How can the euro area’s return to fiscal sustainability be organised in view of soaring debt levels and the sovereign debt crisis? How can debts be financed efficiently, not least to prevent debt crises in weaker countries where high debt levels compounded by a hike in risk premiums on government bonds can create a debt trap? This looks like a classic dilemma. European solidarity with the most vulnerable European Union countries runs the risk of further weakening the incentives for individual countries to pursue fiscally sustainable policies.

While not a quick fix, our Blue Bond proposal charts an incentive-driven and durable way out of this dilemma, while helping prepare the ground for the rise of the euro as an important reserve currency, which could reduce borrowing costs for everybody involved.

Blue Bonds: EU countries should pool up to 60 percent of GDP of their national debt under joint and several liability as senior sovereign debt, thereby reducing the borrowing cost for that part of the debt.

Red debt: any national debt beyond a country’s Blue Bond allocation should be issued as national and junior debt with sound procedures for an orderly default, thus increasing the marginal cost of public borrowing and helping to enhance fiscal discipline.

Independent Stability Council (ISC): Blue Bond allocations to member states are to be proposed by an ISC and voted on by member-state parliaments in order to safeguard fiscal responsibility.

1 Introduction

The sovereign bond crisis in the euro area calls for both lower and higher sovereign bond yields. Lower yields are desirable because they would reduce the cost of financing government debt for European taxpayers. This is particularly relevant in the years ahead, when the financing of the accumulated debt will remain a serious burden even once deficits have come back to sustainable levels. And higher bond yields are desirable as an early warning signal to those countries on an unsustainable fiscal path. If financial markets are failing Greece now, they failed Greece even more before the crisis by continuing to provide cheap funding while fiscal policy was reckless.

Achieving both higher and lower yields at the same time would appear to be impossible. Yet, in this Policy Brief we argue that our Blue Bond proposal can do just that. Before explaining what it is, let us first explore how the two objectives might be pursued separately.

The cost of borrowing could be lowered significantly by pooling government debt within the euro area, creating a euro bond. The yield of that euro bond would likely be lower than the weighted average of national bond yields. The euro bond would become a highly liquid asset with a volume of available debt rivalling the extremely successful US Treasury bond. This would help the euro’s rise as a second global reserve currency.

Conversely, the cost of borrowing should be increased for a country on a reckless borrowing path by disentangling sovereign debt responsibilities within the euro area to the extent that the no-bailout clause becomes credible not only de jure (which it is) but also de facto, which presently is not the case as recent events show. Currently, euro-area members have collectively come to agree that the political and economic cost of not at least attempting to bail out Greece is so enormous that it would be irresponsible not to try. The reason is that in the present setting any sovereign default is likely to have systemic consequences. To avoid these, it needs to be credibly established that sovereign bankruptcy for members of the euro area is something that has been properly planned for rather than something that threatens the very existence of the euro area. Such advance planning needs to concern the bankruptcy procedure itself and needs to reduce the vulnerability of the European banking system to a sovereign-debt crisis. Also, the risk of contagion within the euro area needs to be brought under better control.

In a nutshell: cheaper borrowing requires more integration whereas more expensive borrowing requires measures to avoid systemic consequences. On that basis, we now try to pursue both objectives at the same time by pooling one part of the debt while ringfencing another part.

Specifically, we propose that eligible EU governments should pool up to 60 percent of GDP of their government debt in the form of a common European government bond, which we call the Blue Bond. Any public debt in excess of their Blue Bond allocation national governments would have to issue in junior national debt, which we will call the red debt in the remainder of this paper.

Section 2 outlines the basic economics of the proposal. In section 3, the impact of greater liquidity in the Blue Bond on borrowing cost is discussed. In section 4, suitable institutional underpinnings of our proposal are explored and a transition regime is proposed. Finally, in section 5, the likely implications of our proposal for different types of participating countries are explored.

2 The basic economics of the Blue Bond

A country’s total borrowing costs can be calculated as the product of the stock of outstanding debt times the average interest rate to be paid on that debt stock, as Figure 1 shows.

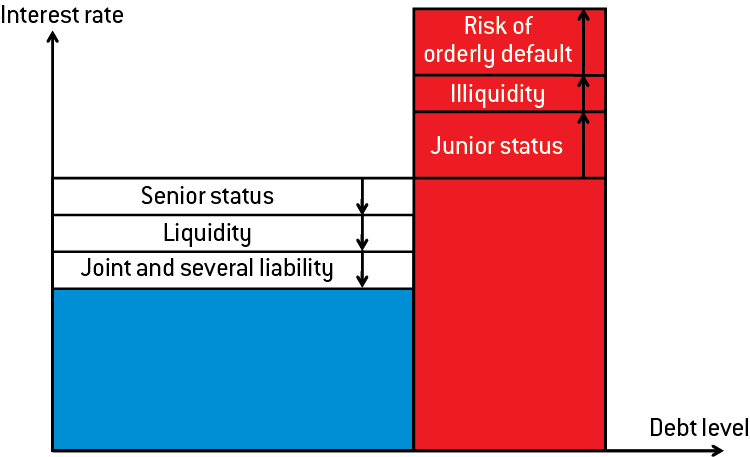

We propose that this essentially homogenous government debt should be broken down into two tranches: a senior (‘blue’) tranche up to a certain debt threshold which we assume to be 60 percent of GDP in the following; and a junior (‘red’) tranche for any additional debt above that threshold. In case of a partial default, the red tranche will be hit first and the blue tranche will only be affected by that part of the default (if any) that is not absorbed by the junior tranche. In other words, any government funds used to service and repay government debt will always first be used to satisfy the claims of the Blue Bond holders.

As a result, the blue tranche will become less risky than the status-quo debt, and the red tranche will be riskier, leading to a differentiation in interest rates (Figure 2).

This rate differentiation is reinforced by liquidity effects. Under our proposal, all the countries participating in the Blue Bond would pool and merge their blue tranches, creating a government bond market similar in size, liquidity and quality to the US Treasury debt market. Due to this gain in liquidity, the cost of borrowing would be further reduced on the blue tranche. By contrast, the liquidity of the red tranche would be substantially less than the liquidity of homogeneous national bonds currently. This reduced liquidity should further increase borrowing costs on the red debt.

Figure 1: Borrowing cost in the status quo

Source: Bruegel.

Figure 2: Key factors that influence the cost of borrowing in the senior (blue) and junior (red) tranche

Source: Bruegel.

There are additional risk considerations that should be borne in mind. For the blue debt we propose joint and several liability to ensure that a triple A asset is created. From an investor’s perspective, joint and several liability will reduce the risk of the asset further because default risks tend not to be perfectly correlated. Therefore, the blue debt cost of borrowing in the average euro-area country should be lower still.

By contrast, defaulting on the entire red tranche would be less disruptive, because in this eventuality, the borrowing capacity in the senior tranche would not be destroyed. From an investor’s perspective, the prospect of a less-disruptive default on the junior tranche increases the risk of default, thereby calling for an additional risk premium (see eg Jochimsen and Konrad, 2006).

To ensure the credible prospect of an orderly default on the red debt, the preparations for such an eventuality need to be thought of as an integral part of euro-area procedures. Tightened European supervision of banks and rating agencies would need to ensure that the financial sector does not become vulnerable to a default on the red debt by fiscally less-robust member states. Among others, the European Central Bank (ECB) should take a prudent stand regarding the eligibility of red bonds for its repo facility. Furthermore, in order to qualify for pooled borrowing via the Blue Bond, national governments should be obliged to introduce a standardised collective-action clause for their red bond borrowing, which would make any debt restructuring a less messy and lengthy undertaking.

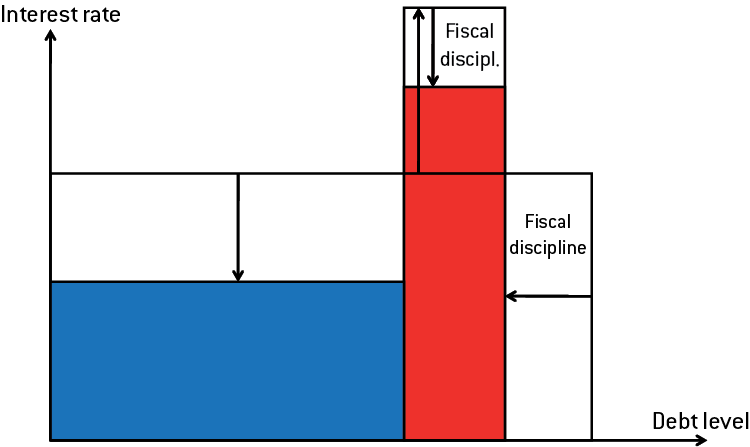

Finally, we need to add to the picture a key aspect that we have neglected so far: the likely impact of our proposal on overall debt. Generally, one would expect fiscal discipline to improve as a result of the increased cost of public-sector borrowing at the margin (Figure 3). Improved fiscal discipline would not only bring down overall debt, but would also reduce the cost of borrowing on the red tranche substantially compared to Figure 2, which assumes unchanged borrowing levels.

Figure 3: Improved fiscal discipline due to the increased marginal cost of debt

Source: Bruegel.

Ultimately, this disciplining effect of the higher marginal cost of borrowing is the most important distinction between our Blue Bond proposal and the first generation of proposals to pool the debt of EU countries in a euro bond (see eg Bonnevay, 2010, or the concerns voiced by Issing, 20091). Together with the liquidity effect of the senior tranche, it is the fiscal-discipline effect of the junior tranche that would ensure that the average cost of borrowing would decrease compared to the current situation.

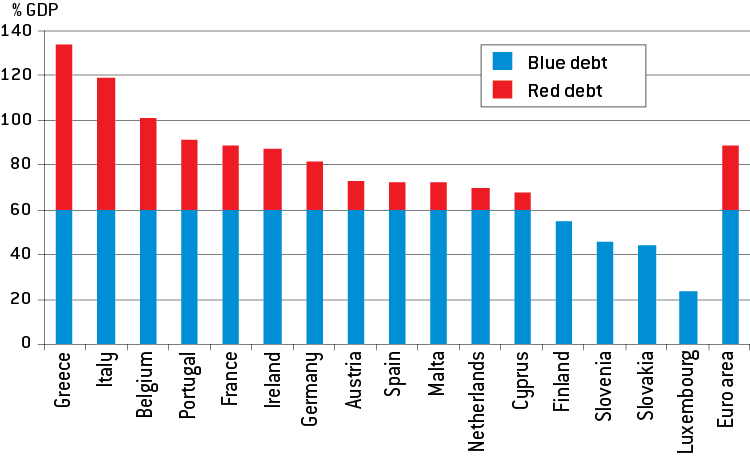

Clearly, the proportions of blue and red debt would vary substantially from country to country as illustrated by Figure 4, and so will the nature of the benefits implied by the proposed scheme, as discussed in the closing section.

Figure 4: Split of 2011 forecast debt levels into red/blue debt

Source: Bruegel based on DG ECFIN. Note: Forecast levels of debt as % of GDP.

3 The impact of liquidity on borrowing costs

The euro-area Blue Bond market could amount to 60 percent of euro-area GDP (about €5,600 billion), which is about five times the current market for the German Bund and almost as large as the US Treasury debt market (about $8,300 billion).

All other things being equal, greater liquidity in a bond reduces the borrowing costs (see Amihud et al, 2005, for the various measures of liquidity). Large public institutional investors (central banks and sovereign wealth funds) greatly value liquidity. For instance, many Asian central banks buy almost only German Bunds and French government debt, because they are required to invest only in particularly safe and liquid fixed income assets.

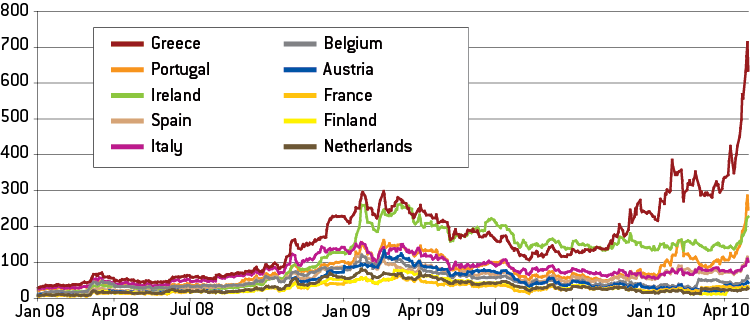

In practice it can be difficult to separate yield differences on account of liquidity, from yield differences on account of risk. To illustrate the problem, it is instructive to look at the recent surge in sovereign-bond spreads in the euro area (Figure 5). This increase is partly due to a flight to liquidity and partly due to a flight to safety, with investors prepared to pay more for a given level of liquidity or safety. But, in addition, the crisis has also changed objective levels of liquidity and the risk of default for assets. Disentangling these four reasons for changing yields is anything but straightforward.

Figure 5: Sovereign bond spreads over the German Bund in the euro area

Source: Bruegel based on Thomson Datastream, Eurostat.

Finally, the dynamics of a self-fulfilling prophecy could be at work, with weaker countries suffering from expanding spreads, which can in turn further weaken their fiscal outlook.

By creating a liquid asset such as the Blue Bond, one could hope to reap a moderate liquidity premium in normal times and a much more substantial liquidity premium in times of crisis. This increased liquidity premium for the Blue Bond in times of crisis is of particular interest because it would increase the resilience in a crisis of government borrowing, not least of smaller and weaker economies.

Furthermore, the introduction of a Blue Bond with liquidity on a par with US Treasury bonds could help to promote the more widespread use of the euro as a reserve currency. Increased demand for Blue Bonds by central banks and sovereign wealth funds, not least in China and other Asian countries, would increase the liquidity gains further. The reserve-currency effect could be significant: Gourinchas and Rey (2007) estimated that, thanks to its reserve currency status, the US has been able to borrow at reduced rates for the last 50 years by providing international investors, including central banks, with a large, safe and ultra-liquid pool of debt.

For a back-of-the-envelope calculation, let us cautiously assume a 30 basis-point liquidity premium3 over the average of participating countries, and also averaging across times of calm and times of crisis in financial markets.

With the long-run average real interest rate of government bonds in the euro area at around 300 basis points, a 30 basis-point reduction of borrowing costs would reduce the interest burden by an average of 10 percent at any point in time. It turns out that this is equivalent to reducing the net present value of the debt stock by 10 percent also. Thus, assuming a legacy debt stock of 60 percent of GDP, the liquidity advantage generated could amount to an average net present value of six percent of the GDP of participating countries.

While this number is of course subject to considerable uncertainty, it illustrates the non-negligible scale of the liquidity gain that one could hope to generate. It is worth noting that, by the same token, it may be possible for individual member states to reap additional savings by pooling borrowing that is presently fragmented between various state agencies, regional and local governments. In the spirit of our proposal, this could even be achieved without substantially reducing the autonomy of these different state actors.

4 Institutional set up

Returning to the European level, it is of course not enough to find that a substantial economic gain could be reaped by pooling liquidity. In order to realise the gain, its distribution between member states would have to be calibrated appropriately to ensure that the countries involved feel it is in their best interests to participate. One possibility would be to introduce differentiated membership fees for countries issuing Blue Bonds, with fiscally stronger countries paying lower fees than fiscally weaker countries, as proposed by De Grauwe and Moesen (2009). However, such pricing would to some extent be arbitrary since the different national yields for red debt will only ever be a rather imperfect proxy for the risk of default on the senior debt. Also, as a general rule, it is politically difficult in the EU to organise explicit redistribution from weaker to stronger countries, even if the total effect, taking the lower debt-refinancing costs into account, would also remain positive for weaker countries.

Instead, we favour an approach that uses the Blue Bond rent as an incentive for countries with high debt levels to become more disciplined fiscally in the aftermath of the crisis. This would be in the interest of the weaker countries themselves, but could also provide substantial benefits to stronger countries, because it would help re-establish the credibility of the Stability and Growth Pact and would reduce the risk that a bail-out of weaker countries might become necessary.

To strengthen fiscal discipline, we propose a differentiated allocation of Blue Bond borrowing quotas by country. Those countries with credible fiscal policies should be allowed to borrow up to the full 60 percent of GDP, while countries with a weaker fiscal position would only be able to borrow a lower proportion of GDP in Blue Bonds. In the extreme, if a participating country were consistently to pursue unsustainable fiscal policies, this mechanism would even allow for a gradual eviction from the scheme by means of an ever-shrinking Blue Bond allocation.

When borrowing in red debt becomes expensive for a country, the temptation to find cheaper ways of borrowing on the side can become very strong. Typically, this would involve some form of financial engineering to borrow against specific future revenues. To prevent the emergence of such ‘black debt,’ all countries participating in the Blue Bond scheme would need to enter an agreement voiding any special collateral offered for black debt, thereby automatically converting it into red debt.

But would the Blue Bond scheme be compatible with the no-bailout clause in Article 125 of the EU Treaty? In economic substance, we argue that it would, because the joint and several guarantee would at most apply to senior debt amounting (up) to 60 percent of GDP, which is a debt level deemed sustainable for any EU member state, according to the Maastricht Treaty. Therefore, the guarantee would not apply to debt crises caused by unsustainable fiscal policies leading to excessively high debt levels. To the extent that situations where debt-to-GDP ratios of less than 60 percent are only unsustainable in exceptional situations (Article 100 of the Treaty), such as natural disasters when a bailout would be allowed, a legal conflict would not arise. This differentiates the Blue Bond from more radical proposals to pool the entirety of the EU’s public debt, in which case changes to the spirit if not the letter of the treaty would appear unavoidable.

Next, the question arises of who should be in charge of the allocation of Blue Bonds? Since each Blue Bond implies a guarantee by all the participating nations and their taxpayers, the ultimate decision on the allocation of Blue Bonds and their corresponding guarantees will have to be taken by the national parliaments of all the participating countries.

So that there will be an orderly and stable process for preparing these parliamentary decisions, we propose that participating countries establish an Independent Stability Council (ISC) with the responsibility annually to propose an allocation for the Blue Bond, in effect amounting to a take-it-or-leave-it offer. The fiscal credibility of this council would be key to establishing financial markets’ trust in the Blue Bond, as the historical experience of the Australian Loan Council suggests. In order to be admitted to the Blue Bond scheme, countries would have to convince the ISC that their fiscal policy is credible enough to be insured (via the joint and several liability) by the most credible countries of the euro area. For example, one could imagine that a country would not be allowed into the Blue Bond pool if it did not have a binding fiscal rule, analogous to the one inserted by Germany into its constitution.

A secretariat with the necessary economic and fiscal expertise would support the Stability Council. Once the council has made a proposal, it would be voted on by the national parliaments of all participating countries. Failure to adopt the proposal would simply lead to a leave of absence of the country in question from the Blue Bond scheme, during which no new Blue Bonds could be issued and no new guarantees for the Blue Bonds of other countries would be provided. An absence over several years would thereby lead to a gradual exit from the scheme. However, since the decision of any major participating country to ease itself out could undermine confidence in the entire scheme, the ISC would have a strong incentive to err on the side of caution, thereby safeguarding the interests of the European taxpayer.

An inevitably delicate question is how to best handle the transition to the Blue Bond scheme. We favour an approach where all the legacy government debt (ie issued before the beginning of the Blue Bond scheme) is treated as senior to the red debt but junior (one way or the other) to the blue debt. This legacy debt would then be gradually replaced by the senior blue debt and the junior red debt as the existing debt stock is rolled over. For each country, the annual Blue Bond allocation would determine which proportion of the debt could be issued as Blue Bonds and which would have to be issued as more costly red debt. Since most countries commonly issue bonds with maturities of 10 years but usually not more, the transition should in effect be completed after a decade.

However, other more generous and more rapid transition scenarios are conceivable, for example as part of a debt restructuring process that may become necessary during the current sovereign debt crisis.

5 Country perspectives

Even if our proposal achieves overall welfare gains, it is not a priori obvious if different countries would have an incentive to participate in this voluntary scheme. Therefore, we need to explore why different groups of countries could indeed benefit from the scheme. There are three important benefits.

First, smaller countries with relatively illiquid sovereign bonds stand to benefit more from the extra liquidity of the Blue Bond than larger countries. For example, Austria and Luxembourg would benefit more than France and Germany although even for Germany borrowing costs under the Blue Bond scheme might fall below current levels.

Second, countries with high debt-to-GDP ratios would have the strongest incentive for fiscal adjustment. For example, Greece and Portugal would have to undertake a greater effort than, say, Finland or the Netherlands to bring down borrowing costs in red debt through a strengthened commitment to fiscal discipline that is credible to market participants. We would expect that many countries with high debt levels may in fact welcome this opportunity to commit to stronger fiscal discipline after the present crisis. But some may not.

Third, countries that worry most about having to foot the bill for a sovereign bailout in the present crisis or in future crises stand to benefit most from the strengthened discipline of the Blue Bond scheme. However, this last observation crucially depends on the quality of the Blue Bond’s institutional set-up.

Overall, we are optimistic that it would be in the self-interest of a sufficient number of countries to participate in the proposed scheme, on the basis that institutional safeguards are robust.

Should the scheme go ahead, even countries that are hesitant about the additional fiscal discipline that participation in the scheme would entail may ultimately find it difficult to stay outside for the simple reason that markets could perceive a decision not to participate as a bad signal.

Source : Bruegel