Are the goals of combating climate change and ending global poverty at odds with each other? This column estimates the economic growth needed to reduce poverty, and the greenhose gas emissions that this growth is likely to generate, to show how the answer to this question depends in part on the evolution of global and domestic inequalities. One way to achieve development and climate goals simultaneously is by reducing inequality and making growth more inclusive.

A recent report by Oxfam finds staggering inequality in global emissions (Oxfam International 2023). The report suggests that the richest 1% are responsible for 16% of global emissions, emitting as much as the poorest two thirds (i.e. 5 billion people, of whom about 700 million live in extreme poverty) (World Bank 2022). Previous studies found similar disparities and sought to bring more scrutiny of the emissions of the richest (Bruckner et al. 2022, Chancel and Piketty 2015, Hubacek et al. 2017a, 2017b, Otto et al. 2019).

Our study

In a new study (Wollburg et al. 2023), we investigate the emissions associated with ending global poverty and raising the incomes of the world’s poorest people and explore how different levels of inequality affects this relationship. We use a different approach from previous analyses: instead of looking at the emissions that would result from the increase in consumption of poor people needed to lift them out of poverty, we estimate the economic growth needed to reduce poverty, under different assumptions on inequalities, and then the emissions that this growth is likely to generate. With this approach, the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions needed to eradicate poverty are larger – since we also account for the impact of economic growth on the emissions of people who are not living in poverty – but it is more realistic, because 90% of historical poverty reduction has come through economic growth (Bergstrom 2022).

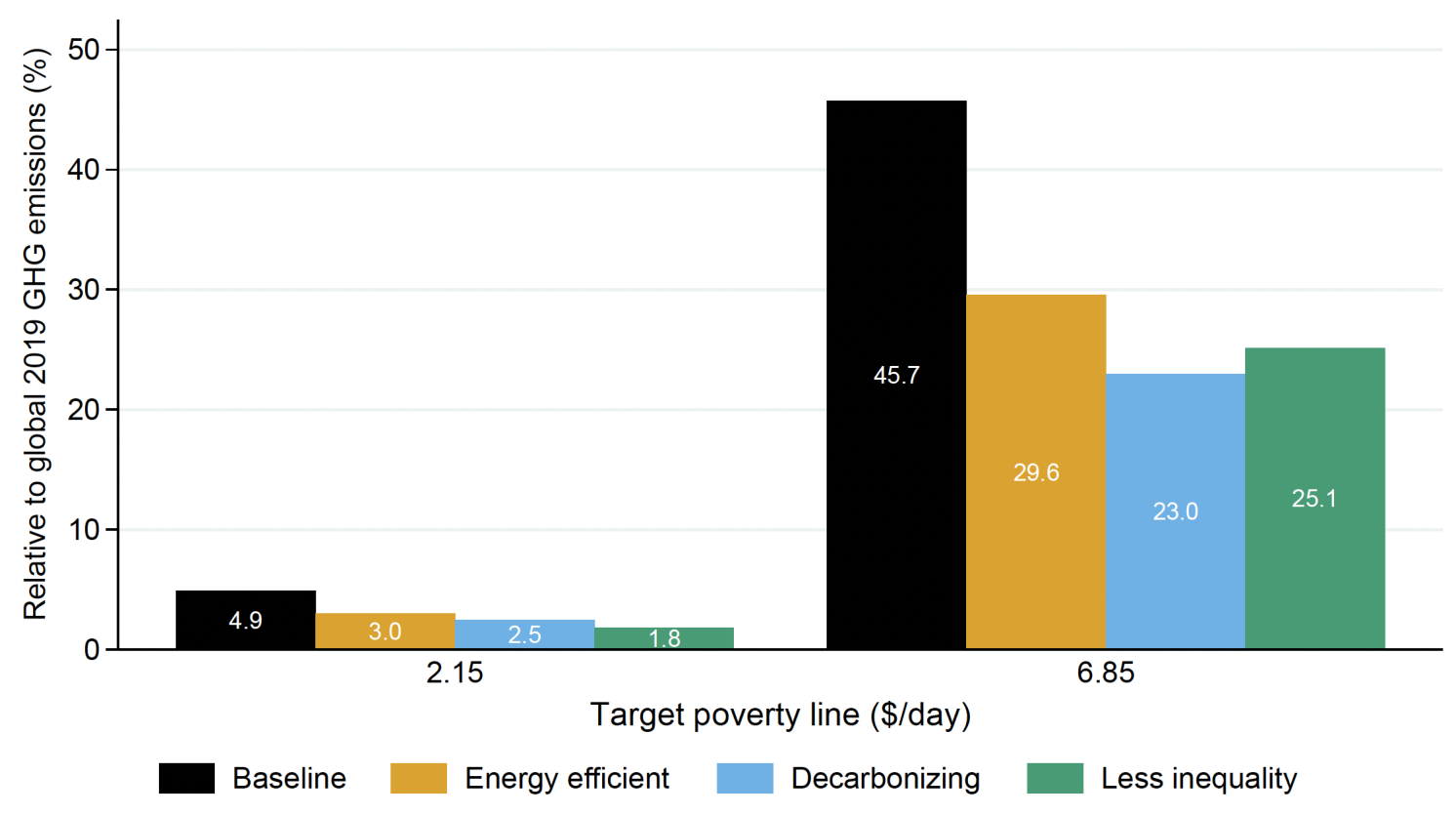

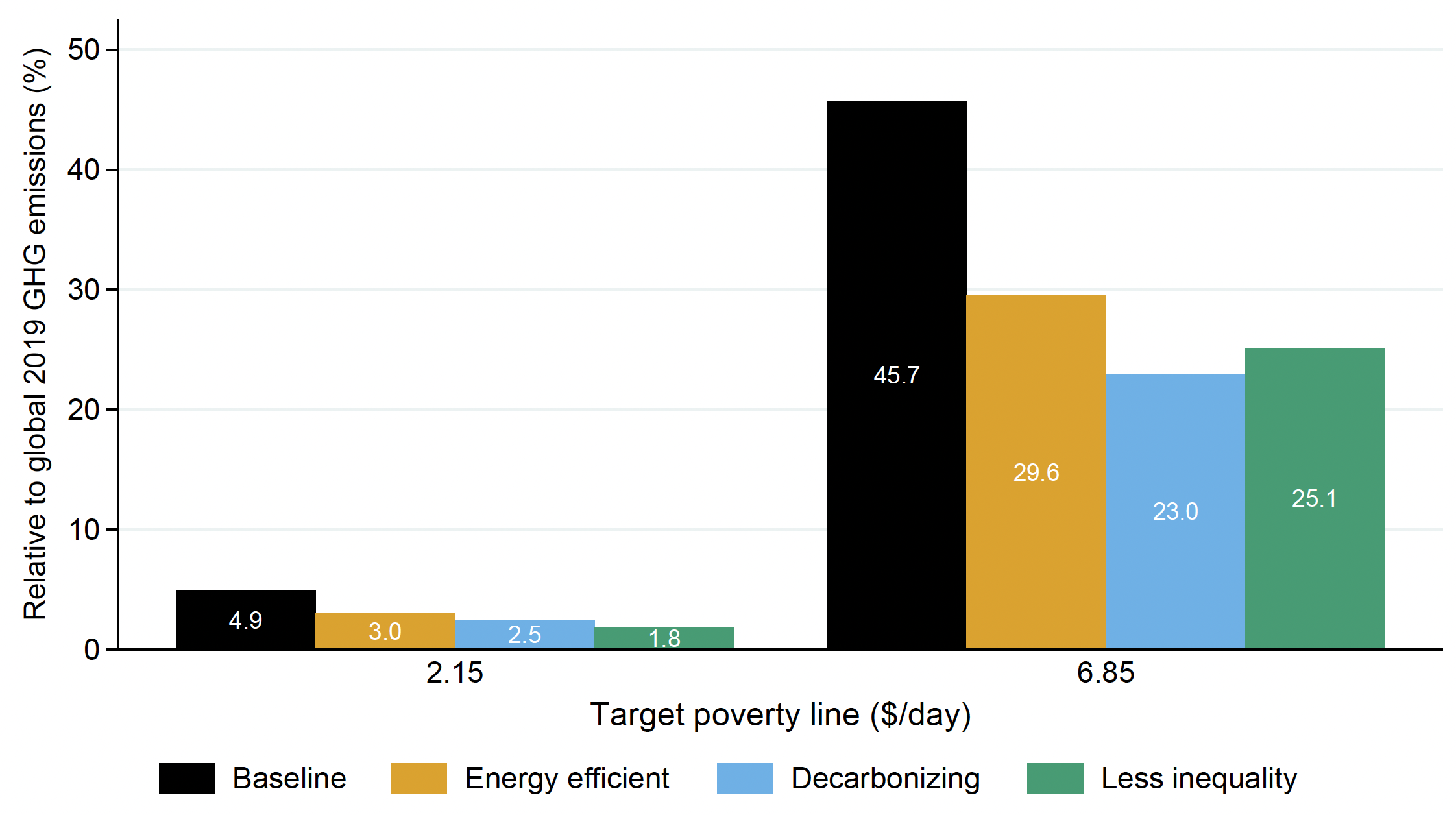

We show that, even with the energy and carbon intensity patterns of the past 20 years, the emissions of ending extreme poverty using the international poverty line of $2.15 per day are limited to 2.37 Gt of CO2 emissions per year or 4.9% of 2019 global emissions. This is small: ending extreme poverty and limiting global warming are not at odds and it is misleading to present the climate change challenge and ending extreme poverty as a trade-off. This is because poor countries emit very little, and the accelerated growth needed to eradicate poverty in these countries would generate less additional emissions than the richest 1% emit. What is more, poverty eradication and reducing GHG emissions are even less of a trade-off if one considers the high vulnerability of poorer people to climate impacts and how climate change threatens poverty reduction (Jafino et al. 2020, Lankes et al. 2024).

Using a higher poverty line

However, things are harder when we use a poverty line typical of upper-middle-income countries (i.e. $6.85 per day). There are currently over three billion people living below this standard, and most countries have not met it. The emissions from the economic growth needed to bring everyone to at least $6.85 per day with historical energy- and carbon-intensities are much higher at 22.1 Gt per year, or 45.7% of 2019 global emissions. This result shows that we cannot provide middle-class standards of living to all with historical technologies and inequalities without compromising our climate goals.

One way to reconcile this tension is for countries to develop with radically improved energy and carbon efficiency. If countries adopt the energy and carbon intensity of the historical best performers, the emissions needed to reach a minimum of $6.85 per day for all would be reduced by 35-50%. Furthermore, with the rapid progress in green technologies – from solar panels and electric mobility to climate-smart agriculture practices – it is even possible to do much better today than the historical best performers, often at a negative or negligible cost. Though poorly designed policies, or policies that are not supplemented with action to protect poor and vulnerable people, can hurt low-income households (Känzig 2023), a rapidly growing body of evidence, as well as ex-post studies of climate policies, shows that the two goals can be complementary (World Bank 2023, Lankes et al. 2024).

The effect of reducing inequality

Another way to achieve development and climate goals simultaneously is by reducing inequality and making growth more inclusive. In our paper, we show that if all countries reduce inequality at the rate of the top 10% historical Gini declines between 2022 and 2050 – a reduction of around 17% – the emissions associated with ending poverty at the poverty line typical of upper middle-income countries falls by around 50%. The reason is simple: if inequality is reduced, the poor are moved closer to the poverty line, and hence less growth is needed to alleviate poverty. By contrast, if inequalities in countries increase, which could happen due to unequal exposure to climate change (Coronese et al. 2022), more growth and more emissions are needed to end poverty.

Figure 1 Emissions needed to end poverty under various scenarios and poverty lines

Higher income countries also have a role to play. Though inequalities between countries have fallen (Wills and Mayhew 2020), they remain large, and wealthy countries have the greatest capacity for effective global climate finance (Chancel et al. 2024). Financial resources transferred from rich to poor countries through development assistance can accelerate poverty reduction in developing countries, while ensuring these countries can access the green technologies they need to grow fast and grow clean. And of course, rich countries can reduce their emissions faster. We show that if non-poor countries increase their rate of decarbonisation by just 0.28% annually towards 2050, they can fully offset the emissions needed to end extreme poverty. It would take twice the effort by poor countries.

Source : VOXeu