse supply shock may generate an inflationary impact that the central bank cannot simply ‘look through’. Hence, our analysis broadly supports the reaction of central banks in recent years, which have tightened monetary policy in response to a series of adverse supply shocks, including – notably for Europe – the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Source : VOXeu