Land prices, as reflected in house prices relative to incomes, are near all-time records, pricing younger citizens out of home-ownership and affordable rents. This column argues that a green land value tax – a charge on the land plus a charge on the house minus a discount related to efficiency of the building’s energy usage – would help resolve conflicts around meeting climate goals, equity and housing affordability, reduce intergenerational injustice and benefit sustainable growth. The evolution from existing property tax systems would be aided by a simple new tax deferral mechanism, removing much of the sting of property tax reform.

It should be high on the agenda of every government to reform annual property taxes to incorporate discounts for energy-efficient buildings, and apply subsidies and stronger building regulations that will lower CO2 emissions. Astonishingly, the cooling and heating of buildings contributes about one-third of CO2 emissions. COP27 in 2022 warned that greenhouse gas emissions are fast approaching tipping points that will make “climate chaos” irreversible.

Land value taxes have long been considered the most efficient form of taxation. Discussion around their use has intensified as land values have risen strongly relative to incomes (Bonnet et al. 2021). A tax reform shifting taxes away from productive labour and capital (where they reduce incentives to work and save), and onto land (where they do not), would produce major long-run increases in output (Kumhof et al. 2022). Proposals for land value taxes have begun to enter the policy discussion, notably in Detroit, Michigan, and receiving significant news coverage (see the New York Times and the Economist). The optimal tax literature argues (Mirrlees et al. 2011) for a split-rate, with a higher tax rate on land than on buildings – the latter a kind of consumption tax.

Carbon emissions from the use of fossil fuels result in the most extreme negative externalities that mankind faces. Correcting this massive market failure through the property tax system is highly desirable. The climate-related potential for split-rate property taxation has not previously been addressed (e.g. by Bonnet et al. 2021 and Kumhof et al. 2022). In Muellbauer (2023), I propose that tax rates on buildings should embody discounts related to the carbon-efficiency of buildings. With fossil fuel sources of energy used in buildings still so dominant, energy efficiency offers a close substitute. In practice, the use of Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) is widespread, and EPCs currently offer the only easily available tag for offering green discounts on recurrent property taxes.

Inequality and the green agenda

Lower-income households often live in poorly insulated homes, and hence benefit less from green tax rebates or discounts. They spend a large fraction of their budgets on energy and housing, and hence can be hurt more in the short run by carbon taxes and tougher building regulations. These negative distributional effects could be offset by applying a more progressive property tax that includes green discounts. A tax that is proportional to property values, and especially one with higher rates on the land component, is progressive.

A new proposal to defer property tax based on home equity

A key objection to annual property taxes (often voiced by the wealthiest property owners) is that cash-poor households in expensive properties could face hardship. This can be addressed by permitting deferral of payment until the property is sold or transferred (OECD 2022: 87). Some jurisdictions, such as Canada, Denmark and Ireland, offer tax deferral by accumulating debt (OECD 2021a). In the US, 24 states operate deferral options for retirees. However, take-up is remarkably low, and this is true in other countries too. Munnell et al. (2022) suggest as possible reasons onerous and complex eligibility restrictions, and concern about high interest rate risk and downside house price risk.

These risks are eliminated 1 in a simple equity-based deferral scheme, first proposed in Muellbauer (2018). Every household, or at least those headed by a person of retirement age, would have the right to defer the property tax. The tax authority would register a proportionate interest at the land registry equal to the unpaid tax for each year deferred, to be settled when the property was sold or transferred. 2 For example, with a 1% tax, after ten years of deferral, the property owner would retain 90% of the then-current value of the registered property title. Moreover, an incentive in the form of a small discount for cash payments of property tax could be offered, which would help stabilise annual revenue flows for the tax authority, and roughly offset what otherwise could be seen as a subsidy to the deferrers. 3

This ‘proportion of equity’ deferral proposal is easy for taxpayers to understand. Ticking a box on the property tax form requesting deferral without having to be means-tested or to undergo complex form-filling is an advantage. Moreover, this avoids complex interest rate calculations. Research on the financial sophistication of consumers suggests many do not understand compound interest. In contrast, the fraction of value of a home owned is a simple concept. The above applies to a property tax whether in the form of a split tax or not.

No trade-off between efficiency and equity with well-designed property taxes

Economists often argue that there is trade-off between growth and an equitable distribution of income and wealth, so that policies favouring equity will damage economic growth and efficient resource allocation. However, well-designed annual property taxes do exactly the opposite: they enhance growth, efficiency, and equity.

Land ownership is far more unequally distributed than income in most countries, making a split-rate property tax, with higher rates on land, necessarily progressive, as well as efficient. Lowering of mobility-restricting transaction taxes like stamp duty while increasing recurrent property taxes would improve the utilisation of the housing stock, increase the flexibility of labour and housing markets (OECD 2021b), and ease adaption to shifts in the economic environment.

Evidence has mounted that credit-fuelled real estate booms crowd out more productive investment, with negative consequences for growth and increased risks of financial crisis. 4 These booms are mainly in land rather than building values. Property taxes, especially split-rate taxes linked to annual valuations, would dampen such booms. With appropriate green discounts, green property taxes can enhance sustainable growth. Green property tax discounts also sharpen incentives for green mortgage pricing, in the form of lower interest rates, or more favourable lending criteria for homes with better EPC ratings.

Some authors question whether with a split-rate tax, an increase in tax rates on land relative to buildings would reduce income inequality. 5 However, these studies focus only on cash income, rather than on disposable income which includes the imputed rent of owner-occupiers (owners do not pay rent). It then becomes realistic to examine the distributional implications of property taxes in terms of household disposable income. With an easy deferral mechanism, the link is broken between cash income and annual property tax. No longer is a cash-poor home-owner in an expensive location considered ‘poor’ in terms of household disposable income, but instead is well-off compared to a tenant with the same cash income but paying rent. The outcome is transformative: income inequality is reduced by raising tax rates on land relative to buildings.

Benefits of well-designed property taxes for economic and financial stability

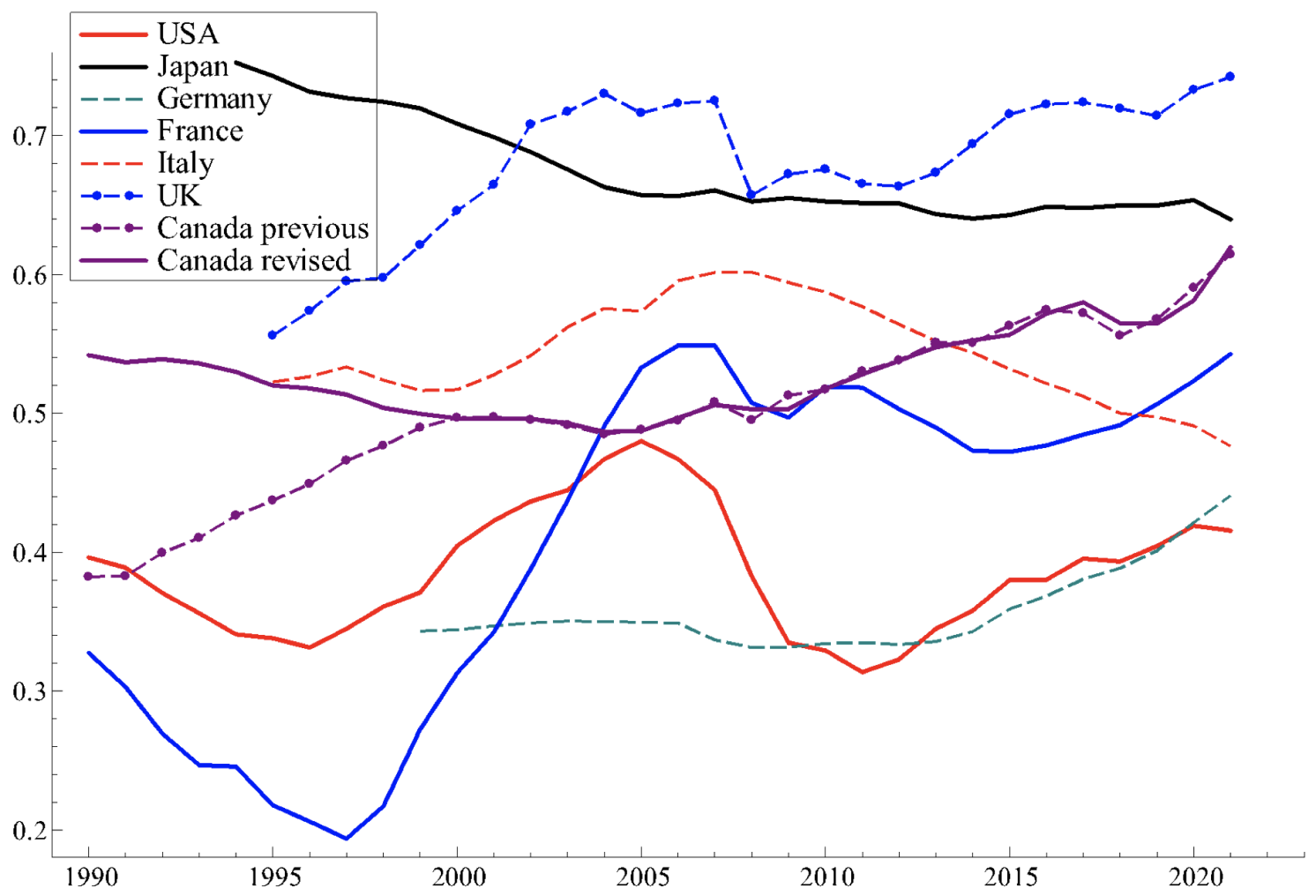

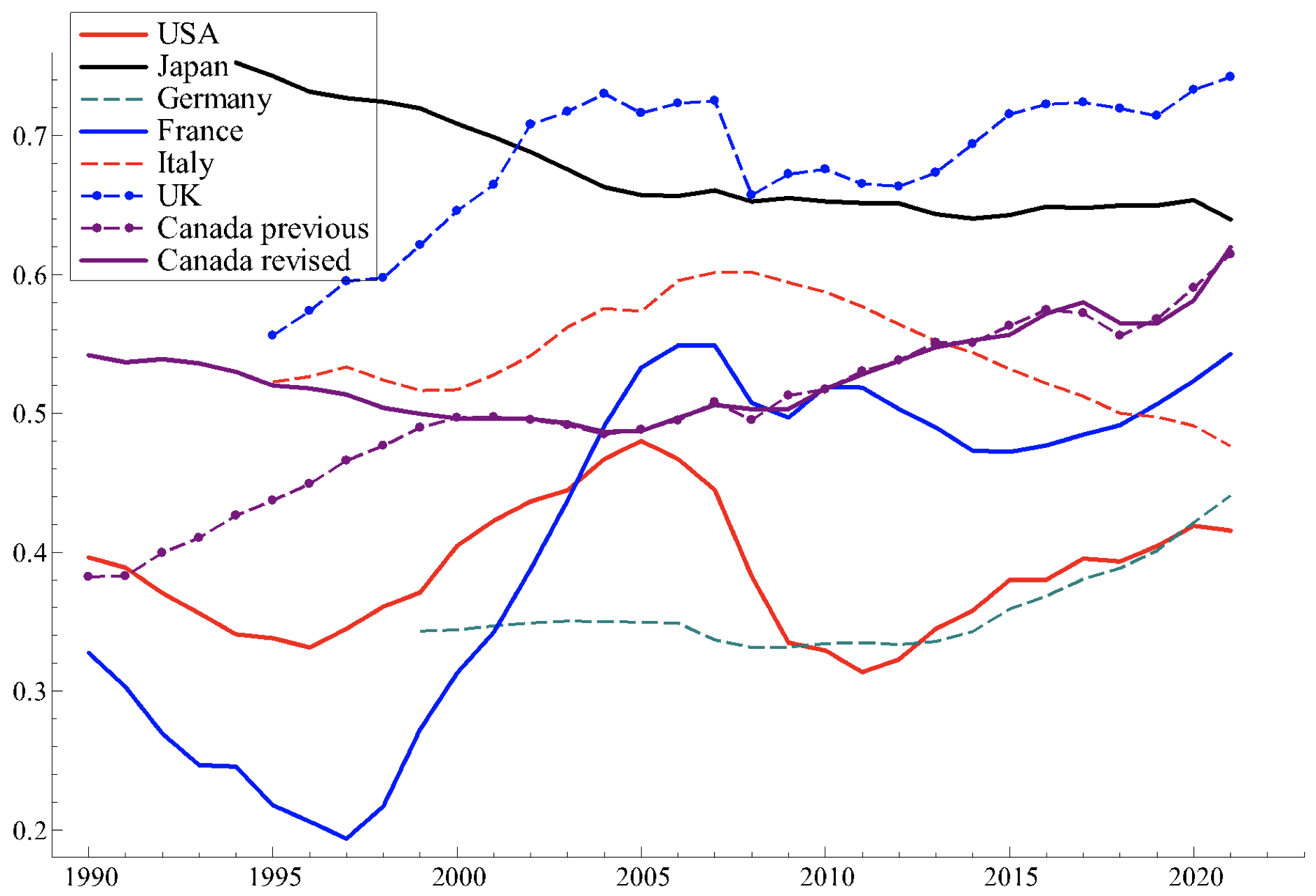

In four G7 countries – the UK, France, Canada and Japan – more than half the value of housing wealth is accounted for by land (over 70% in the UK), and no less than 40% in any of the G7. Thus, in the UK, on average, less than 30% of the value of a home is in the building itself. The share of land has risen strongly in all G7 countries, except for Italy and Japan. House values are a combination of volatile and cyclical land values and far more stable building values, given by construction costs. High and volatile land prices pose significant risks to the stability of the financial system and wider economy. Land value or split-rate taxation is especially useful to promote economic stability, and better targeted than standard property taxation.

Figure 1 Shares of land in housing wealth

Source: OECD, National balance sheets for non-financial assets owned by households and non-profit institutions serving households, share of land in fixed non-financial assets, revised data for Canada from Statistics Canada. Household fixed non-financial assets is a close approximation to housing wealth.

In the process of compiling these data, I could not make sense of the rise in the share of land in Canada from 1990 to 2000, as house prices relative to construction costs were flat, so that the same should have been true of land prices. Statistics Canada have acknowledged a serious error. 6 An error of this kind could have important policy implications. The Bank of Canada’s LENS model of the economy uses net worth, including housing wealth to model consumption. Over the period 1990-2000, net worth rose rather less than implied by their incorrect data. This would have distorted forecasts and simulations from the Bank’s policy model.

How to value land

Critics of split-rate property taxes argue it is hard to separately value land and buildings – though the recent property revaluation in Germany does exactly that. In general, there are many more transactions of ‘house plus land’ bundles than of vacant plots. Property (‘house plus land’) values are thus more transparent than underlying land values. One measure of land value is property value minus the replacement cost of a similar building. If LVT were based on such a residual measure, the replacement cost could overestimate the value of the structure where deterioration through age has occurred, and hence underestimate the land value. 7 There could also be a misreporting incentive, by overstating the rebuilding cost to reduce tax, especially in high land-value locations.

However, superior hedonic mass-valuation measures can be applied to multi-year, cross-sectional house price data to extract land values (Diewert et al. 2021, 2015). 8 These exercises take account of the age of the building and other indicators of its condition. They also account for time variation in rebuilding costs as measured by construction price indices. These indices are largely national and not location-specific, helping in accurately separating land values from building values. Diewert et al. argue that, controlling in their models for common movements over time in national rebuilding costs, improves the identification of movements in building values relative to heterogeneous movements in local land values.

Phasing the transition to property tax reform: Six steps

The evolution from existing property tax systems to a green split-rate system in which land and buildings are subject to separate tax rates needs to be handled with care.

Step 1, where necessary, is to invest in the land registration system, which is not complete in all countries. Vacant and agricultural land is sometimes not covered by the prevailing property tax systems, whether for households or businesses, but should be, subject to tax allowances for lower per hectare valuations. Some countries could reconsider the harmonisation of local, regional, and national tax regimes and the funding structure of local government. Basic rules and valuations should be set at the national level, with limits on local tax-setting powers to prevent excessive tax competition between local governments.

Step 2 should be to invest, where necessary, in robust systems and trained staff for generating energy performance certificates.

Step 3 should be updating valuations to current market values, run concurrently with Steps 1 and 2. In many countries, valuations for the prevailing property tax are out of date (OECD 2022).

Step 4, given the new valuations, would be to announce new tax rates for residential property and businesses with green discounts. Introducing the simple equity-based deferral system for residential property, with small discounts for cash payers, is highly desirable as part of Step 4, as it prevents revaluation shocks to the cash-flow of those with limited ability to pay. Even with a deferral and the green discount, it makes sense to phase in the taxes paid. For example, in the first year, the effective property value for taxation could be based on one-third of the new value and two-thirds of the old. In the second year, the effective value could be two-thirds of the new and one-third of the old, with the transition completed in the third year.

Both simple deferral and the green discount are crucial elements in gaining public acceptability for property tax reform. As public alarm about the climate crisis mounts, especially among younger generations, the rationale for the green discount will be increasingly widely appreciated. Initially, deferral should be offered to the over-65 age group. Later, given experience with take-up and administration, deferral can be extended to all owners of residential property. Throughout, a programme of education and consultation to build public acceptance and achieve a degree of cross-party consensus would be highly advisable.

Step 5 should implement improvements in valuation systems with a view, for each property, to split the overall value into land and building components.

Finally, in Step 6, tax rates for the two components can be separated, with tax rates on land values adjusted upwards relative to tax rates on buildings.

Conclusion

It is urgent to implement green property taxes globally, given the climate emergency. This column has explained how to implement green discounts as part of good tax design. As well as incentivising the green transition and reducing climate risk for the financial system, the green LVT would broaden the tax base and increase revenue. It will improve equity, stabilise the economy and the financial system, improve efficiency in resource allocation and promote growth. It has the advantage of simplicity in implementation and low costs of administration. It will help reduce housing supply constraints. In country-by-country implementation of the green LVT, localism – i.e. subsidiarity and democratic accountability – and national objectives will need to be balanced to achieve public acceptability and ease the transition from the prior property tax system.

Source : VOXeu