Though news audiences can access a virtually infinite number of opinions, most people see a reduced set of sources controlled by a small number of conglomerates. This column studies guests invited on to French radio and television channels over 20 years, and documents large differences in the coverage of political forces across outlets. Protecting pluralism in the news media requires not only encouraging ownership diffusion across competing outlets, but also ensuring that each outlet features a balanced representation of political forces, thereby setting boundaries on a channel’s editorial policies.

On 19 February 2024, Ofcom – the regulatory authority for the broadcasting industry in the UK – opened a due impartiality investigation into GB News, the overtly right-wing broadcaster launched three years prior (Ofcom 2024). Around the same time, on 13 February 2024, the Conseil d’État – the supreme court for administrative justice in France – ruled on a matter brought by the organisation Reporters Without Borders. The court found that in order to assess a television channel’s compliance with the required “pluralism of information”, Arcom (the French equivalent of Ofcom) must take into account the diversity of thought and opinion represented by “all the participants in its broadcasts (…) and not merely the airtime granted to political figures”. Further, the court ruled that Arcom must reconsider its decision not to take action against CNews, often described as “France’s Fox News”.

These two decisions remind us of the importance of protecting media pluralism, not only by encouraging ownership diffusion across competing outlets (external pluralism), but also by ensuring that each outlet features a balanced representation of political forces, thereby setting bounds to channel editorial policies (internal pluralism). While people can access a virtually infinite number of opinions, reach and attention patterns are such that audiences are actually exposed to a reduced set of news sources, themselves controlled by a small number of conglomerates (Prat 2018, Kennedy and Prat 2019).

In a new paper (Cagé et al. 2024), we study the guests invited by hosts of France’s radio and television channels over 20 years, and document large differences in the coverage of political forces across outlets. To do so, we consider not only news shows and airtime granted to political figures – as is usually done in the existing literature – but all programmes with at least one guest and one host. Further, we classify guests who are politically vocal but are not professional politicians, such as activists, think tank commentators, public intellectuals, etc. We label these guests ‘politically engaged non-politicians’ (PENOPs). Doing so is not an easy task and has become the focus of ongoing discussions following the Conseil d’État’s decision. In our research, we propose a novel approach based on lists of think tank contributors, participants at party events, and public figures who endorse presidential candidates.

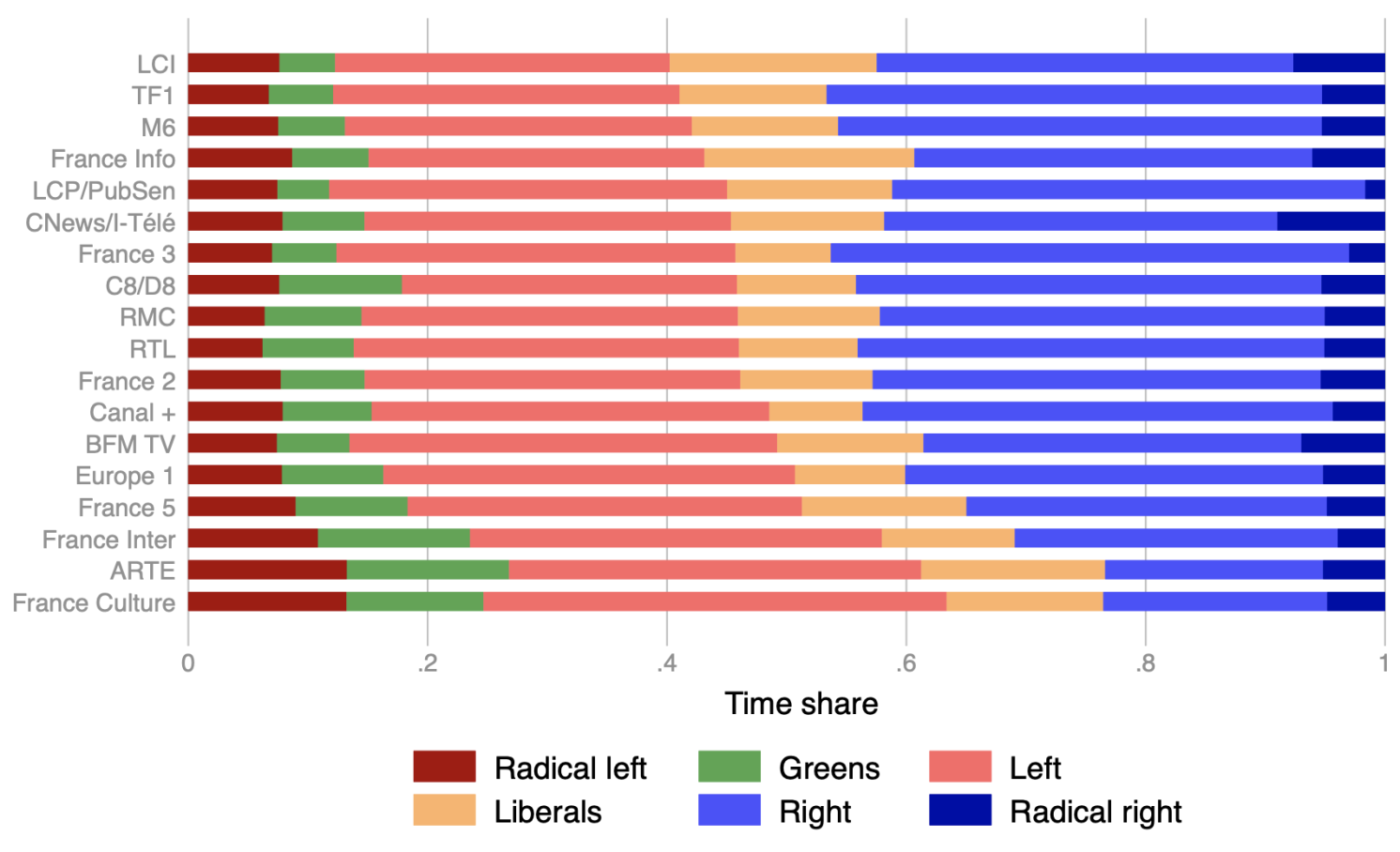

First, we document the fact that political forces are unevenly represented across channels, despite the existence of broadcast regulations meant to ensure respect for pluralist expression. For instance, as shown in Figure 1, on average during our time period, left-wing parties account for around 40% of the speaking time of political guests on the 24-hour news channel LCI, but for more than 60% on the television channel ARTE.

Figure 1 Speaking-time share devoted to different political groups depending on the media outlet

Notes: Figure plots the speaking-time share dedicated to political groups, depending on the media outlet. Media outlets are ranked depending on the time share they devote to left-wing parties.

What drives the differences in political coverage across channels? We seek to measure the relative role played by three factors. First, channels may have distinct editorial policies, to which hosts comply by adapting who they invite depending on the outlet they work for (compliance). Second, channels employ distinct hosts, who may invite different types of guests, potentially due to their preferences or specialisation (composition). Finally, hosts inclined to invite guests from a given group may be more likely to work on an outlet whose editorial line prioritises this group (sorting).

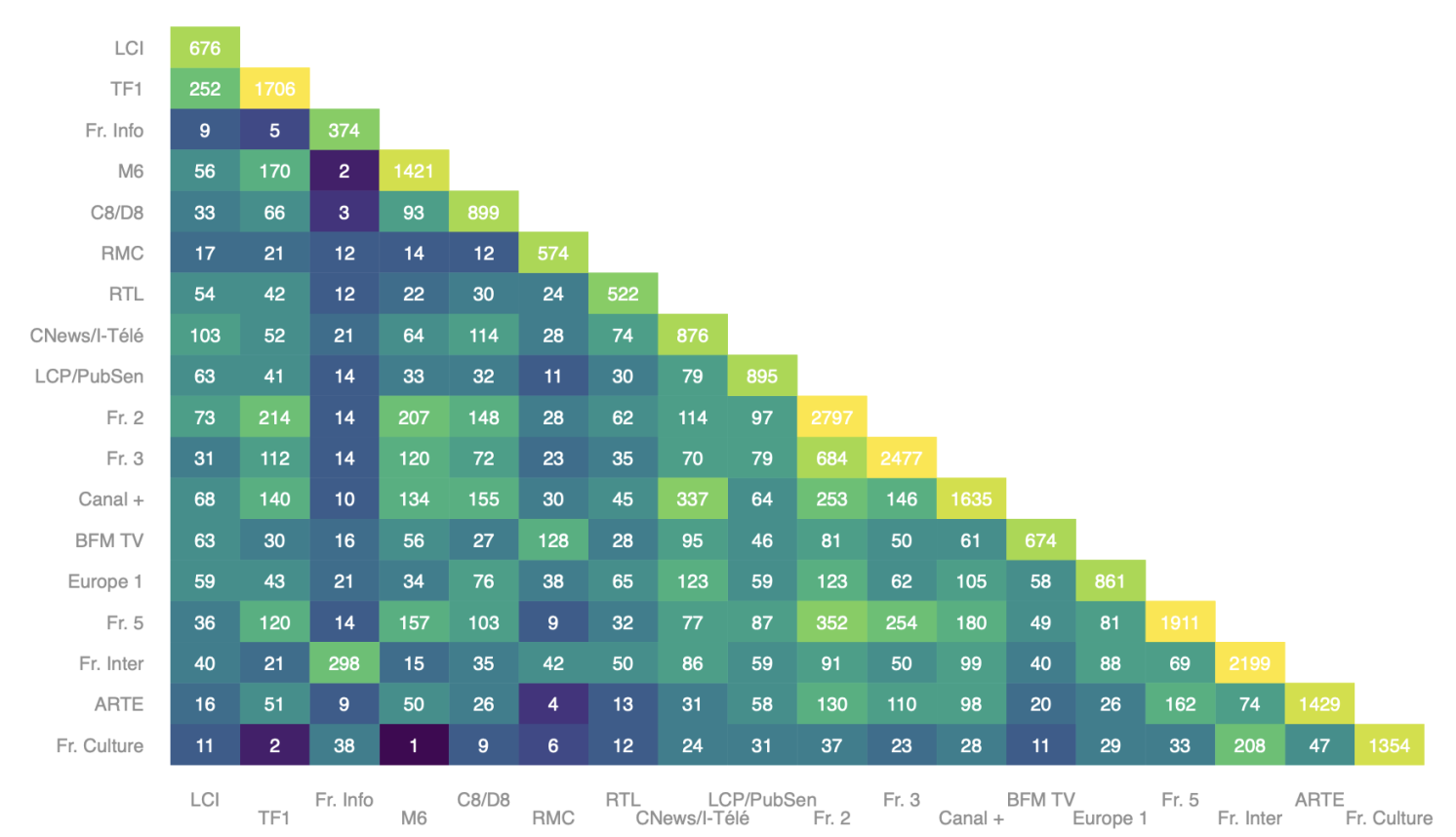

Host compliance with channel-level editorial policies

To measure the relative role played by these factors, we estimate a two-way fixed effects model and assume that the time share dedicated to a political group by a given host on a given outlet at a given time is the sum of (1) a host component – reflecting the host’s baseline propensity to cover a political group; (2) a channel component – accounting for the extent to which a host’s work environment influences how much they cover a certain group; and (3) time components – which capture changes in audience characteristics and news shocks. Channel effects are identified thanks to the 4,456 hosts observed on distinct channels in our sample (Figure 2); they are allowed to change every two seasons to reflect the fact that channels’ editorial lines may be periodically adjusted (Lachowska et al. 2022).

Figure 2 Hosts observed on multiple outlets

Notes: Figure plots, for each outlet pair, the number of distinct hosts observed on both outlets in the estimation sample. Figures on the diagonal report the number of distinct hosts observed at least once on the considered outlet, irrespective of whether they are observed on another outlet.

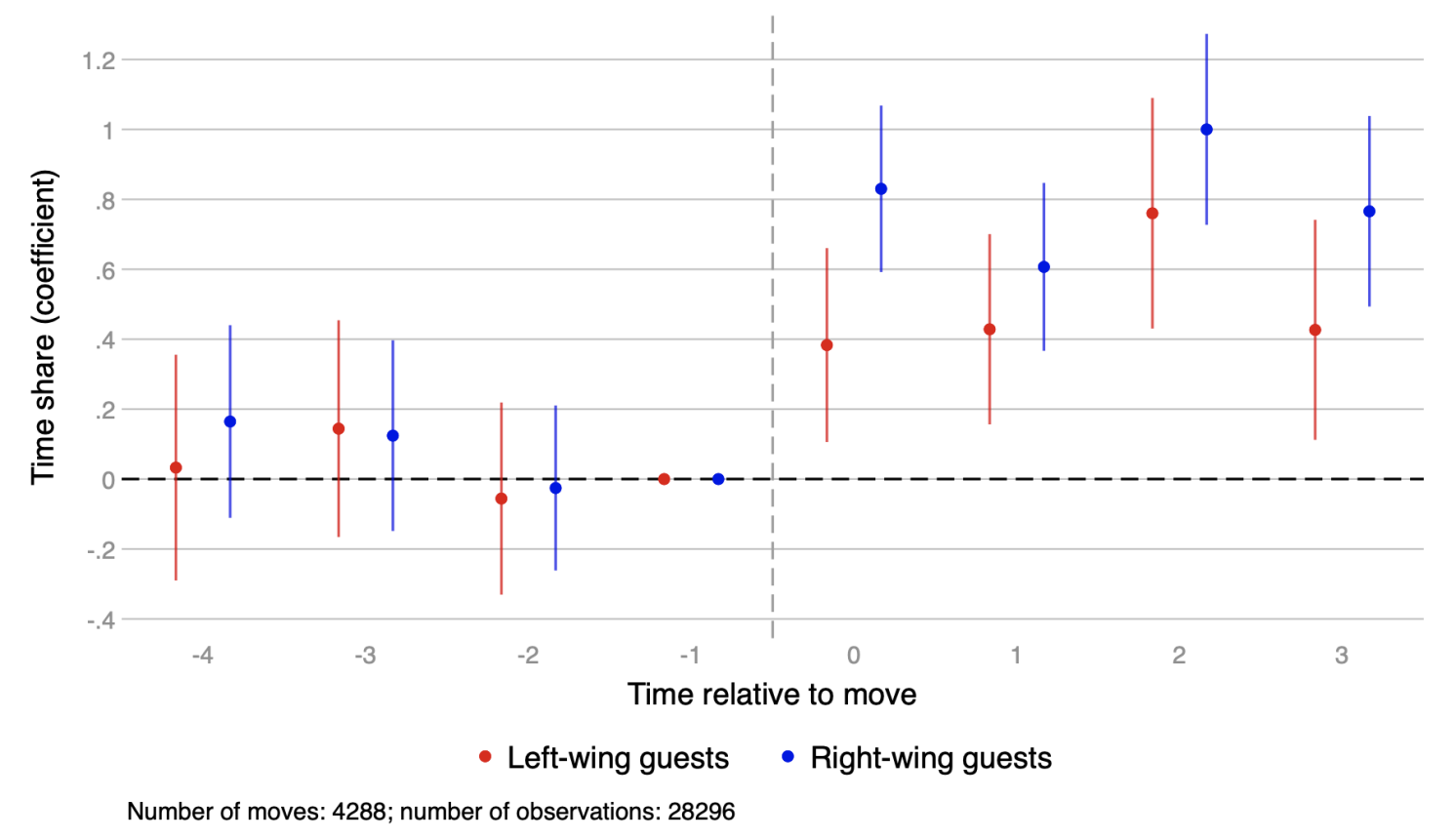

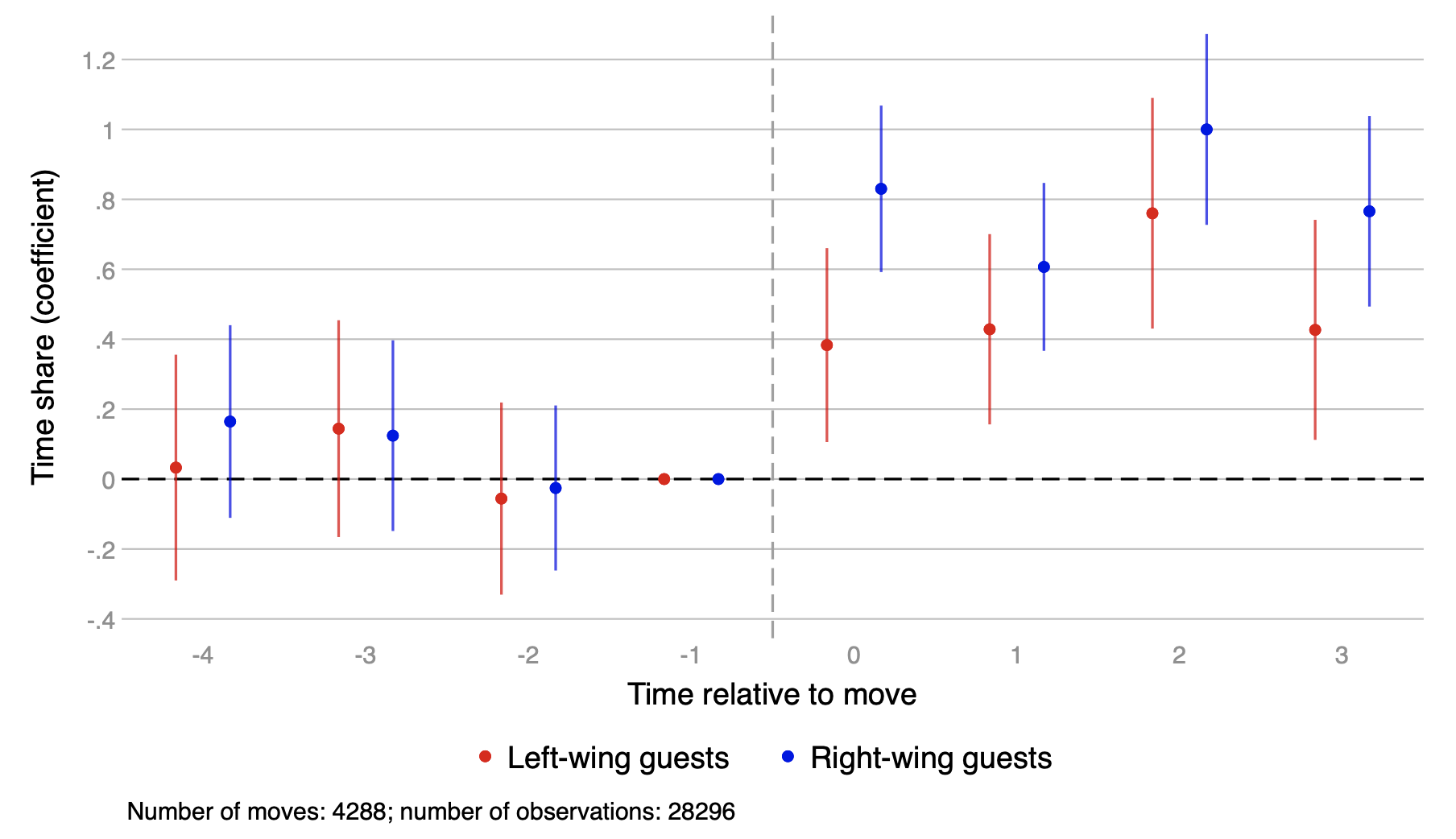

Importantly, we provide evidence of the fact that hosts’ moves can be considered exogenous; in other words, we show that hosts do not switch to another outlet because their preferences change with regard to their choice of guests. To do so, we rely on an event-study specification and compare differences in the channel-level average speaking-time share of a given group between the destination and origin channels with the time share devoted by the host to different political groups. As appears clearly in Figure 3, invitation patterns sharply change after the host’s move, and there is no pre-trend. Hence, moves do not seem triggered by drifting host preferences or by temporary shocks. In terms of magnitude, moving from a channel that devotes 0% of the share of political speaking-time to the right, to a channel that devotes 100% of this share to the right increases the political time share that the host devotes to the right by 80 percentage points.

Figure 3 Event study: Change in the time share devoted to different political groups around the move

Notes: Figure plots event-study estimates. The dependent variable is the time share devoted by a host to a given group in the weeks before and after the move. These shares are expressed as a share of the total speaking time of the political guests alone. Red dots report the time share of left-wing guests; blue squares report the time share of right-wing guests. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors are clustered at the move level.

More technically, following Abowd et al. (1999), we then decompose the variance in political group representation across outlets and periods. The variance of channel components reflects compliance with outlet-level decisions; that of host components accounts for host composition; and the covariance between host and channel effects captures sorting. The first outcome we consider is the time share dedicated to guests of given groups among all guests. Doing so accounts for two decision margins: whether to invite political guests (extensive margin), and if so, of what leaning (intensive margin). After netting out the time effects, we show that channel editorial lines account for around 40% of the differences in guest invitation patterns across channels, sorting accounts for another 40%, and host composition for 20%. Focusing exclusively on the intensive margin – i.e. which political group to represent conditional on having a political guest – we then find that channel-level decisions play an even more important role. Whether we consider the speaking-time share devoted to the left or to the right, we see that channel components account for around 80% of the variance in speaking times once we take into account the time effects. Host composition only accounts for a small share of the variance (less than 10%), just like host sorting. Hosts therefore largely comply with channel-level editorial policies. Furthermore, within owners, outlets tend to prioritise the same political forces, suggesting that the owners want all of their channels to prioritise certain views, probably corresponding to their own preferences.

Adapting to a change in editorial policy: The CNews effect

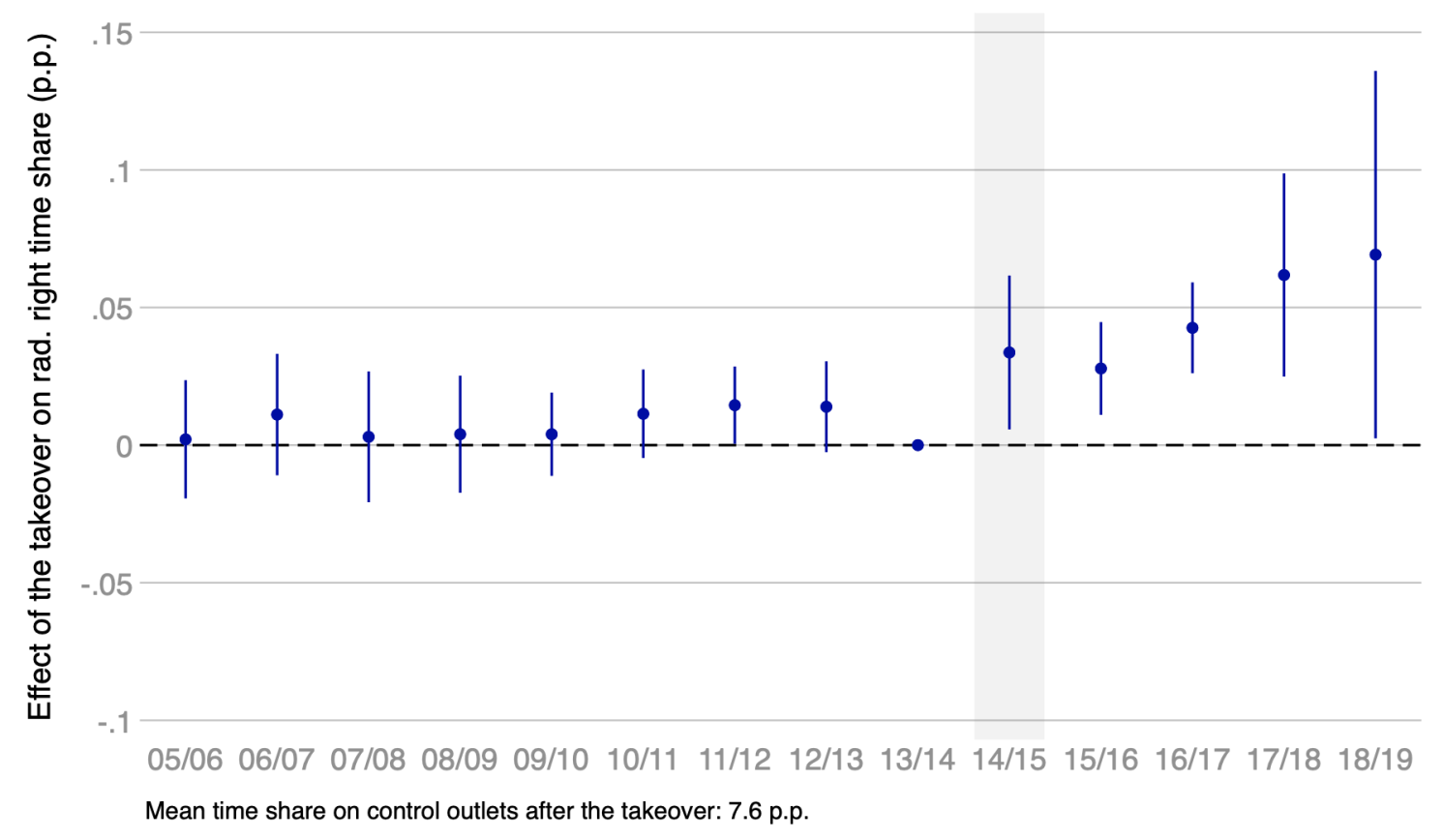

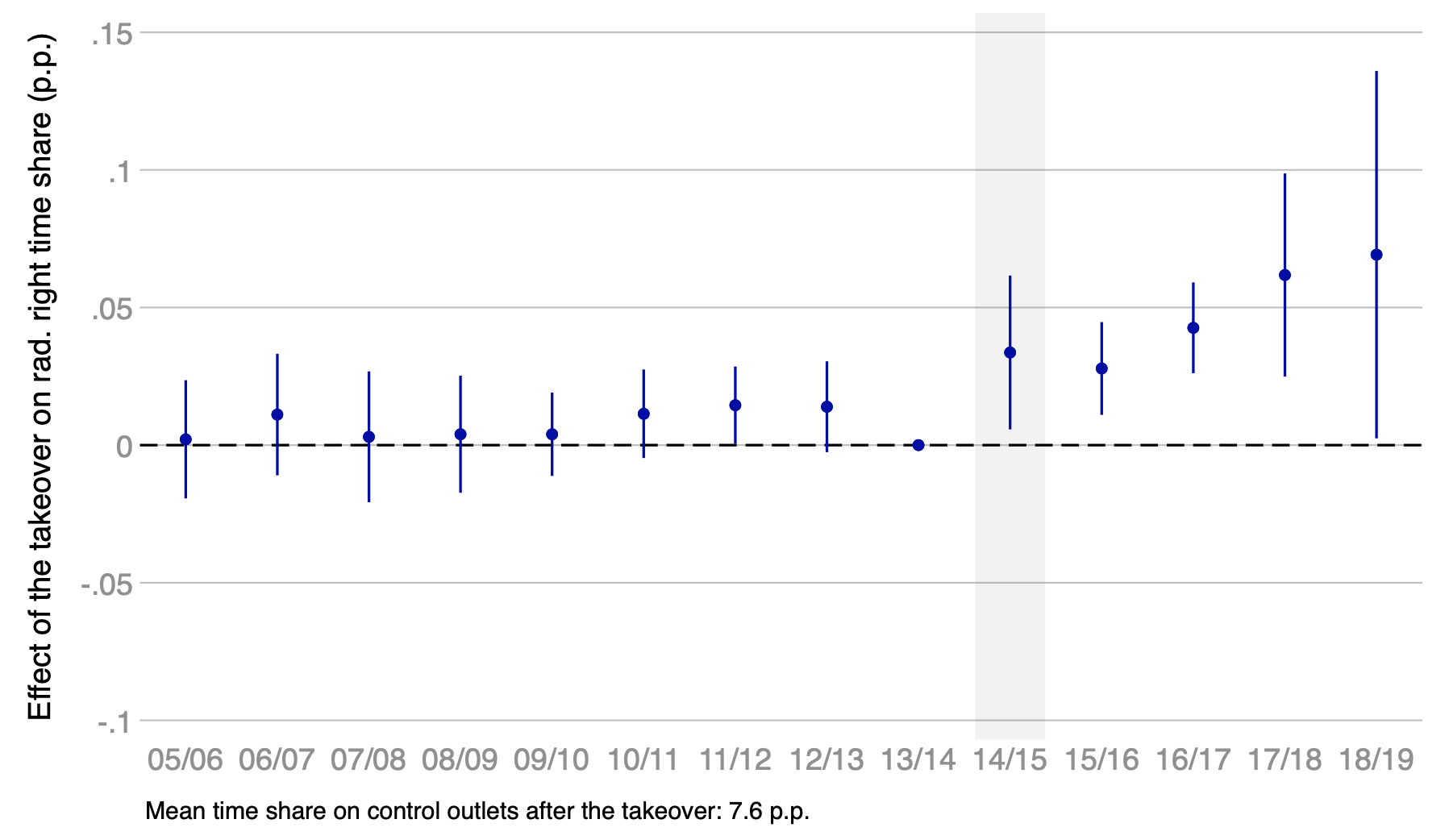

To further document the role played by owners in biasing the news, we then focus on a large owner-induced change in editorial policy. In 2015, Vincent Bolloré – a French billionaire often compared to Rupert Murdoch – became the main shareholder of the Vivendi conglomerate, the parent company of the Canal Plus Group, which owns several television channels. Journalistic accounts of the event have highlighted the proximity of Vincent Bolloré to conservative figures, and noted shows swiftly moved rightwards following the takeover (Capozzi 2016, Cagé 2022). First, we compare Vivendi channels to others in our sample around the takeover to quantify the magnitude of the editorial shift. We show that, controlling for channel and time fixed effects, Bolloré’s takeover led to a 5.53 percentage-point increase in the speaking time of the radical right, compared to a 7.6% baseline on control channels (Figure 4). This change is not entirely driven by hosts being replaced; hosts who stayed nearly fully adjusted their choice of guests to the new editorial policy.

Figure 4 Event-study regression: Radical-right time shares around Bolloré’s takeover

Notes: Figure plots estimates from an event-study specification. The dependent variable is the speaking-time share of radical-right guests (both politicians and PENOPs). The shaded area corresponds to the season running from September 2014 to August 2015, during which Vincent Bolloré took control of the channels. Standard errors are clustered at the channel level, vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

We also show that the magnitude of the shift toward the radical right following Bolloré’s takeover is stronger when PENOPs are included than when we only consider the speaking-time share of strictly defined politicians. This is of particular importance because it suggests that PENOPs may be used by the channels to bypass the existing pluralism regulation and highlights the importance of the Conseil d’État’s decision.

We next analyse whether hosts left the channel in response to the change in editorial policy. We find that the probability that a host stayed decreases by 15 percentage points following the takeover, from a 51% baseline. The effect is driven by hosts who invite political guests, who are credited as ‘journalists’, and whose shows are newscasts. It suggests that hosts who were most exposed to the change in editorial policy were precisely those most likely to leave. Male hosts, famous hosts, and hosts credited as producers were more likely to stay. This is also the case for hosts who already tended to invite more radical-right guests before the takeover and were thus probably more compatible with the new editorial line. Regarding hosts who left, most are no longer observed on any of the channels in our sample following the takeover, suggesting that their career was negatively impacted. Those who work on another channel are more likely to work on a channel that represents the right relatively less, hinting at potential sorting on editorial policy.

Ensuring due impartiality

In conclusion, our findings have important policy implications for the optimal regulation of the media sector. First, when measuring pluralism, it is important to focus not only on politicians narrowly defined as candidates at elections, party officials, and elected politicians. Channels increasingly rely on PENOPs to bias content; by doing so, they avoid existing regulations and may limit the range of views to which voters are exposed. Second, given that the impact of ownership changes on editorial policies varies with the characteristics of the journalists – particularly with their bargaining power – one may want to implement policies to reinforce the agency of journalists. Finally, despite the increasing number of information sources available to the public, rules to guarantee “internal pluralism” or “due impartiality” are still needed. Most citizens get their news from a limited number of sources, which are moreover owned by a small number of companies. Guaranteeing “external plurality” is thus not enough to ensure that citizens are exposed to a plurality of views: the impact of the end of the “fairness doctrine” in the US serves as a stark reminder of this, as seen not only in the rise of Fox News but also in the increasing polarisation of the political landscape.

Source : VOXeu