Wealth disparities among hunter-gatherers and farmers in Neolithic western Eurasia (11,700 to 5,300 years ago) were less substantial than the inequalities of the past five millennia, owing to a culture of ‘aggressive egalitarianism’ that thwarted the emergence of enduring wealth inequality. This column argues that the Late Neolithic introduction of the ox-drawn plough raised the value of material wealth relative to labour, while a concentration of elite power in early proto states (and eventually the exploitation of enslaved labour) provided the political and economic conditions for heightened wealth inequalities to endure.

What can the prehistoric origins of enduring wealth inequality tell us about changes in technology, institutions, and culture as drivers of economic inequality today and the likely trajectory of wealth disparities in the future? The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is ‘quite a lot’.

Prehistory provides a treasure trove of new information not found in most of the empirical literature, which is based on income and wealth taxation data available only over the last couple of centuries (Atkinson and Piketty 2007, Kohler and Thompson 2022). Here we exploit a feature of prehistoric and ancient evidence that is particularly valuable for the study of inequality: the range of institutions, technologies, and cultures that humans experienced over this long period is vastly wider than in more recent societies.

Thus, the prehistoric record allows us to study the effects of radical changes along three dimensions: technology (e.g. from collecting food to producing it and on to the substitution of draft animals for human labour); institutions (e.g. from decentralised polities without formalised political leadership to governance by states and enslaved labour); and cultures (e.g. from egalitarian, collective, and reciprocal norms to individualism, markets, and limited families).

In two related papers, we extend our series to the year 2000, including a revision of current understandings of ‘the little divergence’ in medieval and early modern Europe based on our wealth inequality data. And we explicitly measure the degree of uncertainty associated with our estimates; for each site and date, we provide a probability distribution of likely values of the Gini coefficient (Fochesato and Bowles 2024a, b).

The inequality revolution in prehistory

In Figure 1, we present our estimates of inequality in material wealth for western Eurasia from the end of the Palaeolithic – almost twelve millennia ago – to the end of the Roman Empire, a millennium and a half ago (Bowles and Fochesato 2024). The estimates are based on the size of dwellings, the size of storage areas (where these can be identified), land ownership, and the value of goods buried with the dead. Gini coefficients (denoted G, with 0 indicating perfect equality and 1 indicating maximal inequality) based on these measures have been calculated (insofar as is possible) to be comparable across sites and dates. This has entailed adjustments with respect to the above four asset types (for example, ‘grave goods’ in a given population are typically more unequally distributed than dwelling size) and wealth holding unit (we infer household wealth from individual grave goods by creating hypothetical male-female pairings). We have also corrected for biases due to both small sample size and the fact that the populations from which our samples are drawn differ in size and geographical scale. Finally, we adjust for the common absence from data sets on wealth holdings of those without wealth (for example, landless or enslaved peoples).

Our account based on these data addresses what we consider two gaps in the literature. The first is the puzzle of how societies limited the development of wealth inequalities in the four millennia following a change in technology with the potential for much greater inequality – that is, the emergence of farming. The second is the lack of a convincing explanation as to how these heavily armed populations that had been committed to egalitarian norms would, at least two millennia prior to the appearance of even proto states, succumb to the imposition of wealth inequality that quickly rose to substantial levels and then persisted over centuries

Accounting for enduring wealth inequality: technology, culture, and institutions

First, as is clear from Figure 1, wealth inequality in our data set remained modest for at least four millennia following the agricultural revolution (beginning around nine millennia BCE), putting to rest the common idea that it was farming per se that ushered in enduring substantial wealth inequality.

But second, farming did contribute to the eventual potential for greatly enhanced inequality. Beginning early in the Neolithic, sedentary living – along with harvesting and then cultivating storable cereals and eventually raising large animals – provided opportunities for private ownership of an increased portion of the sources of a household’s livelihood. This correspondingly reduced the importance of sources of income that were generally available independently of parental wealth (Bowles and Choi 2019).

Figure 1 Inequality in material wealth in western Eurasia from the end of the Palaeolithic to the Roman Empire

Notes: Dates on the horizontal axis are years before the Common Era (BCE). PPNA and PPNB refer to the western Asian Pre-Pottery Neolithic periods A and B periodisation used by archaeologists. Our database consists of 185 estimates of the Gini coefficient (including three from the late Palaeolithic, not shown in this figure). To put these data in the perspective of contemporary levels of wealth inequality, the line labelled G = 0.695 indicates the mean of 20 estimates of wealth inequality for the year 2000 (Davies et al. 2008), CI (0.666; 0.724). The mean of the 85 estimates shown since 4000 BCE is 0.677 [0.472; 0.930]. The line labelled G = 0.362 indicates the mean (CI 0.336; 0.387) of the 100 estimates in this database prior to 4000 BCE.

Moreover, the increasingly storable nature of the goods making up a family’s livelihood, along with private ownership of stores, allowed the more successful households to withdraw from community-based risk-mitigation practices by means of private storage, reducing the extent of egalitarian redistribution. Compared to the large portfolio of species on which hunter-gatherers depended, farmers’ reliance on a small set of domesticated plants and animals (living in close proximity) made them more vulnerable to wealth shocks (e.g. due to disease), contributing to wealth inequality.

Third, despite these developments prior to the Bronze Age, aside from exceptional and typically ephemeral ecological conditions, substantial levels of inequality did not endure, due in part to what the archaeologist Ian Hodder termed the “aggressively egalitarian” nature of some Neolithic communities (Hodder 2014), whose customs included egalitarian social norms and cultural practices such as widespread sharing of food (Bogaard et al. 2009) and the likely deliberate destruction of heritable wealth (Halstead 2019, Twiss et al. 2008, Wright 2014).

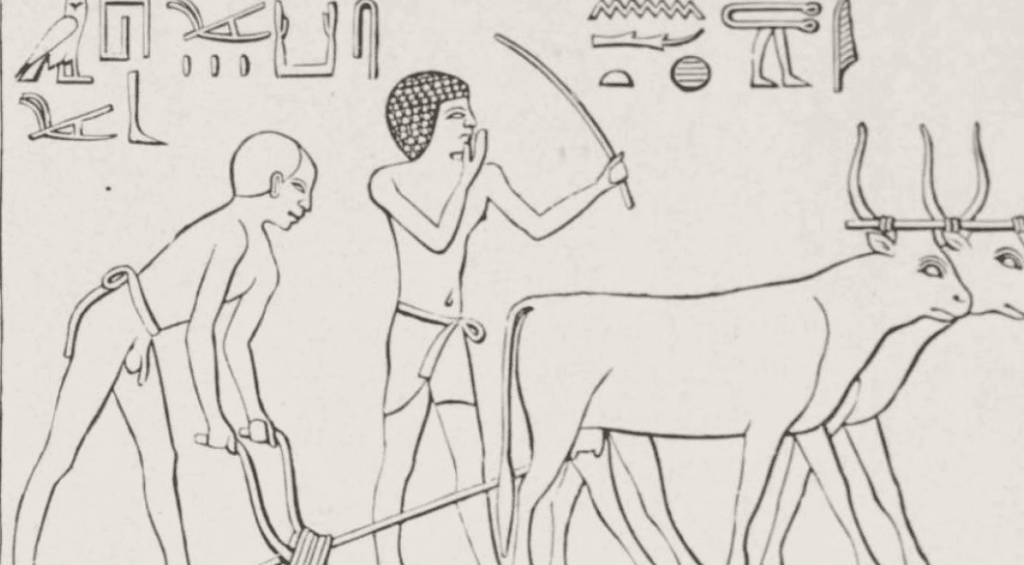

Fourth, based on joint work with the archaeologist Amy Bogaard, we reason that the subsequent development of capital-intensive, labour-saving methods of production, particularly plow-based farming, raised the value of land and other capital goods relative to labour (Bogaard et al. 2019, Fochesato et al. 2019). This increased the value of forms of wealth – land and draft animals – that, unlike the capacity to perform labour, could be very unequally held, were readily transmitted across generations, and were subject to increasing returns and substantial shocks, jointly increasing the inequality of wealth.

Fifth, the gradual centralisation of the effective use of coercion represented by the first archaic proto states, and later by conventional states, mitigated the likelihood of either internal or external challenges to the wealth holdings of the elite – including their stores, homes, animals, and eventually land – thereby providing the political conditions for enduring wealth inequalities fostered by the change in farming technology.

Sixth, with the concentration of political power, the enslavement of people converted labour itself into a form of privately owned material wealth that could be very unequally held and transmitted across generations. Enslavement of a substantial fraction of the labour force (e.g. in the Roman Empire) thus complemented changes in technology to elevate the importance of material wealth (enslaved labour itself) in production, resulting in a large class of people without material wealth whose forced labour elevated the returns to their owners’ other forms of wealth.

Wealth inequality across four configurations of technology-institutions-culture

Figure 2 provides the distribution of estimates of the degree of wealth inequality under the four configurations of technology-institutions-culture central to our account: first, labour and land-limited economies, respectively, both lacking any substantial degree of political centralization; land-limited economies with archaic proto states; and land-limited state-governed economies based on enslaved labour.

A common explanation for the rise of economic inequality, initially advanced by Friedrich Engels and Louis Henry Morgan in the late 19th century, held that the emergence of a surplus over subsistence made possible by producing food rather than hunting and gathering is the key to explaining the origin of high levels of inequality (Engels 2010 [1884], Morgan 1963 [1877]). Robert Allen provides a recent statement along these lines, interpreting “the archaeological record … in terms of changes in labour productivity … and the size of the associated agricultural surplus” (Allen 2024).

But there is little evidence that early farming actually increased productivity in terms of calories available for consumption per hour of labour (Bowles 2011). A further flaw in this reasoning was noted in passing (but not addressed) by Gordon Childe, an important archaeologist of the emergence of stratification in western Eurasia: if farming did indeed raise labour productivity, why did farmers simply not reduce their hours of work? The origin of the surplus “was initiated”, Childe wrote, when “society persuaded or compelled the farmers to produce a surplus of foodstuffs over and above their domestic requirements, and by concentrating this surplus used it to support a new urban population of specialised craftsmen, merchants, priests, officials, and clerks (Childe 1946).

Figure 2 The origins of enduring economic inequality: Distribution of estimated wealth inequality in four technology/institution configurations before 525 CE

Notes: Pink bars give the frequency distribution of Gini coefficients for the economies classified as labour limited that were not governed by states with the mean Gini coefficient for that set of observations indicated by the vertical arrow above the bars.

The anthropologist Melville Herskovits, who like Childe saw a surplus over customary consumption as a key development in explaining social stratification, pointedly remarked: “Just why the surplus is produced remains obscure” (Herskovits 1952).

A key step in this process, if we are right, was not the initial development of an agricultural surplus or the prior emergence of an extractive elite with coercive powers. Instead, it was the introduction of the ox-drawn plow. This and similar labour-saving and land-using innovations effectively increased the scarcity of land and the redundancy of labour, providing the conditions for the emergence of a subordinate class of workers. Our estimates (Figure 2) and model suggest that the increase in wealth inequality between the labour-limited and land-limited economies prior to the emergence of the archaic proto-state is the result of both an increase in the intergenerational transmission of wealth, and (non-insured) wealth shocks.

Clues about contemporary and future disparities

Turning to more recent evidence and the future, there are two striking features of the data in Figure 1.

First, the abrupt Bronze Age inequality revolution (as we have called it) increased wealth inequality to levels that have persisted (largely without trends or major modifications) to the present century.

Second, with the exception of the distinctions in Figure 2 (more unequal economies based on enslaved labour and less unequal societies not governed by states), none of the familiar institutional categories (capitalist economies, free cities, empires, other autocratic states) is systematically related to the level of wealth inequality in our data set to the present. The liberal democratic states in our larger data set (including Sweden and Finland) exhibit almost exactly the level of (pretax) wealth inequality first established by the inequality revolution in Bronze Age western Eurasia. These elevated levels of enduring wealth inequality have been sustained over five millennia by seemingly very heterogeneous sets of institutions, cultures, and technologies.

There are definitely contemporary analogies in our account of the prehistoric inequality revolution. By displacing labour, the ox-drawn plow is just a Neolithic robot (or AI algorithm); estimates of their labour-displacing effects are remarkably similar (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020, Halstead 1995). But whether these contemporary technologies enhance the value of privately held material wealth, thereby increasing economic inequality, will depend on the nature of the property rights establishing control over and claims on the income streams associated with these techniques. This is more a matter of politics and institutions than of technology. The crucial role of the concentration of political power in our account of the origins of enduring inequality suggests that recent increases in wealth disparities could prove ephemeral in liberal democracies, barring institutional changes that allow greater concentration of power by economic elites.

Source : VOXeu