There are growing concerns that low-income countries may be in or close to a systemic debt crisis. This column argues that while debt distress indicators in these countries have been steadily rising over the last decade, they remain substantially below their levels in the mid-1990s and do not yet indicate a systemic crisis of the type that would require a wholesale, coordinated Heavily Indebted Poor Countries-style initiative. However, the window to prevent the next big crisis may close fast, if we don’t act now.

There are growing concerns that low-income countries (LICs) may be in or close to a systemic debt crisis, resembling the situation in the mid-1990s that led to the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) debt relief initiative. Some argue that the situation already requires another HIPC-style and Brady-type solution and that the absence of a well-coordinated, globally accepted, and predictable path towards debt restructuring could result in the breakout of a cascading debt crisis that could reverse hard-won development progress over the decades (Debt Justice 2023, Malpass 2023, Coulibaly and Abedin 2023, Rogoff et al. 2021). In this column, we show that while debt distress indicators in LICs today have been steadily rising over the last decade, they remain substantially below their levels in the mid-1990s. Hence, LICs are not yet in a systemic crisis of the type that would require a wholesale, coordinated HIPC-style initiative. This is good news, because changes in the creditor and geopolitical landscape would make such initiative much harder to carry out than 25 years ago. The bad news is that the window to prevent the next big crisis may close fast, if we don’t act now.

We are not there yet

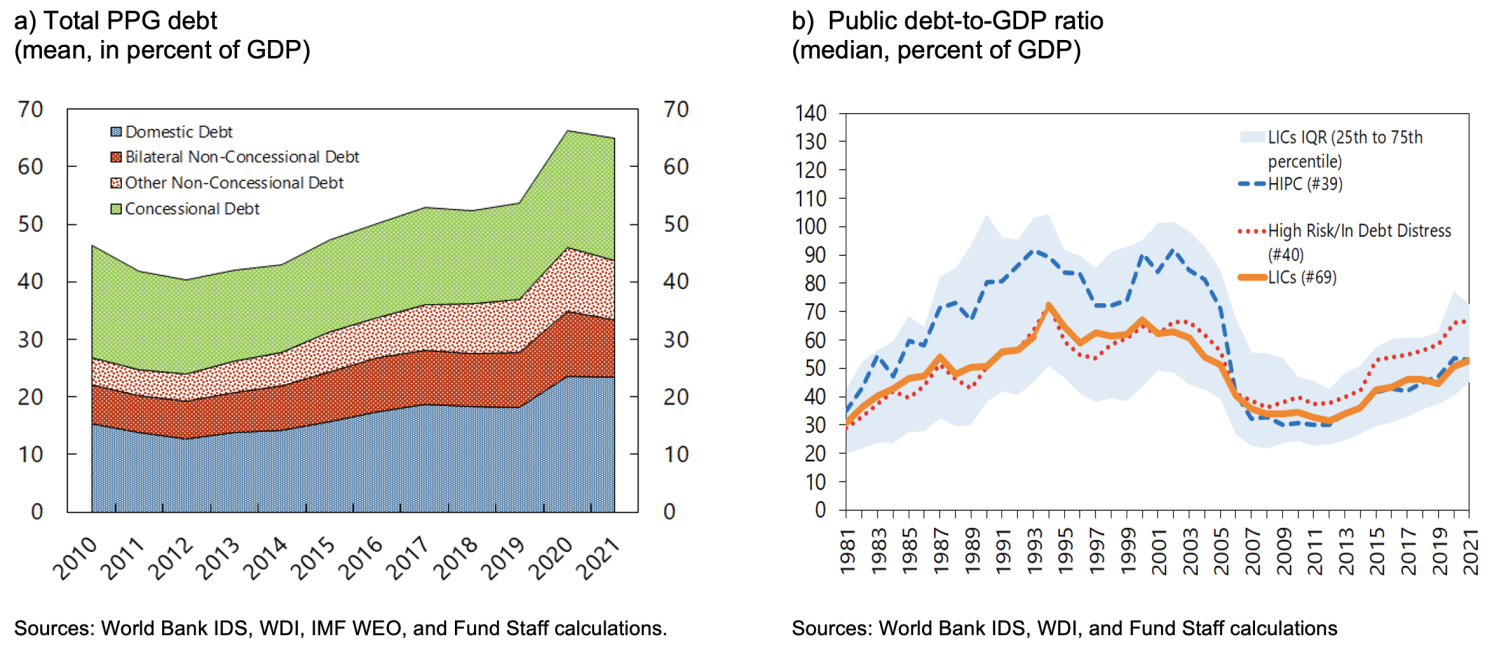

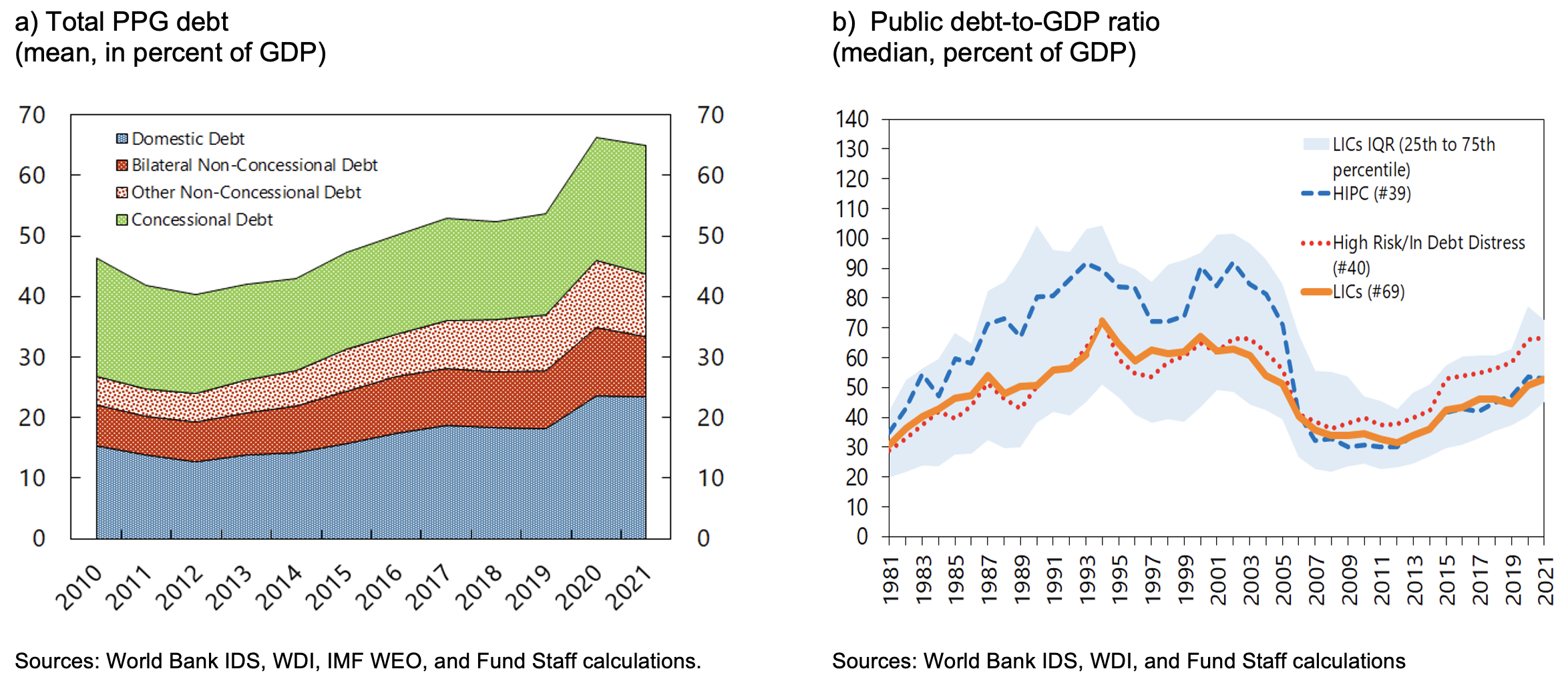

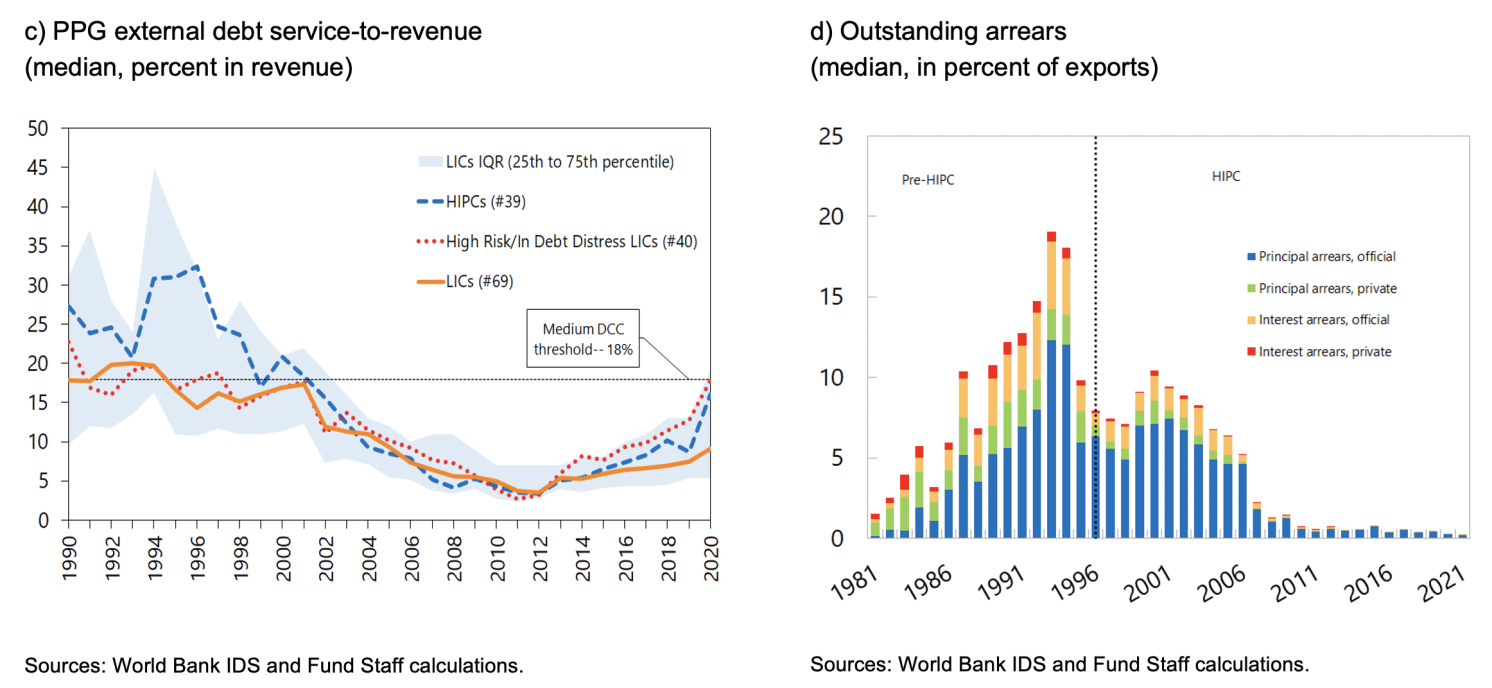

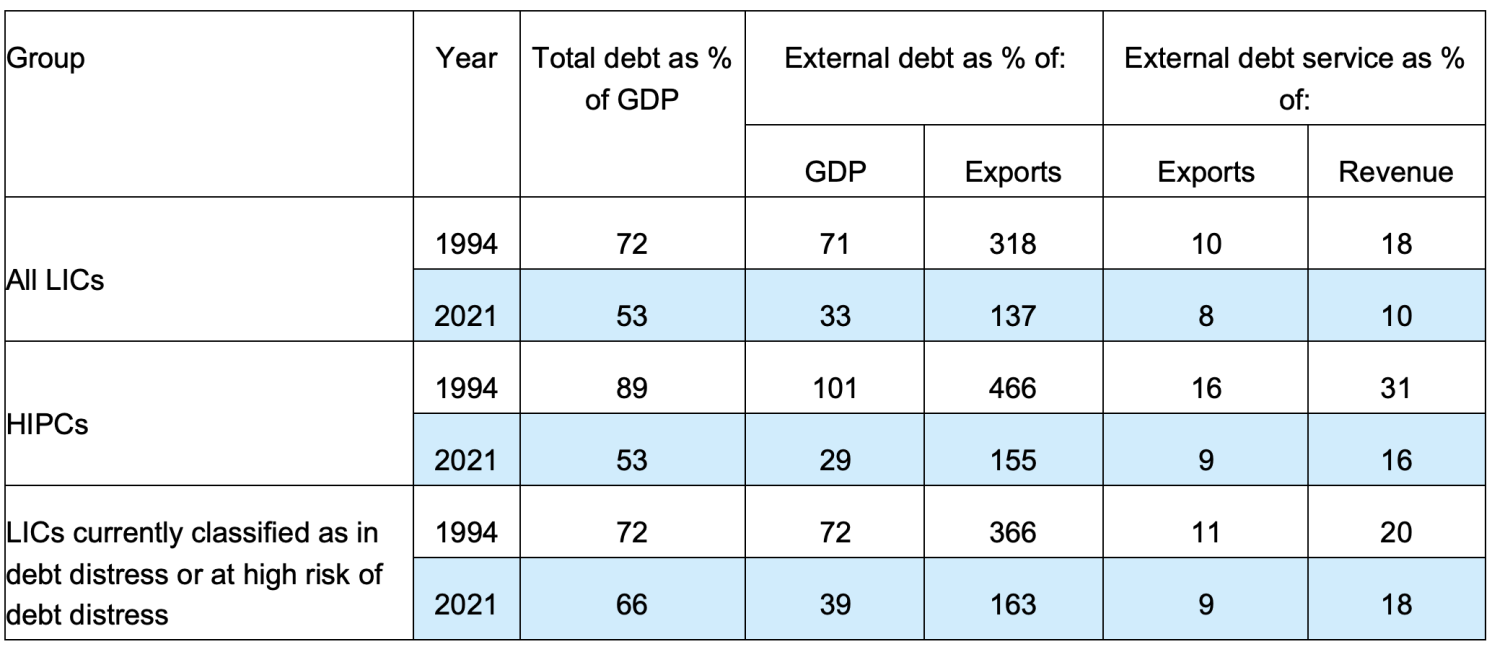

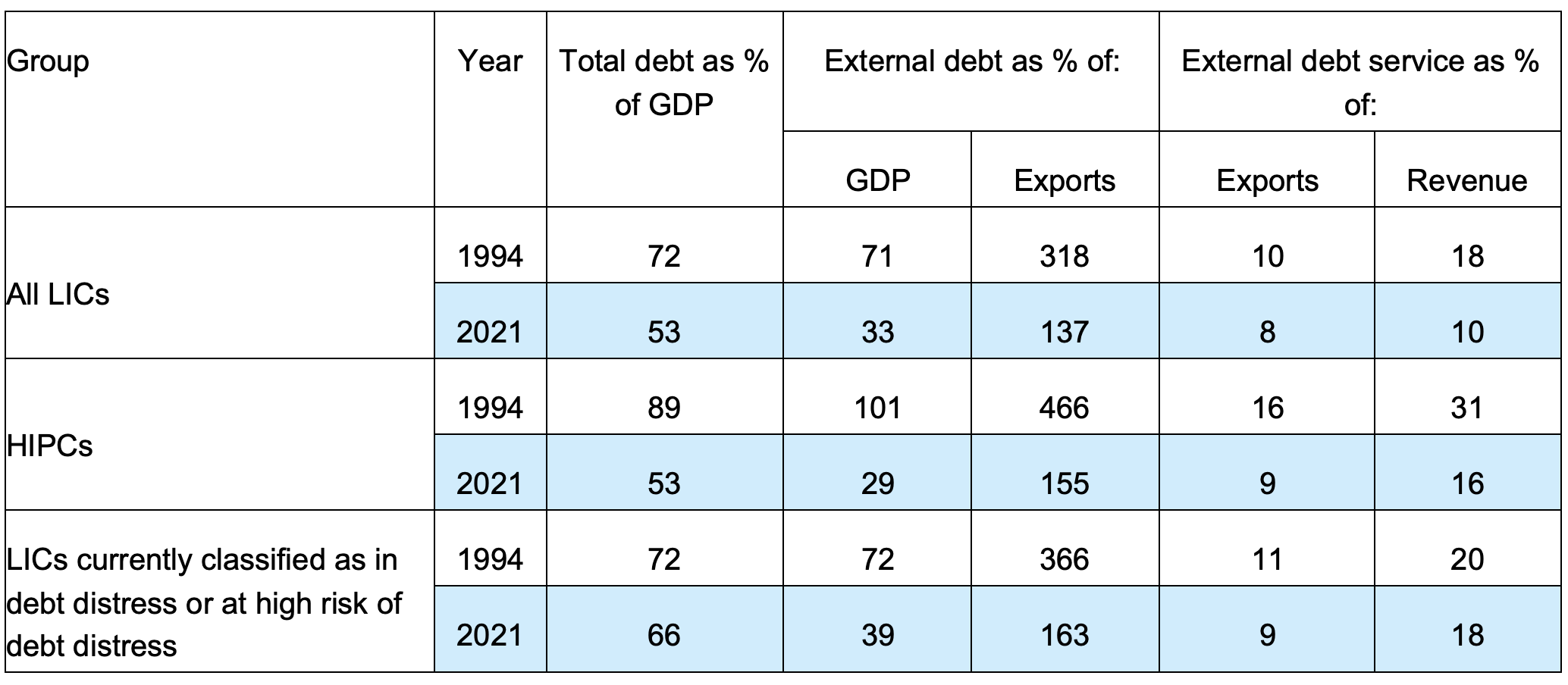

In a recent paper (Chuku et al. 2023), we compare todays’ debt vulnerabilities in LICs with the situation in the mid-1990s. Total public and publicly guaranteed debt-to-GDP ratio in LICs increased by an average of one percentage point per annum during 2010-19 and jumped by 13 percentage points in 2020, driven mainly by domestic and external non-concessional debt (Figure 1a). However, debt vulnerabilities in LICs remain substantially less alarming on average than they were in the mid-1990s. The median public debt-to-GDP ratio of a typical LIC was 72% at end-1994, well above the highest tolerable threshold of 55% for LICs with strong debt-carrying capacity in today’s LIC-DSF framework. In contrast, the median debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 53% at end-2021 (Figure 1b). Narrowing the focus of the comparison to the subset of 39 heavily indebted poor countries in the 1990s versus the 40 LICs currently in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress today, the debt-to-GDP ratio is about 23 percentage points lower today (Table 1).

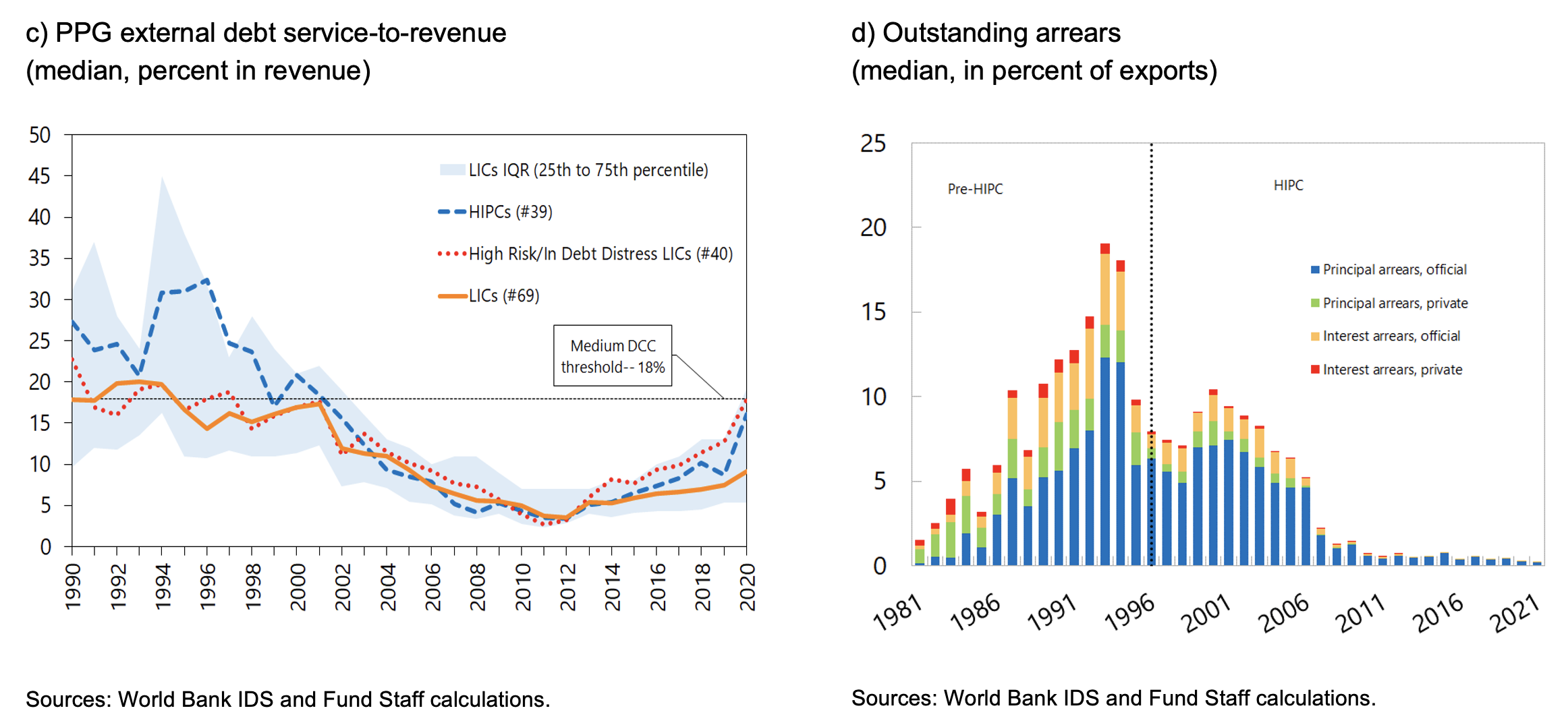

Similarly, a comparison of the liquidity indicators in LICs also suggests lower debt risks today compared to the debt crisis of the mid-1990s. The median LIC had to use about 18% of its revenues to service external debt in 1994. Today the median LIC spends about 10% of revenues on external debt service, below the most restrictive threshold of 14% for countries with a weak debt-carrying capacity. (Figure 1c and Table 1). These conclusions continue to hold within and across specific subgroups of LICs for all five debt burden indicators used in the LIC-DSF framework (Table 1). Moreover, external arrears accumulation, which was widespread among LICs in the 1990s, remains subdued following the HIPC/MDRI treatment (Figure 1d).

That said, debt vulnerabilities in LICs could reach levels comparable to the pre-HIPC era over the medium- to long-term if current underlying trends persist, and especially in the absence of domestic policies and reforms to address such vulnerabilities. To illustrate, if external debt service-to-revenue ratios continue to increase at the average rate of one percentage point per annum, as observed over the past decade for the median LIC (or 2 percentage points for LICs in distress or at high risk of distress), liquidity pressures could reach similar levels as the pre-HIPC era within 7 to 10 years for the median LIC (or less for those in distress or at high risk of distress).

Figure 1 Debt burden indicators in LICs

These conclusions are subject to important caveats. Domestic debt in LICs has been rising as a share of total debt and the implications are not fully captured in the external debt indicators of the LIC-DSF used for the analysis. In countries without financial repression, domestic debt is generally more expensive and of shorter maturity than foreign debt; hence, an increasing share of domestic debt might lead to a higher debt burden even if total public debt is unchanged (or even declining). Also, liquidity risks associated with domestic debt service are not included in the analysis for lack of systematic cross-country data. As a result, these indicators both understate total liquidity risk and – given the rising share of domestic debt – overstate the extent to which liquidity risk has come down compared to the mid-1990s. However, given the size of the margins of the debt service indicators in 2021 and 1994 (Table 1), the inclusion of domestic debt service would be unlikely, in principle, to change the conclusion that median debt service burdens are comparatively lower today, though it could well change such assessment for individual countries.

Table 1 Debt burden indicators: Pre-HIPC versus today

Sources: World Bank IDS, IMF WEO, and Fund Staff calculations.

Note: The table compares the main solvency and liquidity indicators that enter the IMF-World Bank debt sustainability framework for low-income countries (LIC-DSF) for three groups of LICs: LICs that are today classified as in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress; HIPC countries; and all LICs. The fact that these indicators looked much worse in 1994 than in 2021 for the HIPC group is not surprising – as the HIPC was selected based on similar indicators in the mid-1990s. However, the indicators still look better today when focusing on the average for all LICs, or even for the LICs that are currently classified as in debt distress. For the last group, stress indicators today (row 6) look less bad compared both to the same countries in 1994 (row 5) and to the HIPCs in 1994 (row 3).

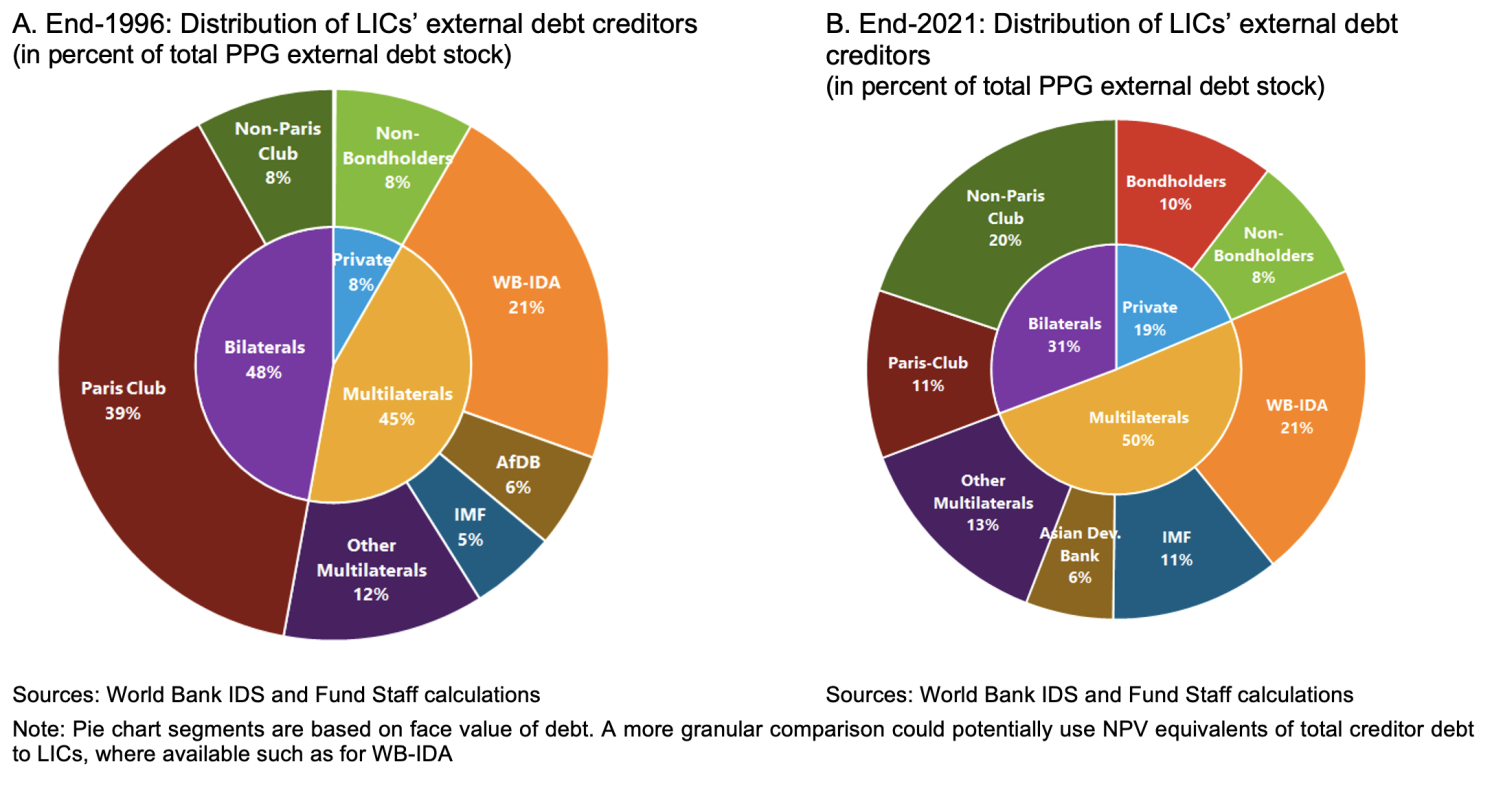

Navigating the more complex creditor and geopolitical landscape

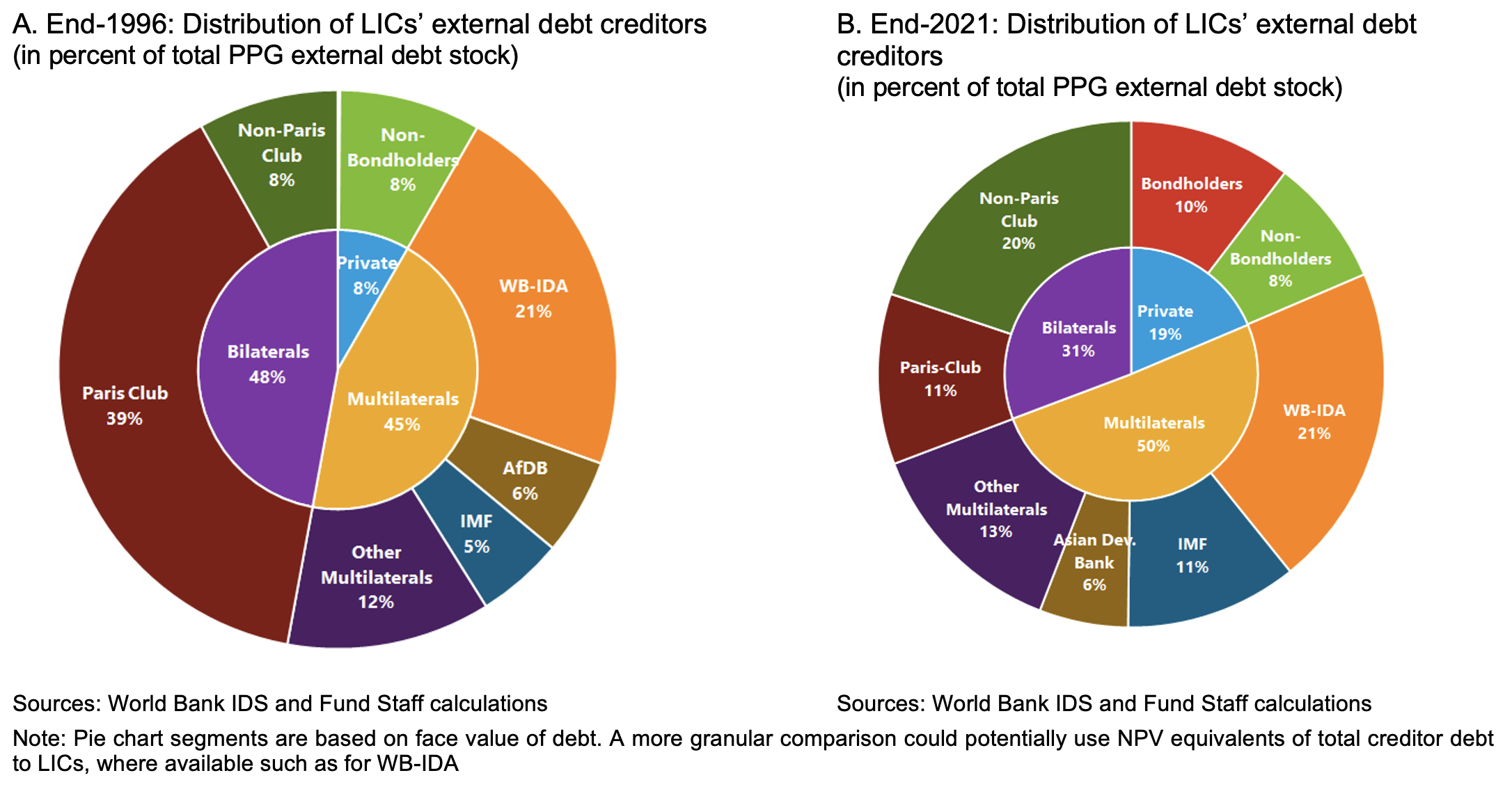

LICs now face a more diverse creditor landscape than during the pre-HIPC era, most notably new official bilateral and private creditors, new types of instruments, and greater reliance on domestic debt. The share of non-Paris Club credit to LICs has almost tripled from 8% to 20%, private sector debt has approximately doubled from 8% to 19%, and domestic debt as a percent of GDP has tripled from 8% to 24% (Figure 2). Moreover, there is a significant concentration of holdings by a few major external creditors. In the 1990s, the top-five external creditors to LICs accounted for 60% of total external credit to LICs and consisted of multilateral and Paris Club creditors. As of end-2021, the concentration of the top-5 external creditors had further increased, accounting for 75% of total external credit to LICs, with China being by far the largest official bilateral creditor (Chabert et al. 2022, Reinhart et al. 2022).

Given the significantly transformed financing landscape today, as well as much higher geopolitical tensions, efforts at establishing a second-generation of HIPC-type solution would face challenges that did not exist in the mid-1990s. This explains both the creation of new coordination mechanisms – such as the G20 Common Framework – and the difficulties in getting the new mechanisms to work (Georgieva and Pazarbasioglu 2021). Moreover, donor fatigue from official bilateral creditors would likely dampen appetite for another HIPC-style framework with a correspondingly broad perimeter of claims for inclusion recently advocated by some (Kebret and Ryder 2023).

Competing demands for concessional resources to meet the huge development needs in LICs, including for climate adaptation (Zettelmeyer et al. 2022), makes the traditional HIPC approach to debt relief and the calls for IFI participation more challenging, and possibly self-defeating today. Funding debt relief by IFIs would imply crowding-out bilateral donor resources and earned investment income from IFIs that could otherwise be used to finance the scale-up of IFI concessional lending to LICs. Moreover, IFI participation in debt relief would only contribute marginally to solving debt challenges in LICs since the NPV of IFI debt is much lower compared to other sources of debt (Chuku et al., 2023). Fresh injections to IFIs should rather be channeled toward increasing their capital base and/or funding their subsidy accounts to scale concessional financing to LICs.

Figure 2 Rebalancing in LICs’ financing landscape

Preventing a systemic debt crisis in LICs

Going forward, reducing debt burdens before debt vulnerabilities become systemic should be a key priority. Economic recovery policies and external financial support should focus on generating vigorous, sustainable and inclusive growth, improving debt sustainability in the process. Countries currently in debt distress or whose debt becomes unsustainable should not delay a restructuring where needed, including through the G20 Common Framework. On the part of the international community, efforts should be geared toward strengthening the G20 Common Framework and scaling up concessional finance to help countries meet development and climate goals. The Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR), launched in February, brings together official bilateral creditors (Paris Club and non-Paris Club), private creditors, and debtor countries to build greater consensus on debt and debt restructuring processes, which can help accelerate and foster global collective action.

Whether a broader debt restructuring initiative beyond the currently available mechanisms would be required for LICs would depend on the success of these efforts. The evidence suggests that it is still possible to avert another debt crisis in LICs – provided action is taken now.