Indonesia’s history, size, location, demographics, and resource endowments suggest that it should be an international trading powerhouse. Yet, evidence indicates that trade as an engine of economic growth has not been fully tapped .

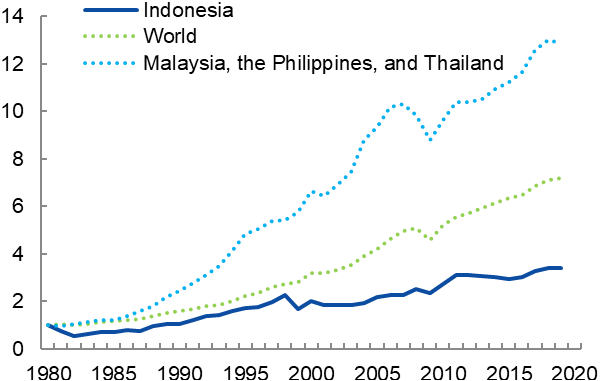

Supported by a steep decline in trade costs, advances in information technology, the liberalization of trade, and the expansion of global value chains, the volume of world exports increased by a factor of more than seven between 1980 and 2019. The volume of exports of regional peers such as Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand increased even more rapidly, rising by a factor of 13. In stark contrast, Indonesia’s exports rose by a factor of just 3.5 over this period (figure 1).

Figure 1 Indonesia’s exports of goods and services lagged behind the unprecedented expansion of global and regional exports since 1980

Index of volume of exports (1980 = 1)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators; IMF World Economic Outlook.

After the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis, Indonesia’s trade openness (exports and imports as a share of GDP) fell by more than half, coinciding with a period of deindustrialization. Its trade to GDP ratio fell from 72 percent in 2000 to 33 percent in 2020 and it is now the lowest among its regional peers. The contribution of manufacturing to GDP also declined significantly, falling from its peak of 31 percent in 2002 to 19 percent in 2021 (figure 2). In turn, the decline in trade openness has been limiting the contribution of trade to income growth given that global evidence suggests that a 1 percentage point increase in the ratio of trade to GDP increases income per capita by at least 0.5 percent (Frankel and Romer 1999).

Figure 2 The decline in the trade to GDP ratio in Indonesia coincided with a fall in the share of manufacturing over the past 20 years

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators.

Inward-looking trade policies have contributed to Indonesia’s weak trade outcomes:

- Tariffs declined, but they were offset by an increase in non-tariff measures (NTMs). The result has been a much less transparent trade policy framework and much less trade. Unnecessary and burdensome NTMs in the form of import approvals, mandatory certification with national standards, and restrictions on port of entry have led to efficiency and productivity losses for Indonesian businesses. These also have an adverse effect on exports, households, and investment decisions. Despite recent progress on reducing the incidence of NTMs such as pre-shipment inspections, these measures continue to impose a significant burden on Indonesian businesses—more burdensome than in other countries in the region.

- Indonesia’s restrictions on services trade are among the highest in the world, despite recent reforms. The Omnibus Law on Job Creation removed key barriers to foreign direct investment and relaxed restrictions on the movement of foreign workers. Additional reforms are needed, however, to realize the full potential of Indonesia’s services sector.

- Reforms are also needed to reduce the time, costs, and uncertainty of cross-border transactions.

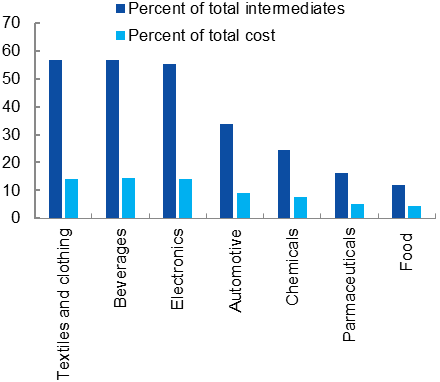

Looking ahead, policies to achieve the government’s import substitution objective (35 percent in 2022) would significantly disrupt domestic manufacturing and investment. Imports are essential for the Indonesian economy, for domestic value addition, investment, and exports, especially in higher value-added manufacturing and priority sectors (figure 3). Almost two-thirds of Indonesian exports are generated by firms that both export and import. These firms are more productive, export more frequently, and to more destinations than firms engaged in exporting activities alone (Cali et al. 2022).

Figure 3 Imports are a crucial input in production

Source: Statistics Indonesia.

As it charts a path forward, Indonesia has significant scope to build on its comparative advantages to boost export growth and diversification. Its enormous trading potential, combined with major structural shifts in the international trading system, present it with significant opportunities. Among the structural forces that could favor Indonesia are the post-COVID-19 reconfiguration of global value chains, the relocation of labor-intensive manufacturing away from China, and the global transition to a low-carbon economy.

An enabling trade policy framework could play a critical role in helping Indonesia boost exports and competitiveness, supporting the government’s objective of becoming a high-income country by 2045. As outlined in the December 2022 Indonesia Economic Prospects report, targeted reforms are needed (figure 4). Among the most essential are the following:

- streamlining and eliminating unnecessary NTMs

- removing barriers to services trade

- deepening and expanding the number of trade agreements

- improving logistics and trade facilitation

- aligning trade policies with green development.

While promoting economic growth and prosperity, trade liberalization will create winners and losers. Domestic policies to address inequalities and trade-related adjustments are key to ensuring that the gains from trade are equitably distributed. Trade reforms combined with such policies are critical to unleashing the benefits of trade for economic growth and the well-being of the Indonesian people.

Figure 4 Indonesia needs an enabling trade policy framework

Source : World Bank