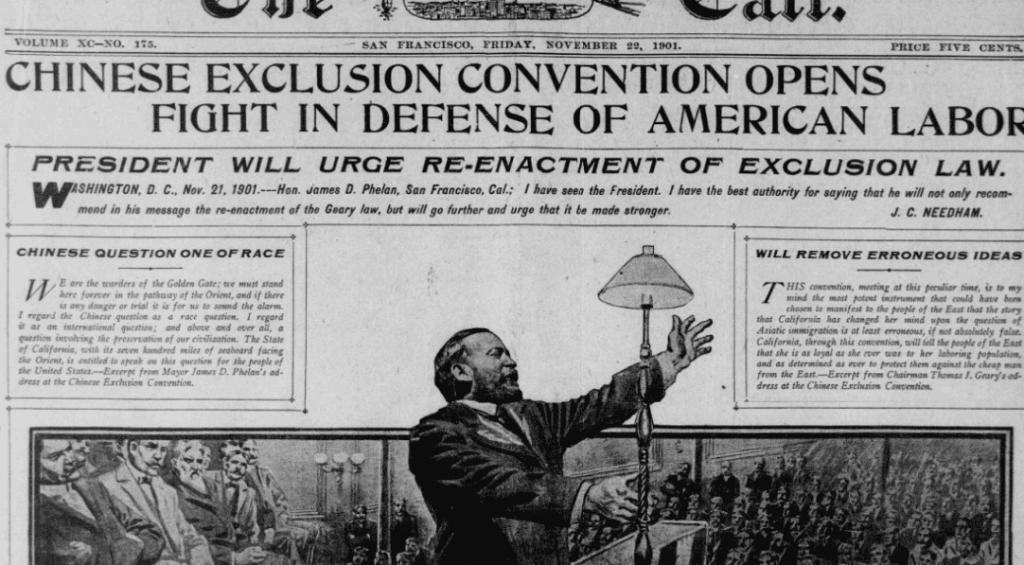

Immigration is one of today’s most controversial policy issues. A recurrent concern is that immigrants are taking the jobs of native workers, leading many governments to consider restrictions and even deportations. This column examines the impact of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which effectively shut down Chinese immigration to the US for more than 80 years, on economic growth and labour markets. The authors find that the Act reduced the labour supply and the earnings growth of native-born workers, and slowed down manufacturing output and economic growth in the US West, with effects that persisted until at least 1940.

International migration is at a historical peak. As of 2022, there were more than 280 million international immigrants around the world (IOM 2024) – up by almost 30% relative to just a decade before. In 2023, the immigrant population share in the US was 14.3% (Moslimani and Passel 2024), more than three times larger than the same figure for 1970, and close the historical peak of 14.8% in 1890. The analogous numbers are 23% for Germany, 20% for Spain, 15% for France, and 13% for Italy. 1 Civil and international conflict, as well as natural disasters, are projected to increase the global immigrant population above one billion individuals by 2050 (McAllister 2024).

Immigration is one of today’s most controversial policy issues. Governments that receive large numbers of immigrants are struggling with logistical, political, and economic challenges, and anti-immigrant sentiments are on the rise in many countries around the world. A recurrent concern is that immigrants are taking the jobs of native workers (e.g. Le Monde 2024). To address these challenges, many governments are considering restrictions (e.g. BBC News 2024) and even deportations (e.g. New York Times 2024). The logic behind these policies is that immigrants compete with native workers for jobs and reduce employment and wages for the latter. Reducing the number of immigrants should thus improve the economic outcomes of native workers (Borjas 2003), especially when macro-economic growth is slow and there are more workers than jobs. Yet, many economists argue that immigrants, for the most part, improve economic growth (Nunn et al. 2017) and can often benefit native workers (Ottaviano and Peri 2008). This can be because they have skills that complement those of native workers or because there are economies of scale in production and innovation. Under this logic, a large reduction in the number of immigrants can be harmful to the local economy and native workers.

Ultimately, the effect of a large reduction of immigrants is an empirical question. In our recent paper (Long et al. 2024), we address this question by focusing on the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This was America’s first ban on voluntary immigrants based on their country of origin or ethnicity. It prevented labourers born in China from entering the US and those already residing in the US from obtaining citizenship or re-entering the country if they left temporarily (for example, to visit families at home). The Act was widely popular, and its proponents argued that Chinese workers, who constituted 12% of the male working-age population and 21% of all immigrants in the Western US, reduced economic opportunities for white workers. The Chinese Exclusion Act was opposed by business owners, who worried that Chinese labour could not be easily replaced and that a wide-sweeping ban would lead to significant economic losses.

We consider the eight western states where almost all Chinese immigrants resided at the time – Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming – for the 1850-1940 period. We compare the evolution of economic outcomes in US counties that were more and less impacted by the Chinese Exclusion Act, before and after the Act. We leverage two sources of variation: first, time variation from the introduction of the Act (i.e. before versus after 1882); and second, geographic variation in the intensity of the Act, which was stronger in areas where more Chinese were already living in 1880. This strategy allows us to account for any county time-invariant characteristic that might have simultaneously influenced the trajectory of economic growth and determined the location decision of Chinese immigrants. We also account for state-specific changes over time, such as differential population and economic growth rates. Since the location of Chinese workers in 1880 was not random (the first waves of Chinese immigrants worked in mining and railway construction, and subsequent immigrants often moved to locations where earlier immigrants concentrated), our strategy allows counties to be on differential trends depending on the number of years of connection to a railroad and on whether there was any active mine between 1840 and 1882.

Main results

In a first step, we examine the effects of the Act on labour supply. As shown in Figure 1 (Panel a), and as intended by the proponents of the legislation, the Act reduced the Chinese labour supply. However, and perhaps in contrast with politicians’ expectations, counties that were more exposed to the Chinese Exclusion Act also experienced a reduction in labour supply growth among white workers. Our results also indicate that the Chinese Exclusion Act slowed down income growth of both remaining Chinese immigrants and white workers (Panel b). Next, we investigate the impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act on output (Panel c), focusing on the manufacturing industry. This was a key and fast-growing sector for the economy of the US West during this period (on average, between 1880 and 1940, manufacturing output grew from $36,700,000 to $716,000,000, measured in 2020 dollars) and one where Chinese workers were highly concentrated (almost 20% of the Chinese labour force worked in manufacturing). We find that the Act reduced total manufacturing output and the number of establishments. We also find some evidence that the Chinese Exclusion Act slowed down labour productivity, even though these estimates are imprecise.

Figure 1

There are two main concerns when interpreting the results. The first one is that, even in the absence of the Chinese Exclusion Act, counties with a larger Chinese population share would have experienced an economic decline. To address this, we use the eastern U.S. as a ‘placebo’ sample and compare labour force and economic outcomes in counties that, based on their 1880 characteristics, would have had many Chinese immigrants to those that would have had few in the hypothetical scenario that Chinese arrived from the Atlantic. Reassuringly, we find that in the placebo states, counties with high hypothetical Chinese shares grew more – and not less – than those with low hypothetical Chinese shares after 1880. The second concern is that the Chinese Exclusion Act might have caused labour and economic activities to move from high 1880 Chinese share counties in the US West to other counties within the West, with a low 1880 Chinese share. We show that there are no spillovers to nearby areas. Under the assumption that moving costs increase with distance, this implies that reallocation does not drive our results.

Mechanisms

What explains the large negative effects of the Chinese Exclusion Act on the economic growth of the US West? First, due to travel costs and information frictions, it was hard for employers to replace the ‘missing’ Chinese workers. Indeed, our results are larger in Western counties that were more remote and were less connected to the rest of the country. Moreover, the negative effects on labour supply are driven by white men born outside of the Western states (either in other parts of the US or in Europe), while the Act did not affect men who were born in the West. In fact, the only group of white men for whom we find positive effects from the Chinese Exclusion Act are ‘local’ (i.e. born in the same state) white miners. These results also suggest that the Act discouraged prospective white migrants from moving to the West, causing them to remain in the eastern parts of the US. This supports the interpretation that the Chinese Exclusion Act reduced the aggregate economic development of the West. Second, we find that places that lost more skilled Chinese workers also experienced a larger decline in skilled white workers and manufacturing output. This result is consistent with the presence of complementarities between skilled Chinese and skilled white workers.

Taking stock

The evidence from our study highlights the complexity of economic growth. In a simplistic zero-sum framework, immigration increases competition with native workers and reduces wages and economic opportunities. This is the framework underlying many anti-immigration policies, both historically and today. However, the empirical evidence suggests that the zero-sum framework is not the correct one for considering aggregate economic effects, at least not in the medium and long run. Immigrants may complement native-born workers, and there may be large economies of scale in production, so that more immigrant labour can increase economic opportunities for many other workers.

Like any empirical study, the magnitudes of our estimates are specific to our context. The generalisable insights are that the loss of productive immigrant labour can have adverse economic effects on the remaining workers. For policymakers, our results suggest that broad bans and one-size-fits-all policies can have large and detrimental unintended consequences. It would be better to manage and control immigration with nimble and targeted policies that consider the local economic and social structures. Specifically, what do immigrants do? Who will perform those tasks when the immigrants leave, and at what cost? Do the jobs of native workers depend on the presence of immigrants?

Source : VOXeu