Uncertainty can affect firm decisions because it leads to more cautious behaviour and is associated with learning about viability of the business. Based on a novel survey of German firms, this column finds that uncertainty reflects change. Firms’ planning incorporates higher subjective uncertainty about their future sales growth when they have just experienced unusual – especially negative – growth. In addition, firms’ subjective uncertainty tracks the conditional volatility of shocks at the quarterly frequency: both exhibit an asymmetric V-shape in past growth. In contrast, medium-term subjective uncertainty differs from conditional volatility: Successful firms – large or fast-growing – have lower subjective uncertainty than unsuccessful firms even with same-sized shocks.

Firms’ planning under uncertainty is a key building block of macroeconomic models. Two channels through which uncertainty affects firm actions have received particular attention in the literature. On the one hand, in many business cycle models, firms’ cautious behaviour in recessions contributes to lower investment and hiring (Bloom 2009, Morikawa 2016, Bloom et al. 2018, Den Haan et al. 2021, Coibion et al. 2022; see also Bloom 2014, Fernandez-Villaverde and Guerron-Quintana 2020, and Cascaldi-Garcia et al. 2023 for surveys of the literature on business cycle models with time-varying uncertainty). On the other hand, studies of firm heterogeneity often assume that new firms learn about the viability of their business model over time (see Hopenhayn 2014 for an overview of models of firm dynamics, including those emphasising learning, following Jovanovic 1982).

A common denominator of both channels is that change in a firm’s environment affects decision makers’ subjective uncertainty and not simply their forecasts (that is, their conditional expectation). While connections between uncertainty and change are prominent in theory, there is little direct evidence. In particular, we lack panel data on quantitative measures of managers’ beliefs – data that are crucial to study how firm planning deals with change and how change shapes perceptions of uncertainty (see Bachmann and Carstensen 2022 for an overview of existing data on managers’ beliefs).

In a recent paper (Bachmann et al. 2024), we characterise empirically planning under uncertainty in firms, drawing on a new panel data set of German manufacturing firms. Our survey module asks top managers not only for a forecast of one-quarter-ahead sales growth, but also for best- and worst-case sales growth scenarios. The idea behind this survey design is that managers can directly report scenarios developed as part of their firms’ regular planning process. Survey responses confirm that most firms engage in scenario analysis and use results from routine quantitative planning to fill out the questionnaire. To summarise how a firm’s perceived uncertainty is reflected in its planning, we focus on the span between its scenarios, that is, the difference between best- and worst-case sales growth rates. Our focus is to analyse how this quantitative measure of subjective uncertainty varies over time and across firms.

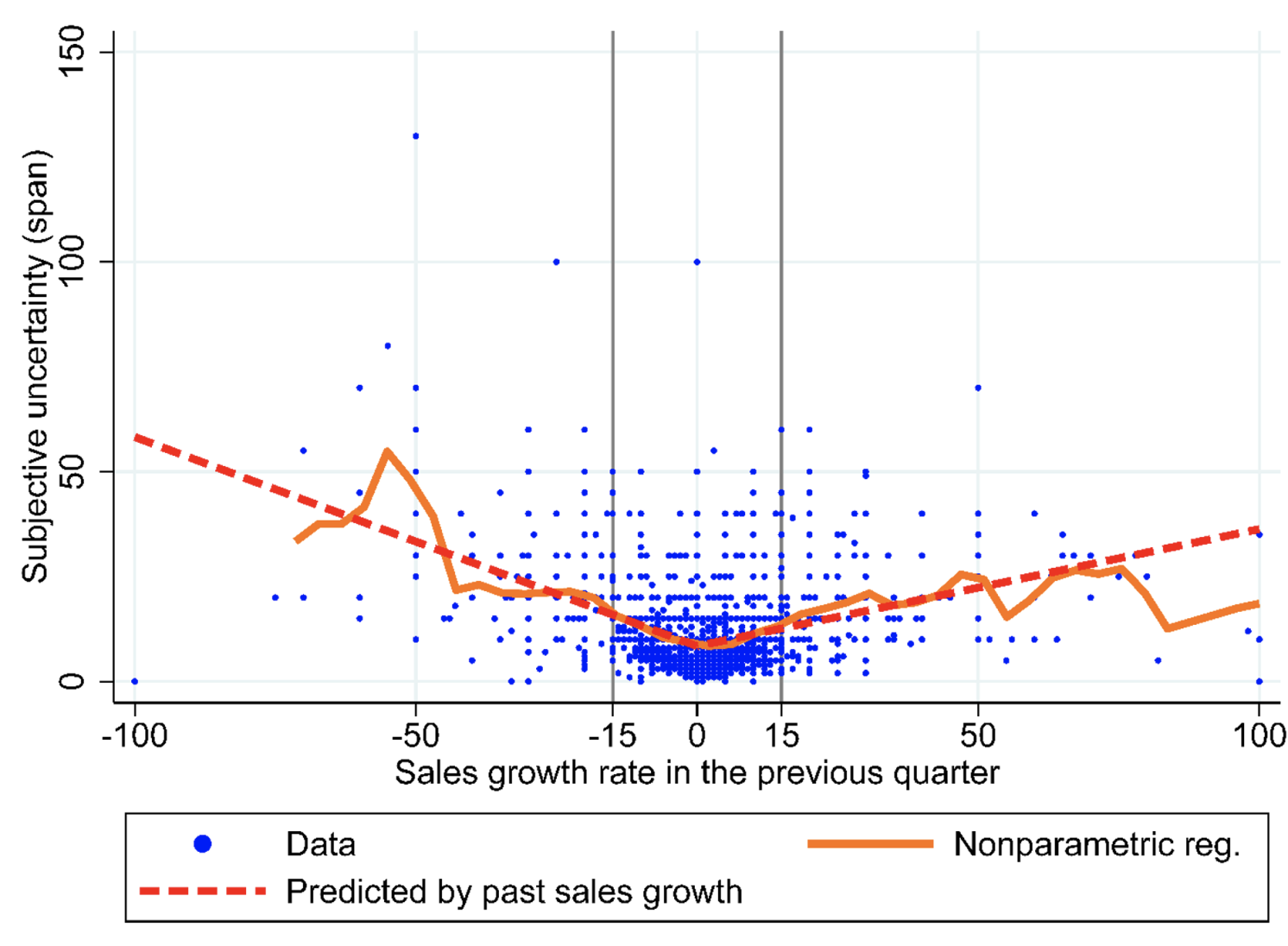

Our main result is that planning under uncertainty responds strongly to change in the environment of a firm. It provides support for both channels emphasised in the literature but suggests that both are special cases of a more general principle: a firm’s planning reflects higher subjective uncertainty when the firm experiences unusual growth, and more so if the experience is negative. At the quarterly frequency for a given firm, Figure 1 shows that the relationship between span and lagged growth is well described by an asymmetric V-shape with a minimum at zero, a steep negative branch and a flatter but significant positive branch. While a one percentage point lower negative growth rate is followed by a 31 basis point wider span between firms’ best and worst case scenarios, a one percentage point higher positive growth rate widens the span by only 18 basis points. These findings are robust to including controls for firm heterogeneity. We find this pattern in a sample without a recession, where most time-series variation is idiosyncratic. In the cross-section of mature firms, the span is wider not only for fast-growing firms, but also, and even more strongly, for fast-shrinking firms – again, an asymmetric V-shape. We conclude that higher uncertainty matters for a firm’s planning not only in recessions or at young age, but whenever firms enter unfamiliar territory through experienced change.

Figure 1 Uncertainty and past sales growth

Notes: Every dot represents a firm-quarter observation. The solid orange line is the prediction from a kernel-weighted local polynomial regression of degree zero with an Epanechnikov kernel where the bandwidth was selected based on the rule of thumb suggested by Fan and Gijbels (1996). The dashed red line depicts the predicted values from a piecewise linear regression of subjective uncertainty on past sales growth, with a break at zero. The thin vertical lines mark the inter-decile range that extends from 15% to 15%.

How does subjective uncertainty relate to the conditional volatility of shocks experienced by the firm? This relationship depends on the frequency at which change occurs. Quarterly variation in subjective uncertainty is quite similar to that in the conditional volatility of forecast errors, estimated by fitting a power generalised autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) model: both measures of (conditional) uncertainty exhibit mild persistence and an asymmetric-V-shaped response to lagged growth. In the short run, managers’ planning under uncertainty thus reflects their anticipation of the size of future shocks. In this sense, managers appear to understand experienced change.

Over the medium term, by contrast, experienced change goes along with systematic bias in both forecasts and perceptions of uncertainty. Indeed, for firms on either good or bad growth trends, managers’ forecasts are consistently too close to the status quo. Moreover, managers’ subjective uncertainty cannot be proxied by the conditional volatility of forecast errors: planning in growing firms reflects lower uncertainty than in shrinking firms even when the firms are faced with shocks of the same size. We find the same result for large compared to small firms. Success thus breeds confidence that disconnects planning under uncertainty from conditional volatility.

Our data come from a new module of the ifo Business Survey, a long-established survey administered by the Munich-based ifo institute used to develop business sentiment indicators in Germany. The survey is well-regarded in the German business community: questions are typically answered by senior management and there is a high response rate even from large firms. Our analysis uses a quarterly sample over four years from 2013 to 2016, which allows us to explore both time-series and cross-sectional variation in planning behaviour. Bachmann et al. (2023) provide an introduction to the data set and further discussion of data quality.

To provide an idea of magnitudes, the mean span between best- and worst-case quarterly sales growth scenarios is 12.1 percentage points, slightly above the mean absolute forecast error. Firms differ in their average subjective uncertainty: the cross-firm standard deviation of time-averaged span is 7.4 percentage points. At the same time, we document large time variation in subjective uncertainty for individual firms: the time-series standard deviation of span for the average firm is 5.9 percentage points. The time-varying span is thus a volatile component of firms’ planning processes. In fact, it is almost as volatile as the usual driver of firm planning in economic models, namely, changes in conditional expectations: the average firm’s time-series standard deviation of growth forecasts is 7.4 percentage points. Most of the time-series variation in subjective uncertainty is firm-specific; time-industry fixed effects explain only a negligible share.

Our results provide direct evidence for time variation in subjective uncertainty, as is required for mechanisms from the business cycle literature to operate. At the same time, we emphasise large idiosyncratic variation. Mechanisms used to explain recessions should therefore be relevant also for firm dynamics in normal times. They shape the cross-sectional distribution of firms, the key state variable determining the reaction to aggregate shocks in heterogenous-firm models. However, models have to be consistent with a V-shaped relationship between uncertainty and past growth, which rules out uncertainty shocks that affect current growth, but are orthogonal to past growth. Our results further suggest that a model of firms’ planning at the quarterly frequency should draw a connection between subjective uncertainty and conditional volatility, such as that traditionally provided by the rational expectations assumption. Firms adjust their planning process based on the experience that high and, even more so, low growth signals larger future surprises.

There are several candidate reasons for why uncertainty responds to change quarter-to-quarter. One possibility is a learning process such that uncertainty increases with forecast errors. We indeed document a positive relationship between lagged absolute forecast errors and span. This result is related to Boutros et al. (2020), who find that executives who provide confidence intervals for stock returns widen those intervals when the realised return falls out of their last interval. However, our managerial forecasts of sales growth also reflect a second force: uncertainty increases with predictable bad change. Indeed, for firm quarters with negative growth, the previous-quarter growth rate is sufficient for predicting span. This is because predictable low growth realisations increase uncertainty in the same way as growth surprises. A possible explanation is that planning takes into account state variables in addition to growth. For example, in a model with customer capital, a shrinking firm might see the size and/or composition of its future pool of customers and thus its sales growth become more uncertain even when this shrinking occurs in a predictable way.

Source : VOXeu