Japan and China both faced exposure to Western imperialism in the 19th century, but their responses were starkly different. Japan’s decentralised political system allowed more flexibility in adopting Western technologies and institutions during the Meiji Restoration, whereas China’s centralised bureaucracy hindered significant reforms. This column argues that ideological factors – particularly the willingness to embrace Western ideas – shaped these divergent outcomes by producing a society able to accommodate the massive political and social transformation which accompanied the technological transformation in Japan. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for analysing economic growth patterns across nations.

One of the most important tasks of economics is to deepen our understanding of why some parts of the world are rich and others are poor. In the last century, the most rapid way for countries to grow has been to adopt technologies and institutions employed at the economic frontier. Some countries have been successful in doing so while others have not. What explains these differences in outcomes?

In our recent paper (Ma and Rubin 2024), we distinguish two sources of divergence. Economic divergence prior to and during the Industrial Revolution can be accounted for by several factors studied by the ‘rise of the West’ literature (Mokyr 2010, 2016, Allen 2009, Henrich 2020, Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). But for the period after Britain’s industrialisation, late 19th century Japan and China present a particularly compelling case of rapid catch-up (for Japan) and failure to do so (for China), confronted with a common technological frontier in Britain and the West.

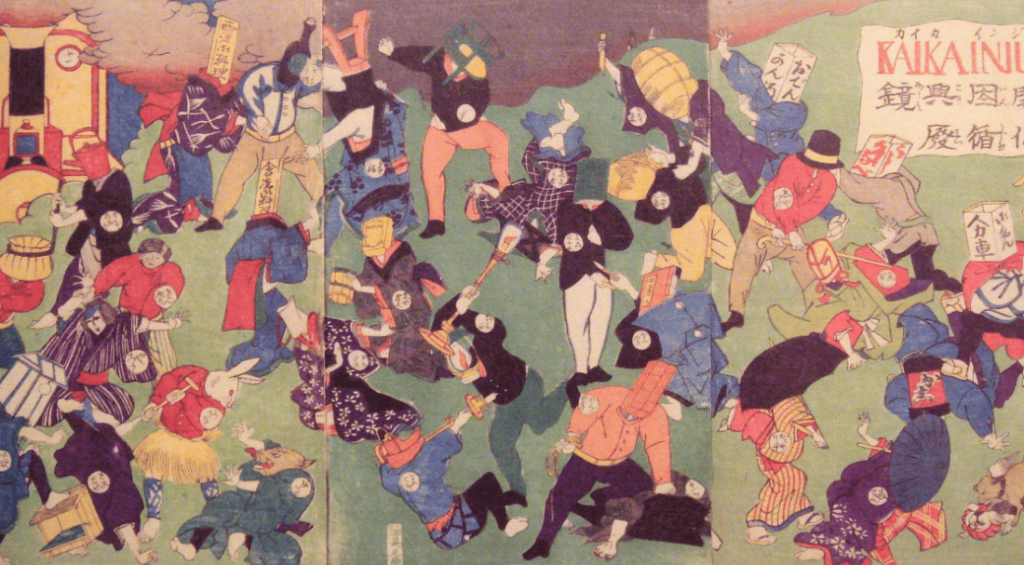

Beginning in 1868, with the onset of the Meiji Restoration, Japan began to modernise its economy in nearly all sectors. By the end of the 19th century, it was on course to develop a highly competitive and modern industrial sector. This process of Japanese industrialisation through systematic learning from the West has been most recently re-examined by Juhász and Weinstein (2024) through the channels of translation in the Meiji era. In the same period, China attempted a ‘Self-Strengthening Movement’ whereby it selectively adopted certain Western capital goods and military technologies but underwent little structural or institutional change (Ma 2021). Over the last three decades of the century, China fell well behind Japan, culminating in its humiliating defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Index of Chinese and Japanese real per capita GDP (1850 = 100)

Note: Data indexed at 100 in 1850 back-projected from the 1930s benchmark PPP adjusted per capita GDP estimates in Fukao et al. (2007). Growth rates for backward projection are from Maddison Project database.

Both reform movements in Japan and China were responses to Western imperialist intervention. But why were the responses so different? While the literature offers several explanations for their differential responses (Ma 2004, Brandt et al. 2014, Sng and Moriguch 2014, Koyama et al. 2018), we argue that ideology played a key role in explaining the reactions of the two nations. We define ideology as “the shared framework of mental models through which one perceives the mapping of inputs to outputs”.

In the cases of Japan and China, the relevant ideologies were those associated with the willingness to adopt from cultures perceived as inferior, the worthiness of Western ‘rational’ education, and the benefits of adopting Western financial and economic institutions. The reason that these outcomes have an ideological component is that they contradicted the traditional Chinese and Japanese view of what was the best way to run a society. Full adoption from the West required more than simply bringing in Western capital or weapons – it required a shift in mindset.

Such a shift in mindset was not trivial. Adopting an alien ideology entailed risks, uncertainties, and learning costs. It may have been possible to observe the superior performance of Western technologies and economies, but it was not so easy to interpret the immediate underlying causes for their performance. It may even have been more difficult to predict the outcome of transplanting Western ideologies and technologies in the Japanese and Chinese cultural context. Ultimately, the Chinese and Japanese would need to adopt Western ideology through their own lens and this would require ingenious reverse engineering. It would entail a process of trial and error that would sort out which elements were key for the desired outcomes and which were simply vestigial appendages.

The closer the two cultures are, the less ‘reverse engineering’ is required, and the more likely it is that reverse engineering will succeed and the associated benefits reaped. In the mid-19th century, China and Japan shared culturally far more with each other than either did with the culturally distant West. This only forces the question: why did the two nations respond differently to the Western challenge given a similar pre-existing cultural and ideological heritage? We argue that among the various factors contributing to the divergence, one key difference was the institutional heritages of Tokugawa Japan and Qing China: a relatively decentralised feudal regime versus a centralised bureaucratic governance structure.

More centralised states will be less likely to adopt new ideologies because of their relatively hierarchical chain of command that tends towards the status quo. Meanwhile, a decentralised governance structure and decision-making process is likely to be far more responsive to new information or exogenous shocks and to coordinate collective action from the bottom up. In the East Asian context, Tokugawa Japan (i.e. prior to the Meiji Restoration) was much more decentralised than Imperial China. Meaningful revolution was therefore more likely to succeed and be less violent although it is slightly ironic that Tokugawa feudalism partly had its ideological roots in Chinese feudalism. While China’s feudal structure had long been supplanted by a centralised governance structure from the medieval period, decentralised feudal rule survived in Japan until the pre-Meiji era.

Our argument yields the following interpretation. Imperial China and Tokugawa Japan were both significantly culturally distant from the West. Yet, the relatively decentralised Tokugawa Japanese political and administrative institutions meant that segments of its society were more likely to respond to the new Western ideology, in turn transmitting a cascade of pressure for change across Japan. This ultimately culminated in the rise of the new Meiji regime (which, ironically, ditched Japan’s feudal past of fragmented rule and decisively re-centralised its governance structure under an imperial system of administrative rule). It was under this centralised decision-making regime that Meiji Japan saw through the transformation instigated by a few aggressive daimyos on Japan’s southern coast who had early exposure and, eventually, appreciation of the full extent of the Western superiority. It gradually but decisively opted for a wholesale adoption of Western ideology followed by subsequent modification, as seen in the widescale adoption of Western financial and economic institutions (see Table 1).

Table 1 Major changes in institutions in Japan

Source: Machikita and Okazaki (2019).

Meanwhile, the Chinese also recognised some elements of Western advancement, particularly its technological superiority. In response, they carried out the ‘self-strengthening’ reform policies under the Tongzhi Restoration of 1862-74. This movement introduced Western military and industrial technology while keeping the traditional economy, administered by powerful Confucian bureaucrats, intact.

The national experiments in both ideology and institutions came to a head in the 1890s. It was Japan’s shocking naval victory in the 1894-95 Sino-Japanese War that gave rise to Qing China’s ideological awakening to Meiji success. The military defeat by what was long regarded as a diminutive pupil was a far greater ideological shock than those inflicted by Western imperial powers, as the prevailing ideology placed China as the dominant power across the world, and especially in East Asia.

Our framework suggests that such an event should have served as a catalyst for an ideological transformation in China which would include borrowing Japan’s successful Meiji reform of both institutions and ideology. Japan’s success – later followed by that of Qing and Republican China – in absorbing Western ideology and institutions relied on conscious ‘reverse engineering’ by tapping into their indigenous intellectual resources. Given the shared cultural and linguistic heritage between Japan and China, the Meiji success in adopting Western ideology and institutions lowered the cultural distance for China to follow suit, since it could ‘reverse engineer’ what Japan had done, as Japan was culturally much closer to China than the West.

Our study places ideology and ideological change at the centre of political and economic transformation. We distinguish it from culture and institutions. Ideology can be an impediment to economic growth, but it can also be transformed or adopted to enable change and growth to occur. Ideologies can change – indeed, China’s market-oriented reforms in the 1970s under Deng Xiaoping represented a massive ideological shift from the Mao regime. Yet, this insight is not a prescription. Like technological adoption, ideological change requires reverse engineering in the local cultural and political context. Instead, this insight is analytical, helping us better understand why some nations have reaped the fruits of the modern economy and others have not. By placing ideology into the framework, our work compliments the much larger study of culture and ideology as represented in the case of religion to economic growth (Becker et al. 2024). Our emphasis on ideology also adds a layer of depth to the recent Noble laureates’s work on institutions (see Dell 2024).

Source : VOXeu