The issues of whether and how banks penalise climate risk in their lending activities, and how monetary policy affects this, are key for policymaking. This column uses credit register data for euro area banks and carbon emission data for firms to show that banks charge higher lending rates to high-emission firms and lower rates to those that commit to reducing their emissions in the future. The authors also find evidence of a ‘climate risk-taking channel’, with monetary tightening constraining lending conditions relatively less for green firms.

Do banks penalise climate risk in their lending activity? If so, does this apply particularly to banks publicly committed to low-carbon targets? Does monetary policy affect the climate risk premium required by banks? These are key issues for policymaking, considering that the ECB is committed to taking climate risk into account in its supervisory framework (ECB 2020) and stress tests (ECB 2022) and climate change in its monetary policy framework (ECB 2021). However, there is no consensus in the literature on the answers to these questions. So far, for example, the evidence on whether banks price climate risk in their lending policies is far less clear-cut than that regarding the pricing of climate risk in bond and stock markets (Beyene et al. 2021, Ehlers et al. 2022, Degryse et al. 2021). There are also different views on whether the disclosure made by banks on their commitment to decarbonisation is reliable (Kacperczyk and Peydro 2021, Giannetti et al. 2023). Another key question which is until now totally unexplored is whether changes in monetary policy affect the climate risk premia charged by banks to polluting firms. In a recent paper (Altavilla et al. 2023), we combine granular credit register data for euro area banks and firms’ carbon emission data to address these related questions.

Whether banks should care about climate risk in their lending policies is not obvious. In principle, they should care about climate risk only insofar as it affects their clients’ default risk. For instance, a bank lending to an oil company should take into account the risk that carbon taxes or environmental regulations may end up forcing the company into default. However, the models that banks use to assess credit risk may not fully capture tail-risk events such as future changes in regulation or technology. Moreover, these models may fail to capture the systemic risk arising from adverse environmental shocks or unforeseen changes in carbon taxes, and the resulting concerns of macroprudential regulators. Last but not least, banks may internalise social concerns about climate risk for reputational reasons, in response to pressure from the media, depositors and activist shareholders.

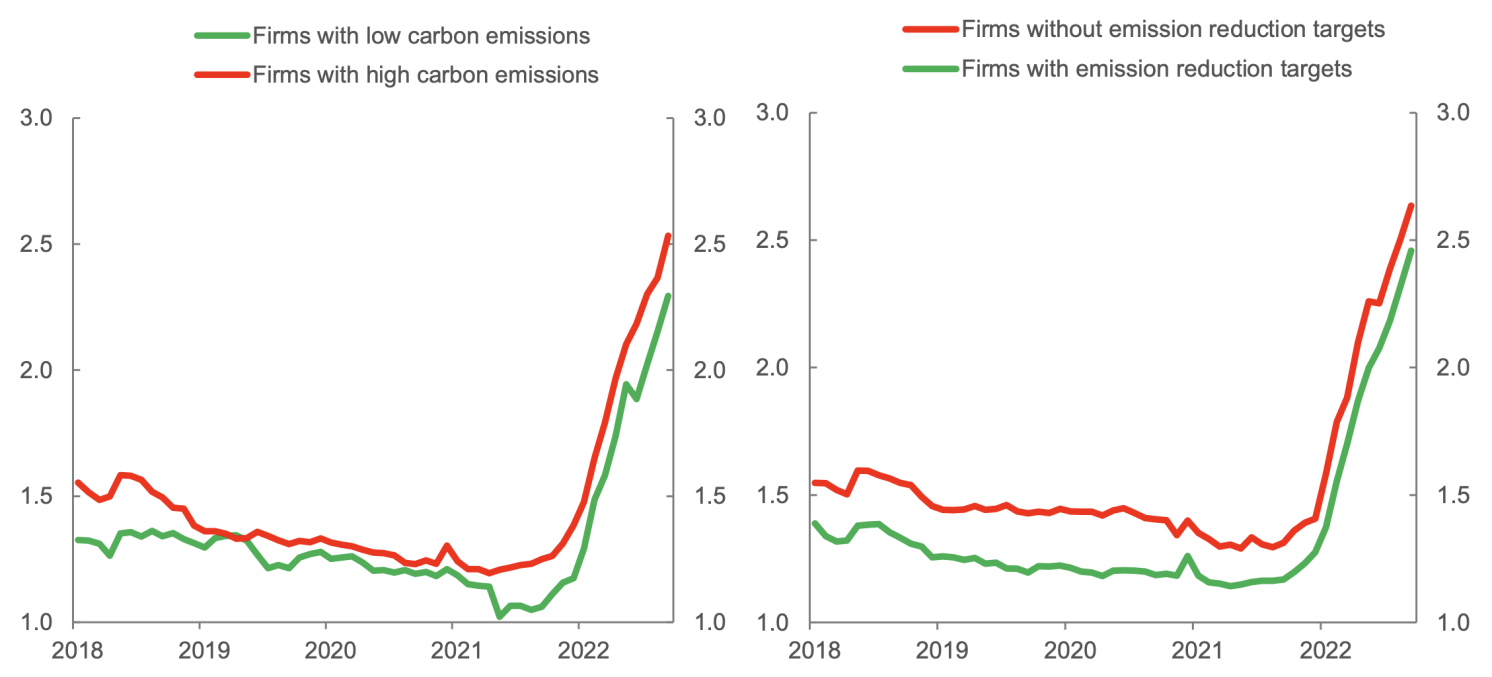

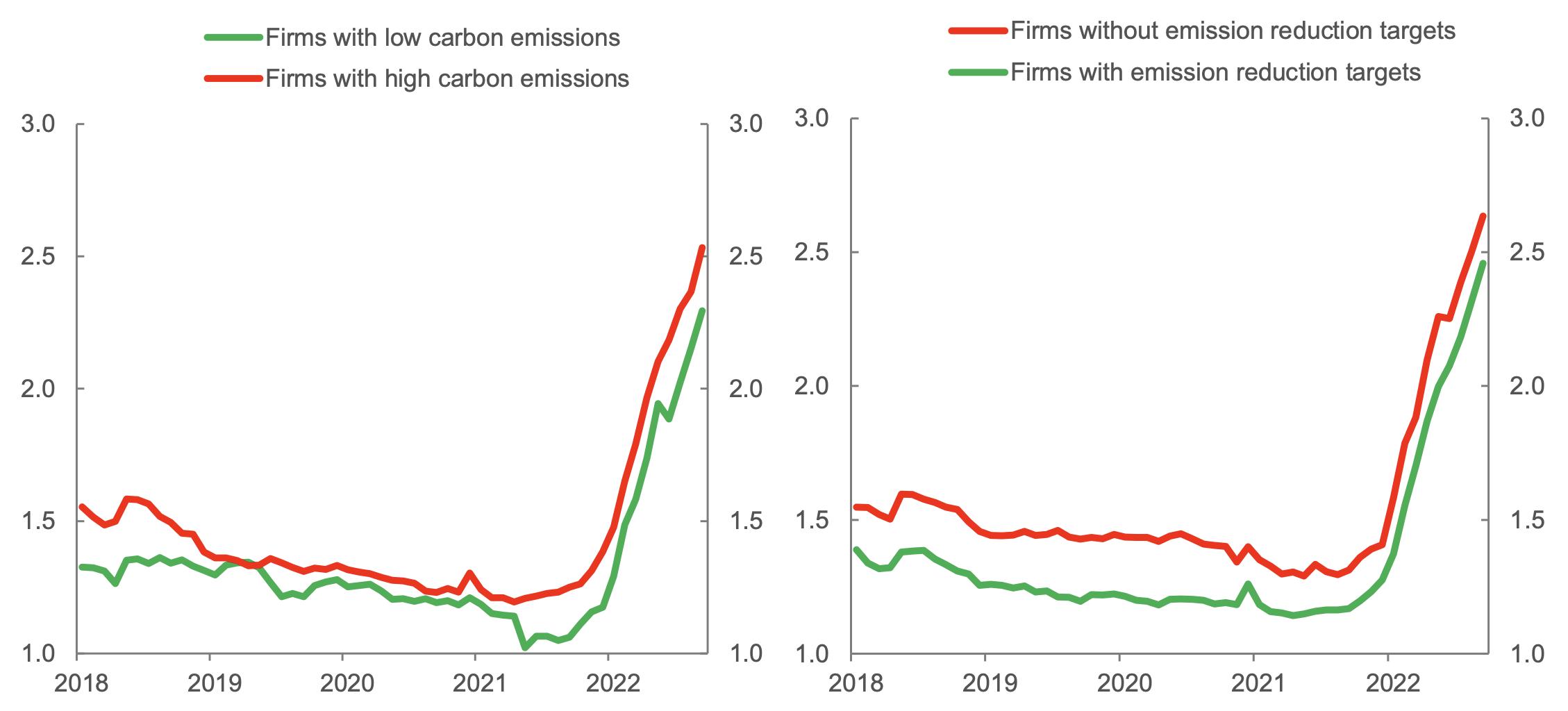

However, media attention and investors’ activism may be less successful in affecting banks’ environmental record than that of, say, a mutual fund or a pension fund, because banks’ loan portfolios are typically far more opaque than the securities portfolios of institutional investors. This probably explains why the evidence on the pricing of climate risk in bank loans is not well established. Figure 1 suggests that euro area banks do price climate risk: the monthly mean interest rate charged to firms in the top quartile by current carbon emissions consistently exceeds that charged to firms in the bottom quartile. The difference between the two is close to 15 basis points, on average (left chart). Moreover, the rate that banks charge to firms that have not committed to reducing future emissions consistently exceeds that charged to committed firms, with the overall difference averaging 20 basis points (right chart). Hence, banks appear to differentiate their lending rates also based on their clients’ prospective carbon emissions, not just their current ones.

Figure 1 Interest rates charged to green and brown firms

Notes: Average interest rates charged to firms with high-emission and low-emission firms (left panel) and to firms non-committed and those committed to lower carbon emissions (right panel).

The empirical analysis confirms, that controlling for firms’ probability of default, euro area banks charge a higher interest rate to firms with higher current carbon emissions and a lower rate to those that commit to reducing their emissions in the future. These results are true also within clusters of firms in the same industry, location, and size class and even when controlling for any time-invariant firm characteristic. We also find that banks that publicly commit to low-carbon targets lend consistently with such commitment: committed banks charge a higher climate risk premium to high-emission firms and give a larger discount to firms that commit to lowering their future emissions.

Our second research question is whether changes in monetary policy affect the climate risk premia charged by banks to polluting firms. This is an even less obvious question and is still unexplored. Two standard models of the effects of monetary policy on financial intermediation yield opposite predictions. On one hand, models of the risk-taking channel of monetary policy can be extended to encompass climate risk. These models predict that expansionary monetary policy induces banks to reduce monitoring efforts and lend to riskier borrowers, engaging in yield-seeking policies, while restrictive monetary policy has the opposite effect (Acharya and Naqvi 2012, Adrian and Shin 2009, Borio and Zhu 2012, Dell’Ariccia et al. 2014). Extending these models to climate risk, a monetary expansion should lead banks to lower the climate risk premium they charge to high-emission firms relative to low-emission ones, and a monetary restriction should induce banks to raise this premium. In this framework, a monetary easing would favour relatively more brown firms through a ‘climate risk-taking channel’. Symmetrically, a monetary tightening would constrain lending conditions relatively less for green firms. On the other hand, firms with a larger carbon footprint typically have more tangible capital than low-emission firms and therefore can offer more collateral to banks (Iovino et al. 2023). Thus, to the extent that monetary policy affects more credit extended to collateral-constrained firms (Bernanke and Gertler 1989, 1995), one may expect restrictive monetary policy to curtail the debt capacity of low-emission firms more than that of high-emission ones, and symmetrically expansionary monetary policy to facilitate lending to the former more than to the latter. Hence, insofar as low-emission firms are more financially constrained than high-emission ones, the contractionary effect of a monetary tightening should be larger for green than brown firms. This is exactly the opposite prediction to that implied by the risk-taking channel of monetary policy.

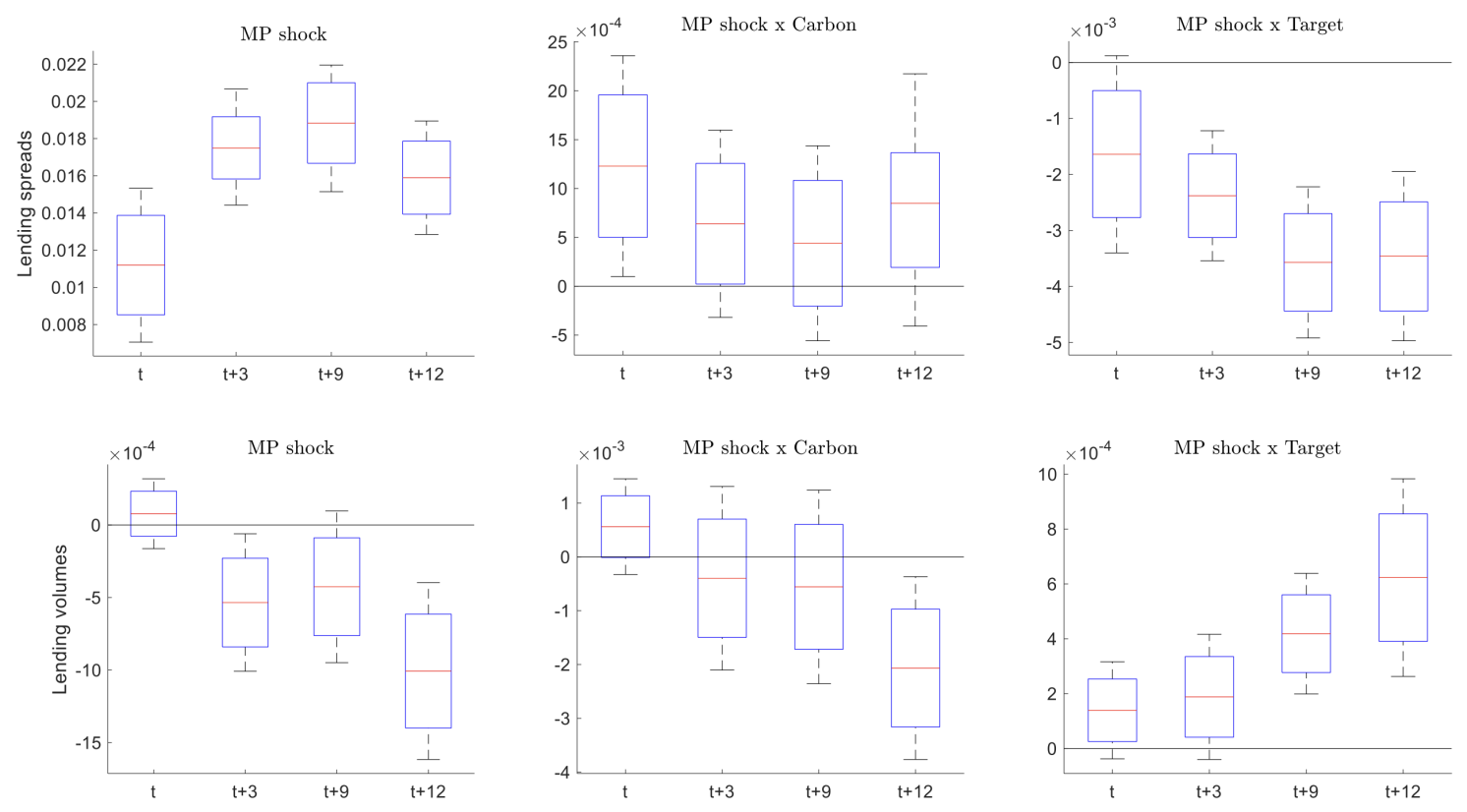

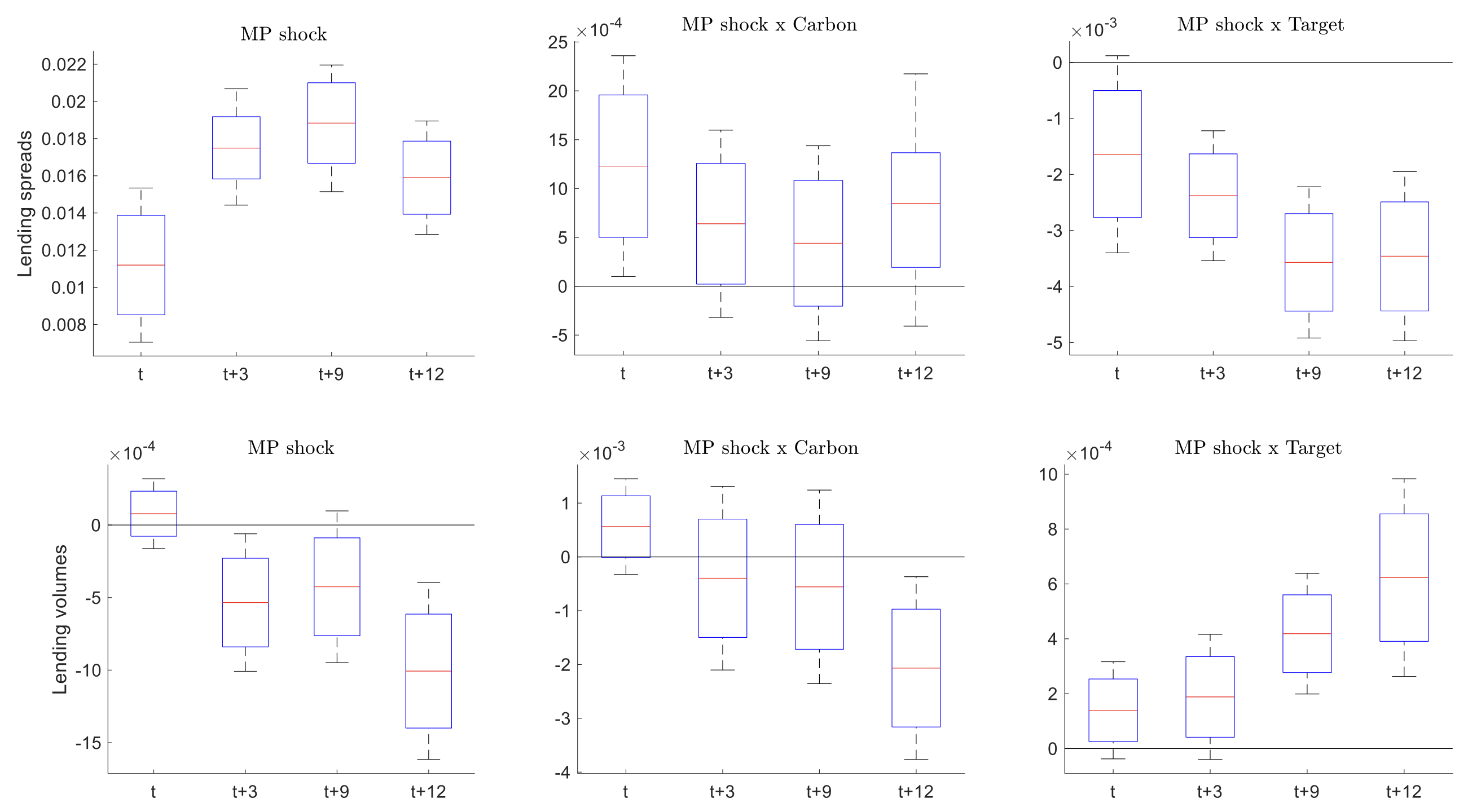

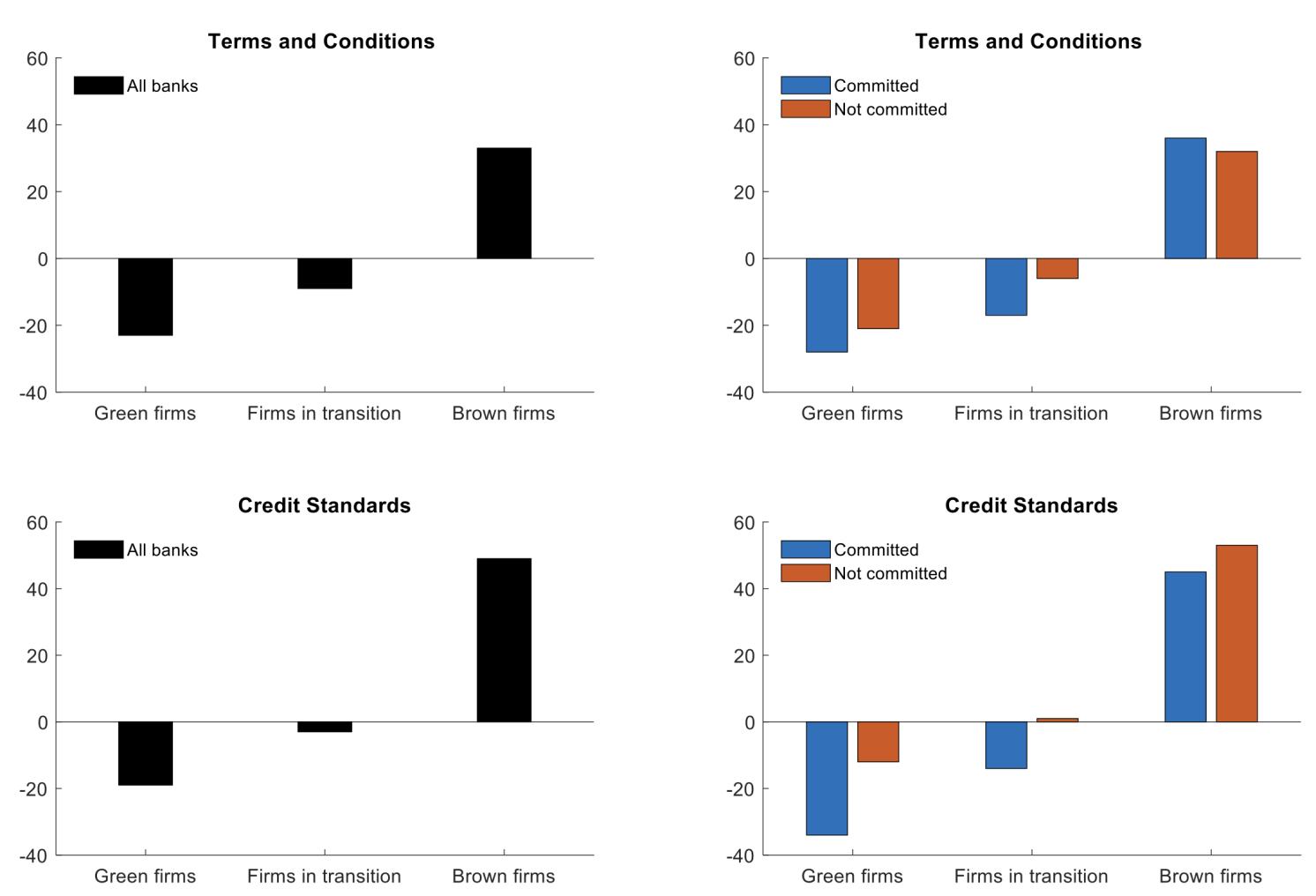

Our evidence on the effects of monetary policy strongly supports the first view: it uncovers a climate risk-taking channel of monetary policy. As shown in Figure 2, unexpected increases in the ECB’s policy rate are associated with an increase in the climate risk premium charged to high-emission firms, over and above the baseline increase in risk premium. Moreover, such restrictive monetary policy shocks are associated with a smaller increase in the climate risk premium charged to firms that are committed to lowering their emissions. Symmetrically, over the subsequent year they result in a significantly greater contraction of lending to high-emission firms than to low-emission ones, and in a lower contraction of lending to firms that commit to a target level of emissions.

Figure 2 Interest premia and loan volumes response to a restrictive monetary policy shock

Notes: The top charts show the dynamic response (upon impact, after three, nine and twelve months) of interest rate premia, and the bottom ones show the dynamic response of the log of loan volumes to an increase in the ECB policy rate, estimated with local projections. The charts in the first column show the baseline responses of premia and volumes, the second column shows the differential response of premia and volumes for high-carbon firms, and the charts in the third column show the differential response of premia and volumes for firms that have an emission target.

These findings are highly relevant to assess the environmental effects of the current monetary policy stance of central banks. Of course, the findings do not amount to saying that a monetary restriction is good for the environment: restrictive monetary policy generally tightens financing conditions, and thus will also slow down investments aimed at reducing carbon emissions (Levine et al. 2018). However, our evidence suggests that a monetary tightening worsens financing conditions more for high-emission firms and for those that are not committed to reducing them. While policy tightening may slow down the pace of decarbonisation, it does not tighten financing conditions as much for firms that are greener or committed to becoming greener.

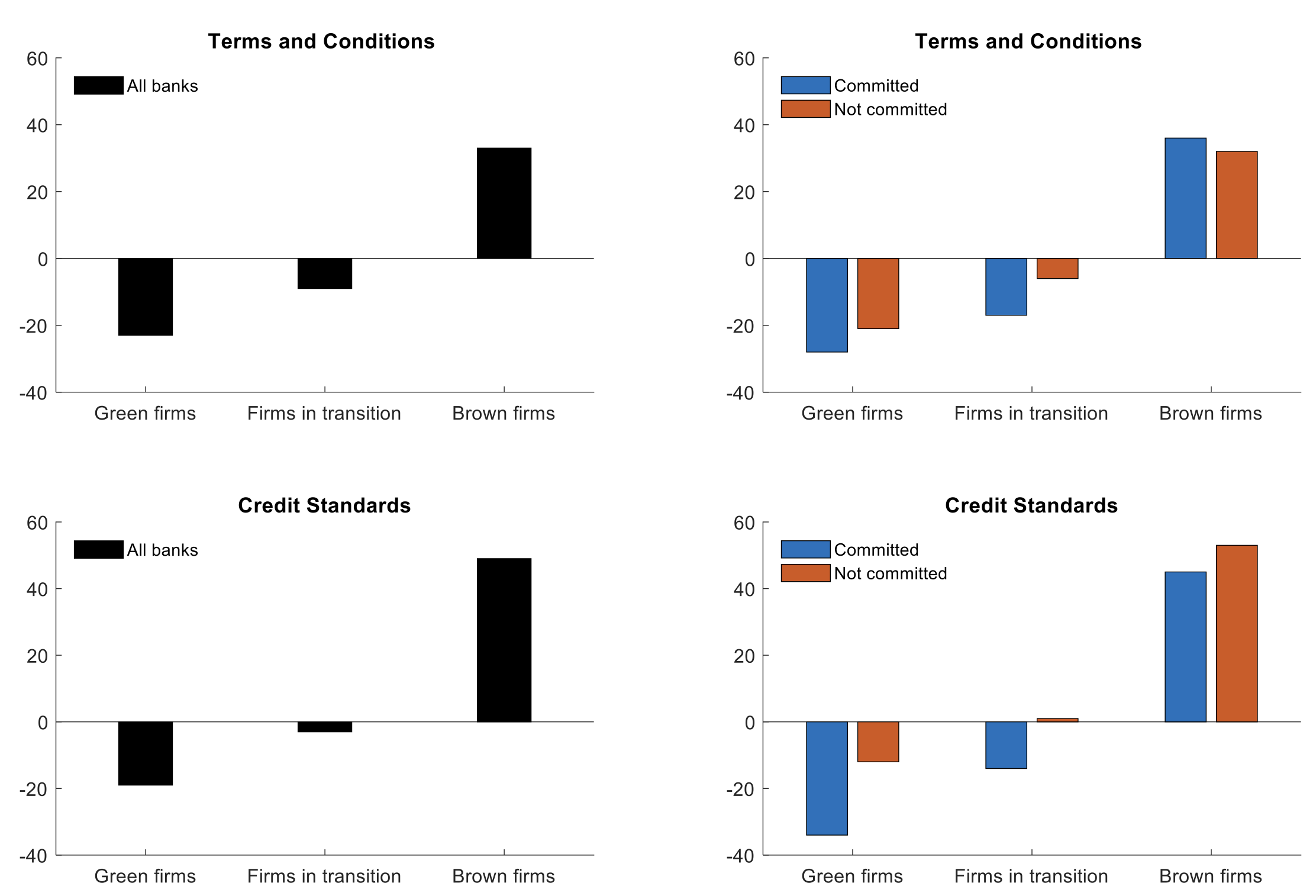

Survey-based evidence provides a consistent picture of the impact of climate risk on bank lending to firms in the euro area. The July 2023 round of the Bank Lending Survey (BLS) scrutinised euro-area banks about the impact of climate change on their lending policies. July 2023 is a particularly interesting date for our purposes since it came after a year of increasingly restrictive monetary policy stance by the ECB. The questionnaire responses indicate that banks tightened their credit standards as well as terms and conditions to firms between July 2022 and July 2023, but their tightening differentiates between “green firms”, “firms in transition” and “brown firms” in a way that is very consistent with our estimates. First, as shown in the top left panel of Figure 3, firms’ climate risk had a net easing impact on their terms and conditions for loans to green firms and firms in transition, while it had a net tightening impact for loans to brown firms. Second, as shown in the top right panel of the figure, banks committed to decarbonisation amplified these changes: climate risk had a stronger net easing impact for green firms and firms in transition for committed banks than for other banks. Symmetrically, for committed banks, climate risk had a stronger net tightening impact on loans to brown firms. Results are similar when we look at credit standards in the two bottom figures.

Figure 3 Attitude by banks towards green and brown firms: Survey evidence

Notes: Net percentages of banks reporting changes in terms and conditions or credit standards in the past 12 months, based on the July 2023 BLS Survey.

Source : VOXeu