Climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of flooding, but there is still little evidence on its short- and medium-term microeconomic impact. This column explores the effects of flood events on European firms. Water damages have a significant and persistent adverse effect on firm performance and may even lead to firm exit. However, frequent floods do not significantly worsen firm performance, suggesting that firms adapt in flood-prone areas. In such regions, economic activity may be reallocated from firms exposed to water damage to unaffected firms.

Floods have become more frequent and severe in recent decades. The trend is expected to continue due to long-term temperature increases and more extreme weather patterns caused by climate change. The associated economic costs are significant and rising. Flood-related economic losses in the EU already exceed €12 billion per year (European Environment Agency 2019). According to conservative estimates, exposing the EU economy to global warming of 3°C above pre-industrial levels would cost at least €175 billion per year, or 1.38% of the continent’s GDP (Feyen et al. 2020).

While the public debate emphasises the aggregate effects of increased flooding based on long-term climate scenarios, the evidence on the microeconomic impact of water damages is still limited and suggestive of mild effects over the short and medium term on businesses (Jia et al. 2022) and local economies (Roth Tran and Wilson 2020).

Some papers even indicate positive growth effects in the aftermath of flood episodes in Europe (Noth and Rehbein 2019, Leiter et al. 2009). Positive firm performance is interpreted as evidence that natural disasters that destroy physical capital give firms opportunities to update the capital stock and adopt new technologies. In this respect, floods act as ‘creative destruction’. Also, the emergence of new activity, for instance to boost prevention capacity, often has positive growth impacts.

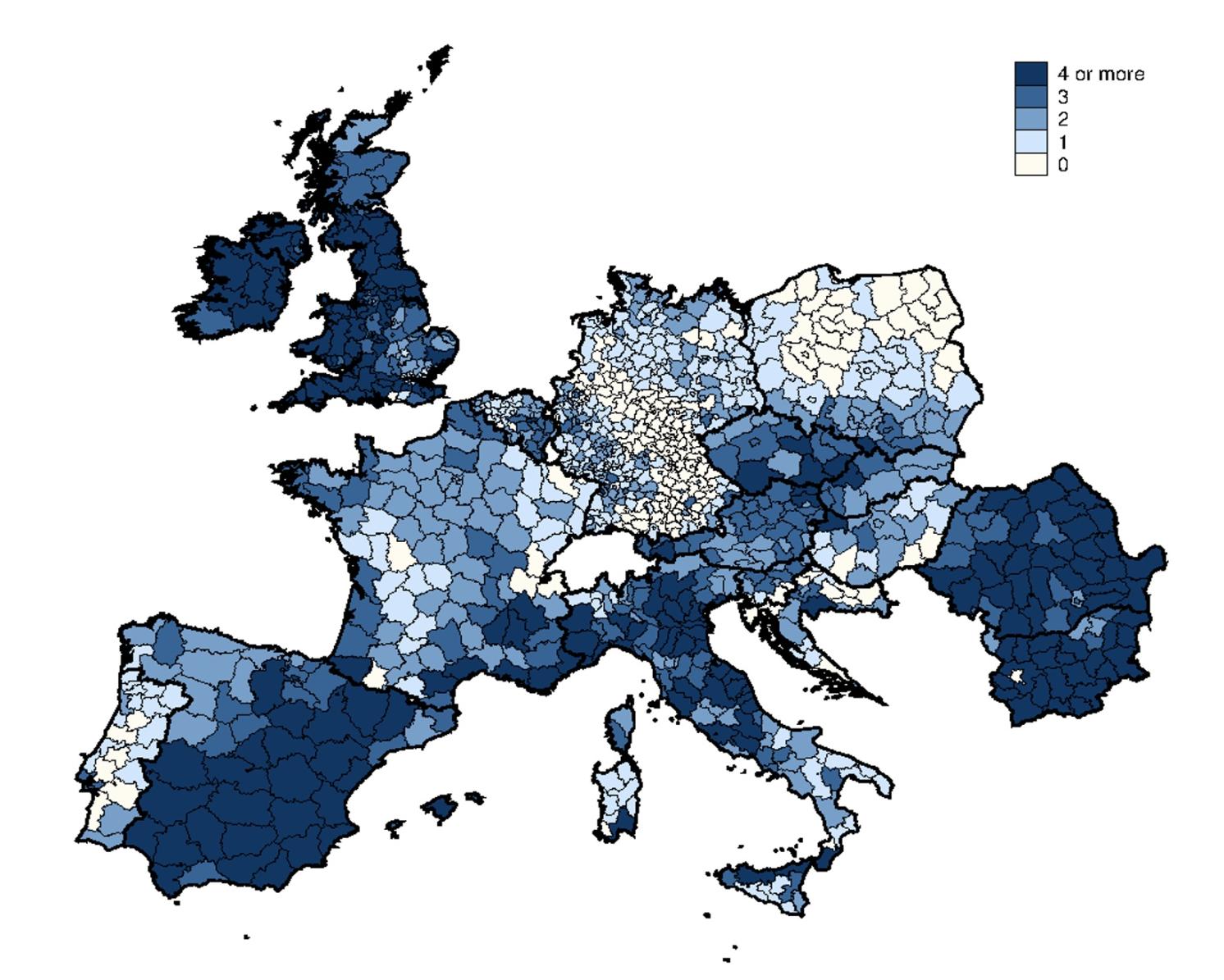

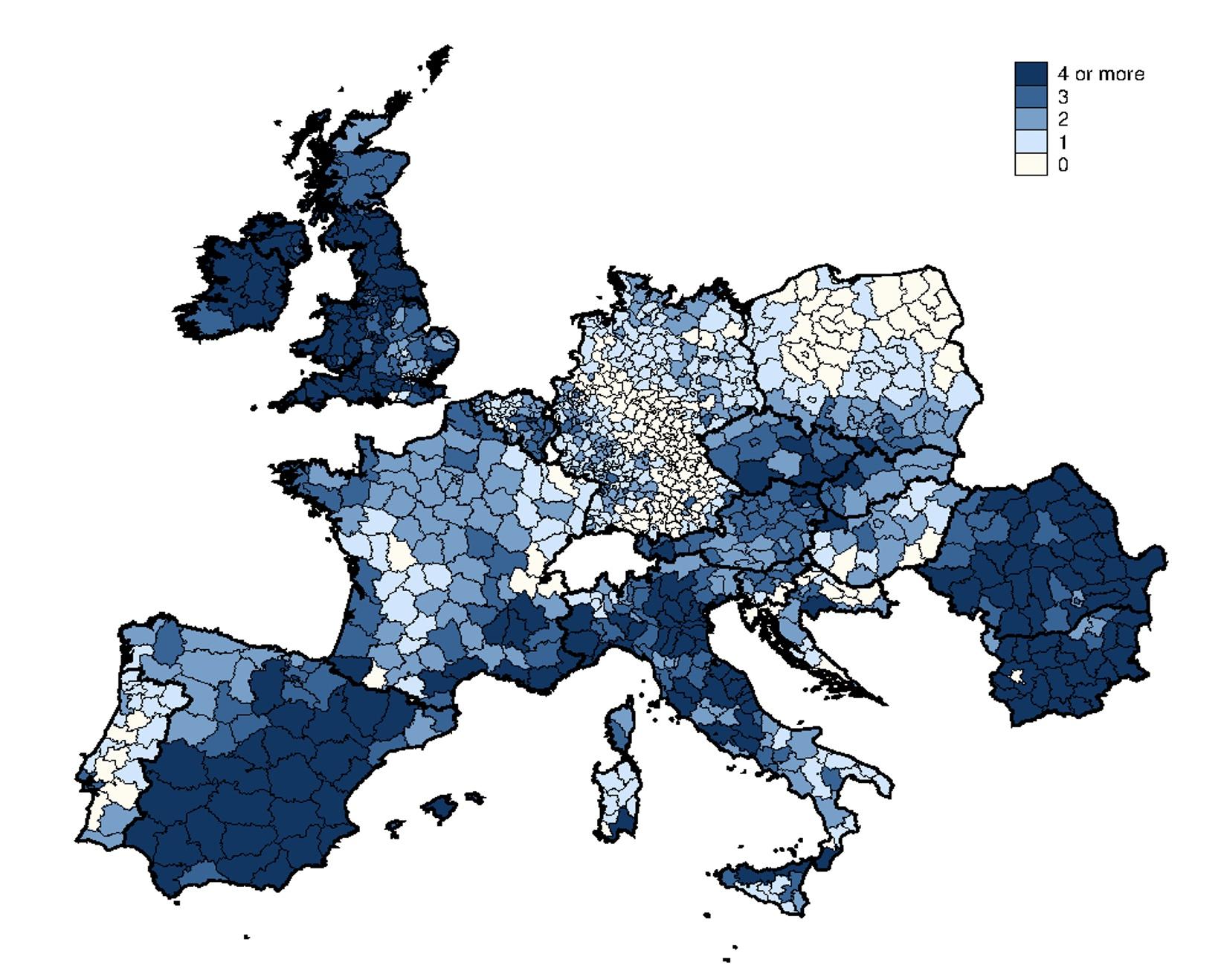

In recent research (Fatica et al. 2022), we investigate the dynamic impact of flooding on European manufacturing firms from 2007 to 2018. Between 2007 and 2018, approximately 78% of the EU Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics level-3 (NUTS3) regions were flooded at least once, and approximately two-thirds of the regions were flooded multiple times (see Figure 1). Floods strike EU NUTS3 regions every three years on average. Floods are so common in some regions that flooding is the norm rather than the exception.

Figure 1 Frequency of flood episodes

Notes: The figure depicts flood episodes in 2007–2018 by EU Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics level-3 (NUTS3) region. Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian and Baltic countries not included due to data availability.

The medium-term impact of floods

We disentangle flooded firms from firms unaffected by water damage in disaster regions by combining granular flood hazard maps and detailed information on firm geo-location (zip codes and geodetic coordinates) in a novel way. The unaffected firms are used as the control group.

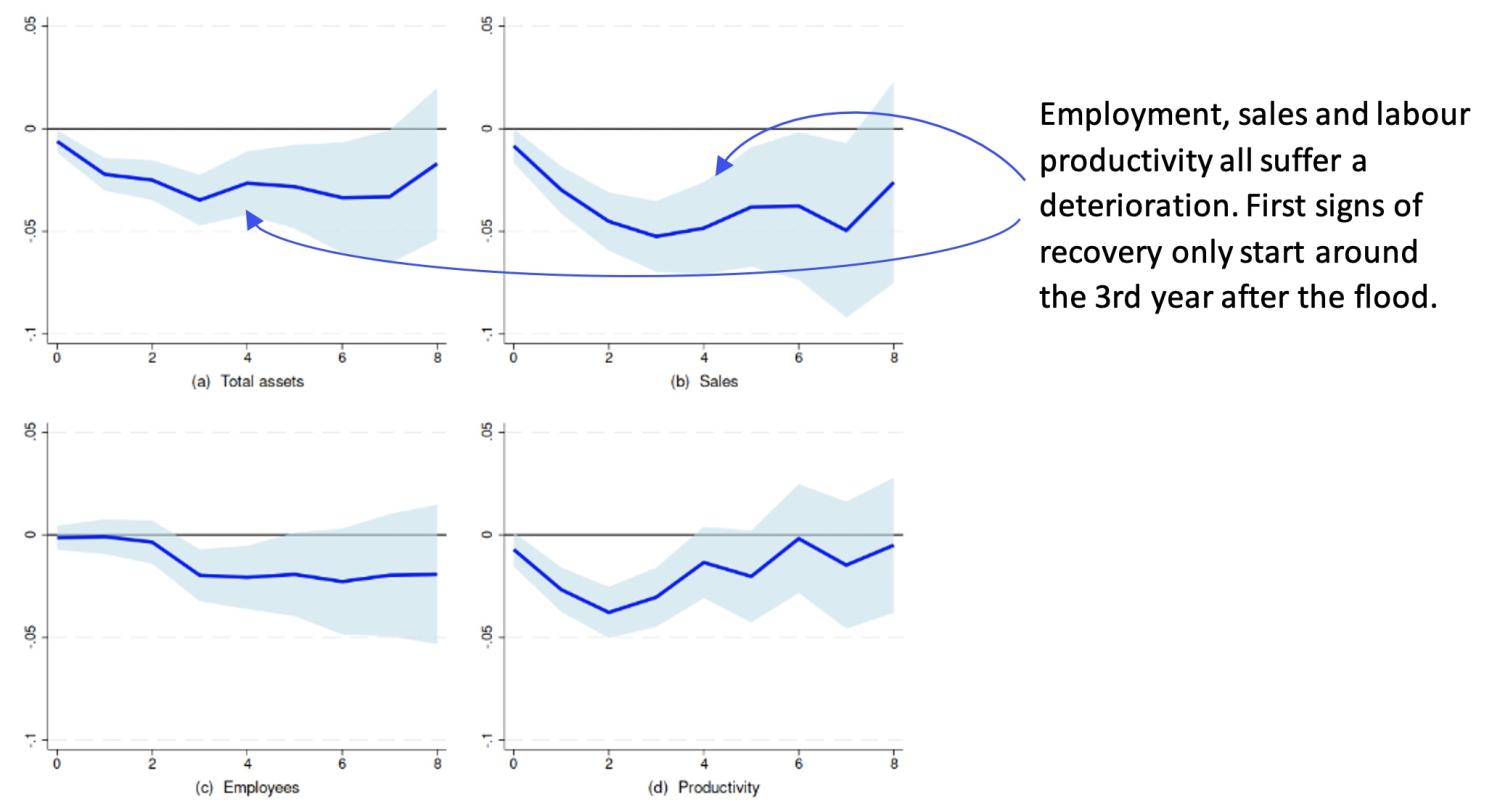

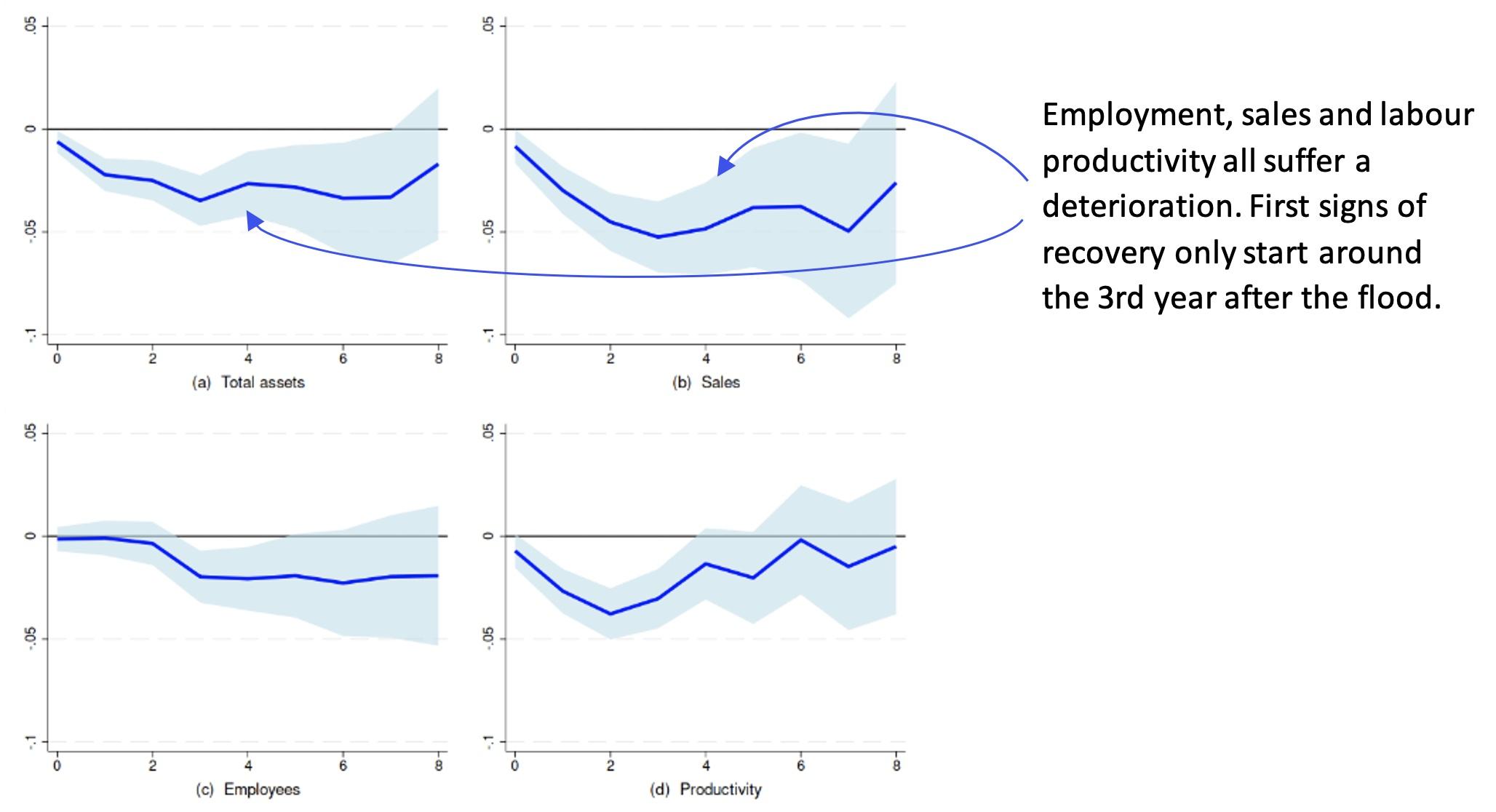

Water damage has a significant and long-term negative impact on firm performance. A typical flood depreciates a firm’s assets by about 2% in the year following the event and by up to 5% seven years later. Sales are 4.5% lower on average than they would have been in the no-disaster scenario. Employment – while adjusting more slowly – follows a similar pattern, with no clear signs of recovery over the medium term. Because of the worsened output performance and the sluggish reaction of employment, labour productivity – calculated as output per worker – also deteriorates in the short term, showing some signs of recovery around three years after the flood episode (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Dynamic impacts of floods on firm assets, sales, employees, and productivity

Notes: The figure displays the impulse response functions derived from estimating a local projection model on selected firm-level variables. The x-axis is the number of years after the flood episodes; the y-axis is the changes in the variables. The light blue areas are the associated 95% confidence intervals.

As expected, large-scale floods are more disruptive than milder ones. Compared to unexposed firms, firms hit by a major disaster experience a deterioration of total assets of around 4% one year after the event. By contrast, the asset damage for firms exposed to less severe flooding is around 1%.

Companies that experience repeated flooding are able to weather water damage better than those located in less-flood-prone areas, pointing to successful adaptation strategies being implemented. When leading to significant balance-sheet deterioration, floods may also affect firm survival. Exposed firms are, on average, less likely to remain operative a year after the disaster than non-exposed firms.

Reallocation and aggregate effects

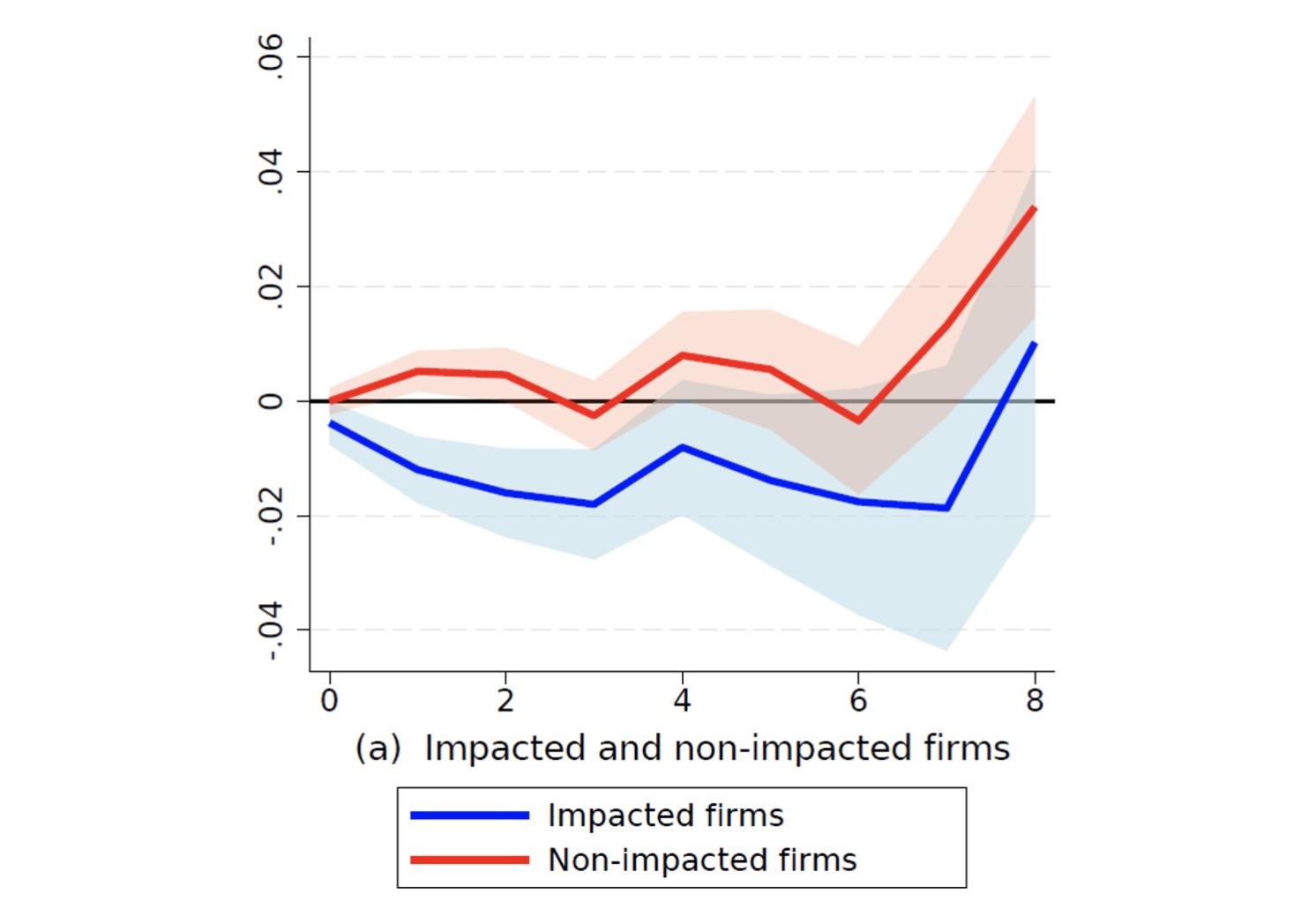

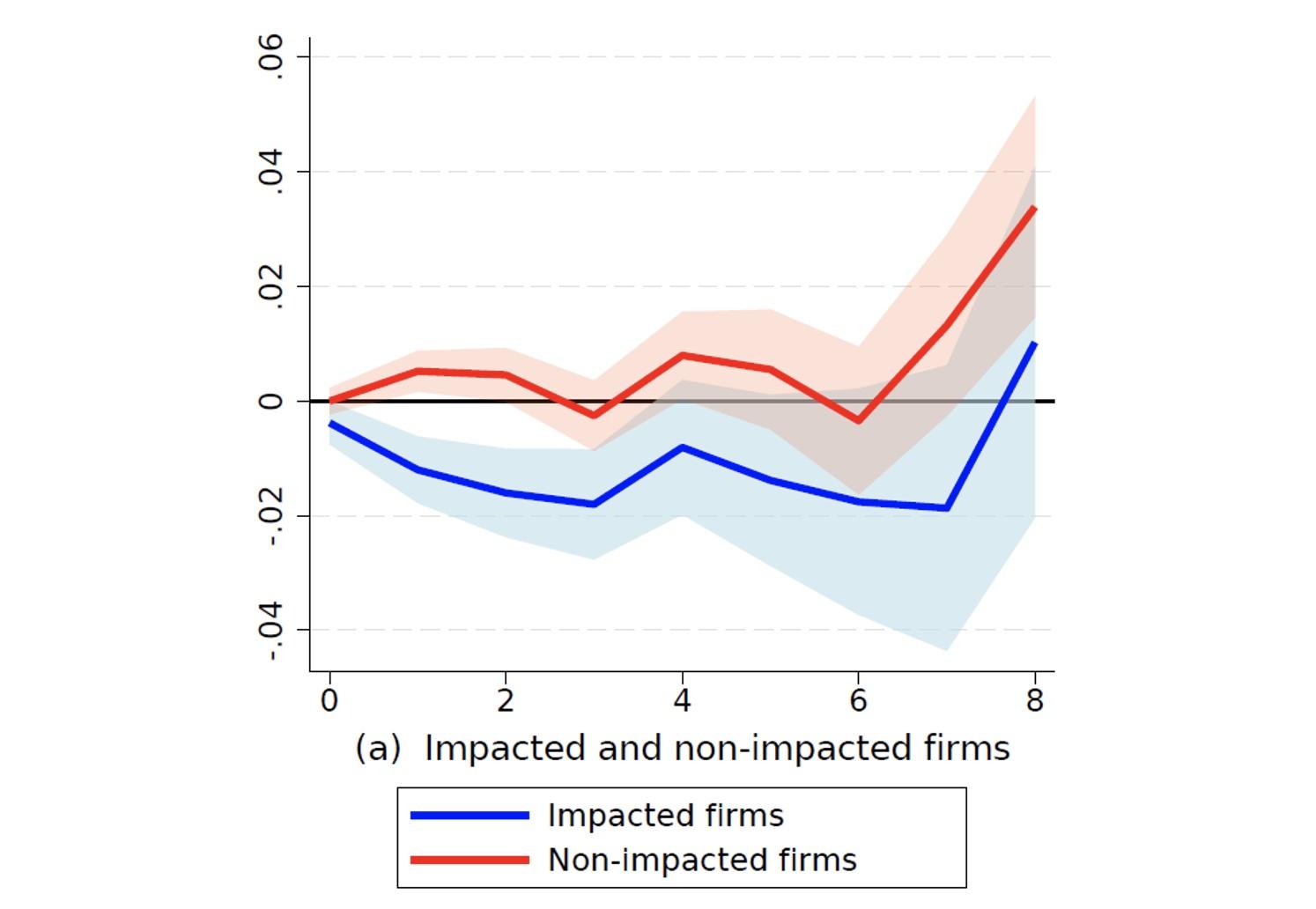

Overall, our results suggest that floods have disruptive consequences on the performance of affected firms. However, we find the opposite is true for firms in disaster-affected regions that are likely not directly impacted by water damage – because they are located farther from flood-prone areas: they show positive post-flood performance (Figure 3). We take this as suggestive of ‘reallocation’ of economic activity in disaster regions, from deluged firms towards firms shielded from direct water damage.

Figure 3 Impact on firms in flooded regions

Notes: The figure displays the impulse responses derived from the local projections for the firm’s total assets. The estimated impulse responses are depicted for firms directly impacted by the flood (blue line) and for firms in the same NUTS3 region that are not directly exposed to water damage (red line)

When we look at aggregate variables, we find a positive trend for comparable outcomes at the regional level. However, our granular evidence suggests caution in interpreting these results, as they hide important composition effects. The net effect of reallocating economic activity from affected to unaffected firms in the same region may result in positive aggregate dynamics, leading to conclusions about the impact of the floods that cannot be extrapolated to a more granular level.

Conclusions

As the frequency and severity of flood events and their associated economic, social, and environmental costs are expected to increase in the coming decades, assessing their impact is of paramount importance, especially so that private-sector policies and schemes can be designed to boost the resilience of affected economic agents and local communities.

Strengthening adaptive capacity and minimising vulnerability to climate impacts requires a better understanding of how behaviour and economic activity are affected by natural disasters. We provide novel evidence on the destruction and reallocation of European businesses brought about by floods. Our analysis points to the need to consider microeconomic-level adjustments in evaluating the consequences of natural disasters.

Source : Reuters