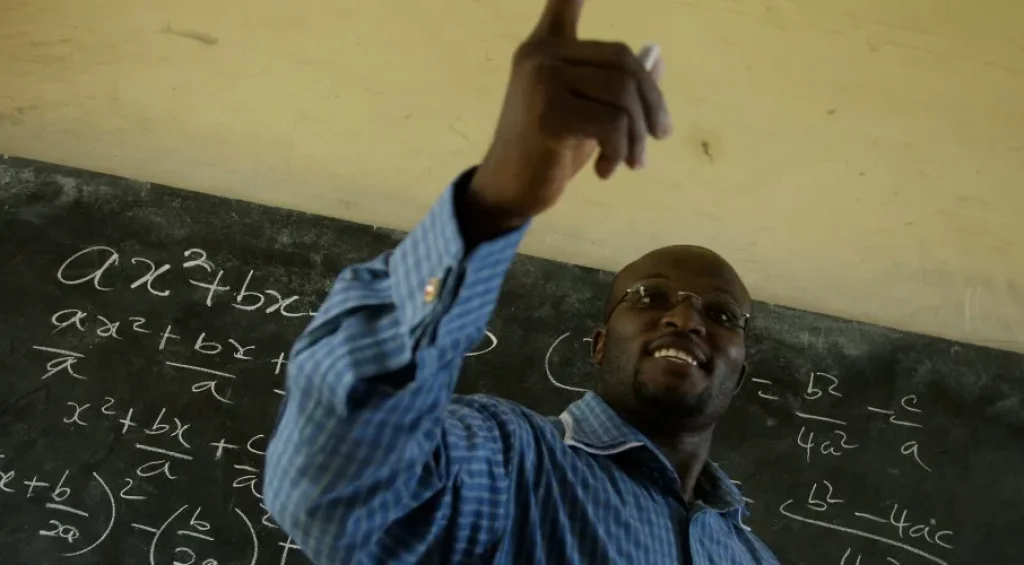

A sandy corner of South-Eastern Morocco hosts what could be the key to achieving the world’s net zero ambitions. It is a research center for renewable energy storage built by Masen, the Moroccan Sustainable Energy Agency, that conducts research and testing on new ways to create and store solar energy. The World Bank’s ESMAP has joined several innovative private sector firms to support this research center that is specifically designed to serve the energy storage needs of the developing world.

Why is this so important? Energy storage is key to secure constant renewable energy supply to power systems – even when the sun does not shine, and the wind does not blow. Energy storage provides a solution to achieve flexibility, enhance grid reliability and power quality, and accommodate the scale-up of renewable energy. But most of the energy storage systems developed to date are not suited for the distinct conditions and use cases of the developing world.

Energy storage systems do not follow a one size fits all approach. And the needs of developing countries have often been overlooked. Developing countries frequently feature weak grids. These are characterized by poor security of supply, driven by a combination of insufficient, unreliable and inflexible generation capacity, underdeveloped or non-existent grid infrastructure, a lack of adequate monitoring and control equipment, and a lack of maintenance. In this context, energy storage can help enhance reliability. Deployed together with variable renewable energy like wind and solar, it can help displace costly and polluting fossil fuel-generated electricity, while increasing security of supply. Storage can also help defer or avoid the construction of new grid infrastructure.

That is why the Masen testing site, also called testbed, is located in a harsh desert environment. Not only can it replicate the climate conditions in which the storage systems will be housed, but it can also provide testing conditions for their ultimate use cases, such as providing night-time low voltage power for critical needs like local hospitals.

The testbeds are being built with these conditions, needs, and use cases in mind. The idea is that with the right storage systems in place, the real potential of renewable energy can be met, and with that, the world can start to meet its net zero obligations.

Scaling Storage Systems

It is increasingly clear that the global deployment of renewable energy is dependent on scaling up storage systems. It is the frontier that must be crossed to reach net zero and universal access to clean energy by 2030. For instance, Morocco itself has a target of having 52% of its installed capacity coming from renewable sources, but this is not a target it can reach without energy storage to provide the essential flexibility needed for renewable energy production at scale.

Solar PV is already the cheapest source of electricity but without storage it cannot be properly harnessed. The only way to put more of that PV into grids or into national plans for capacity expansion is if there is storage to match demand and production of electricity.

The evolution of renewable energy has come in two distinct phases. From 2010 to 2020 the overall pricing of renewable energy systems – especially for solar and wind energy – either dropped below or reached parity with fossil fuels in most countries. This incentivized a huge increase in new projects. But since then, what has become apparent is that solar and wind projects have placed huge pressures on national grid systems, which typically can only absorb around 30% of the new solar and wind power that is generated.

In addition to new storage technologies, energy storage systems need an enabling environment that facilitates their financing and implementation, which requires broad support from many stakeholders. ESMAP has created and hosts the Energy Storage Partnership (ESP), which aims to The goal is to finance 17.5-gigawatt hours (GWh) of battery storage by 2025 – more than triple the 4.5 GWh currently installed in all developing countries. So far, the program has mobilized $725 million in concessional funding and will provide 4.7 GWh of battery storage (active projects), supplemented by 2.4 GWh (future pipeline).

The ESP is currently working to develop a solar PV plus battery storage hybrid power purchase agreement (PPA) framework. PPAs are the backbone of all power projects as they help determine, for example, who will buy the electricity and at what price. This brings the certainty necessary to get projects financed.

Creating this PPA framework as a global good will allow for the systematic deployment of storage systems around the world, moving beyond the project-by-project approach. It will also allow far greater volumes of finance to enter the sector, especially from the private sector.

Mainstreaming energy storage systems in the developing world will be a game changer. They will accelerate much wider access to electricity, while also enabling much greater use of renewable energy, so helping the world to meet its net zero, decarbonization targets.

The Energy Storage Partnership held its Stakeholder Forum and the 9th ESP Partner Meetings June 26-30, 2023, with more than 40 countries represented. Our thanks go to our hosts, the United Kingdom Government – through the UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) – and Loughborough University. This is the first time the ESP Stakeholder Forum was held in the UK.

Source : World Bank