They’re universal human aspirations: A world without poverty. Rising living standards. A livable planet. At the start of this century, all of it seemed attainable—within just a few decades.

In 2000, leaders of nearly 190 nations resolved “to spare no effort” in pursuit of those goals. Over the next eight years, the world economy went on a winning streak: Average global growth surged to its highest pace since the early 1970s, boosted by the rapid acceleration of trade and investment in developing economies. Extreme-poverty rates plummeted. A majority of developing economies also improved their monetary and fiscal policy frameworks, which enabled them to emerge from the global financial crisis relatively unscathed. Because of strong global cooperation, the debt burdens of the poorest countries began to shrink.

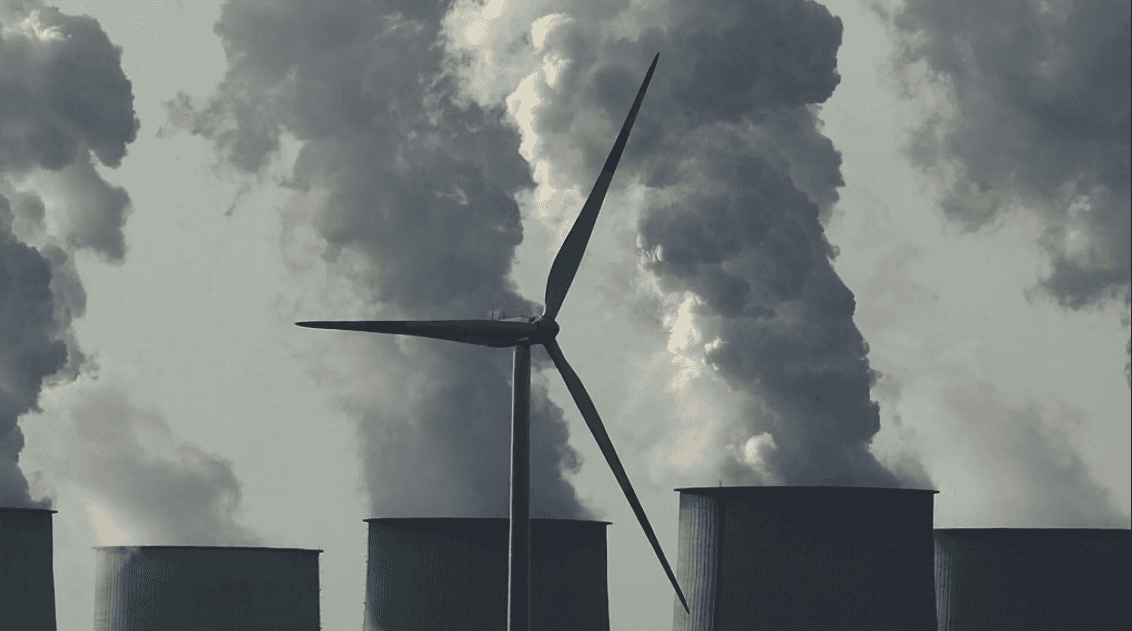

Then things started to go awry. The global financial crisis was followed by a decade of slowing growth—a trend intensified by a series of unprecedented shocks starting with the Covid-19 pandemic. Today, despondency has set in. Policy makers today confront a mutually aggravating cluster of challenges: climate change, food insecurity, and poverty. The price tag for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 has soared, to $4 trillion a year—up nearly two-thirds from 2015. The steeper costs reflect more than a decade of underinvestment: the boom that once powered so much progress has fizzled. At current trends, investment growth in developing economies this year and next is expected to average 4.2%—less than half the average of the early 2000s.

Global trade and foreign direct investment flows have also weakened substantially since the global financial crisis. Global trade is expected to grow less than 2% this year—not even half the annual average that prevailed in the 2000s. At the end of 2022, the total volume of global FDI inflows was down by almost 40% from the 2007 peak. FDI is flagging in precisely the parts of the world that need it most: Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa each picked up just about 5% of the investment flowing to all developing economies over the past decade.

Besides stable prices, investment and trade are the critical building blocks to reduce poverty and increase shared prosperity. They can make people and businesses more productive, enabling gains in both wages and profits. A surge in credit—specifically, access to low-interest loans—is expected to fuel productive investment. After 2010, however, such investment was the exception. Easy money often encouraged debt accumulation and consumption instead of productive investments in many developing economies.

The implications are obvious: without a concerted effort to ramp up investment and trade, the global goals will be unattainable. So far, policy makers have not been able to mobilize the two strongest mechanisms to generate the outcomes they seek with respect to poverty, prosperity, climate, and other key development goals. The appetite for multilateral cooperation has diminished: major economies today are resorting to measures that are fragmenting trade and investment networks. In developing economies, there is little sign of domestic reform momentum that fueled the winning streak of the early 2000s.

This malaise must be overcome. Just as it was in the early 2000s, productive investment in developing economies can be boosted with the right mix of policies and global cooperation. Given the large needs in digital technologies and clean energy, stepping up investment in these sectors could yield big long-term payoffs for developing economies.

A good starting point would be for governments to improve the business environment. History shows that bursts of reforms to improve the business climate tend to coincide with noticeably higher investment growth. They also come with other benefits. Among other things, they stoke job creation and encourage more people and businesses to participate in the formal economy. Strengthening property rights and reducing startup costs can also encourage private investment.

But developing economies alone cannot promote trade and investment while also making meaningful progress on broader challenges of climate change and other development goals. They will need help from abroad to mobilize the necessary public and private capital. International financial institutions can play a major role here—not only by providing financing but also by delivering policy advice that helps them achieve national as well as global development goals.

The global economy of the next 20 years will bear little resemblance to that of the past 20 because nothing less than a radical transformation is underway. The world population is aging at a pace without precedent. Digitalization and generative artificial intelligence are opening up avenues that seemed inconceivable only a few years ago, and are likely to change the world faster than did electricity and information technology. Climate change is already altering the way energy is produced and consumed.

Amid these shifts, future growth need not come from the same sources. At current trends, the global economy’s potential for growth through 2030 is just 2.2% a year—the lowest rate since the 2000s. World Bank research shows it can be accelerated above previous highs if countries ramp up investment and adopt sustainable growth-oriented policies. Combining an all-out investment push to achieve climate and development goals with reforms to increase labor force participation rates—especially of women—could increase potential growth by as much as 0.6 percentage points per year.

In the end, the long-term solution will require better debt management and monetary policies and faster global trade and investment growth. It’s possible to put the global economy into an extended winning streak again. But it will require determination on the part of policy makers both at home and abroad. The World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s Annual Meeting in Marrakech next week is the right place to start building back the global economy.

Source : World Bank