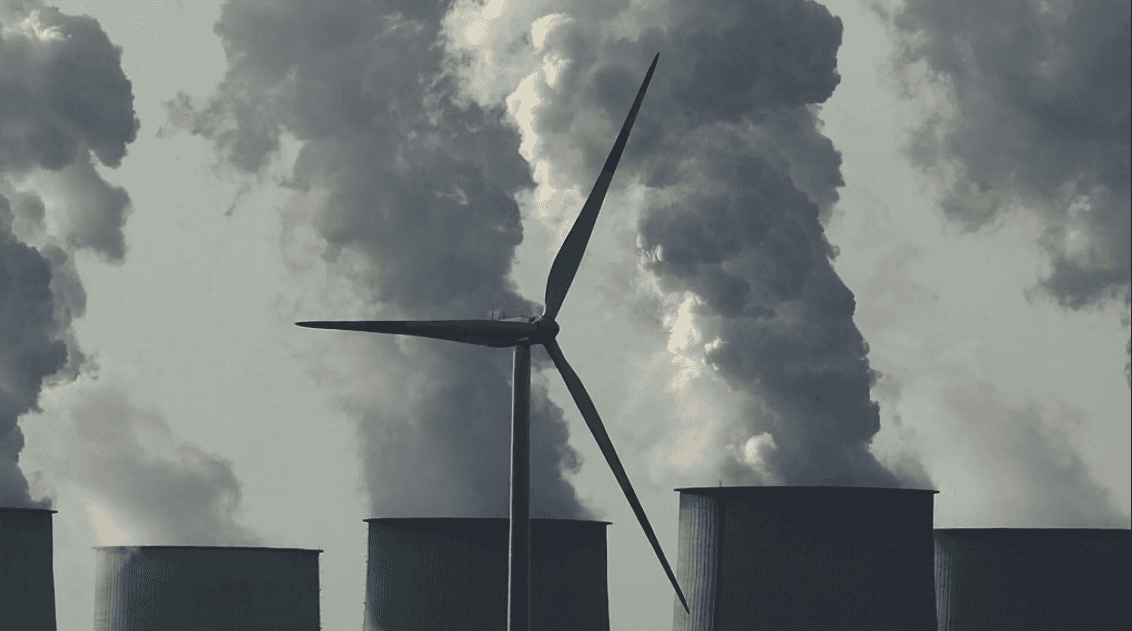

ASML is Europe’s most valuable tech company, but lately it finds itself caught in a conflict between its commercial profits and its commitment to human rights. ASML makes the complex machines required to construct advanced microchips, and it sells many of these machines to China, where they are used to make microchips for among other things weapons used by the Chinese military and surveillance systems used by the Chinese state.

Over the past few months, the United States has been ramping up its export controls to limit China’s access to advanced microchips. After the latest round of U.S. controls fell into place in early October, much attention was paid to how they can limit China’s development of military technologies, particularly nuclear weapons and hypersonic missiles. Less attention has focused on another key motivation for the controls: limiting China’s extensive systemic human rights abuses.

China’s surveillance state is increasingly high-tech. Supercomputers in China are powered by advanced chips that ASML’s machines help build, and run AI programs to analyze the data generated by omnipresent cameras, sensors, and electronic eavesdropping. Beijing is using these technologies to enable totalitarian control of its 1.4 billion citizens particularly in Xinjiang, where the minority Uyghur population is brutally repressed and held en masse in prison camps.

While some have argued that we should not concern ourselves with what happens inside China, the surveillance threat is not confined to China’s borders. Beijing is exporting its surveillance technologies, along with its expertise, norms, and legal frameworks, to countries around the world. Such a deliberate effort by the Chinese Communist Party leadership is meant to erode and subvert democratic principles around the world. Such actions undermine the core interests of the Netherlands, the European Union, and its allies and partners.

Beijing is using surveillance technologies to enable totalitarian control of its 1.4 billion citizens.

Others including ASML CEO Peter Wennink have objected to the U.S. export controls on grounds of economic competitiveness. Why should a small handful of companies be burdened by limits on what they can sell? ASML and its international arm, ASMI, produce world-leading technologies in a sector of foundational importance to the global economy. The Dutch are rightfully proud of these firms and the companies’ executives understandably will defend their interests. But harmonization of controls with the United States could limit China’s access to advanced microchips, all without disadvantaging Dutch firms.

It’s important to note that the recent U.S. controls restricted only American-made machines, for which there are no foreign-made alternatives. With this policy, Washington is signaling that it is willing to constrain U.S. competitiveness first, in order to underscore the seriousness and urgency with which it views Beijing’s military modernization and human rights violations. The U.S. controls also demonstrate trust in the U.S.-Netherlands relationship, as Dutch firms can still build and sell the machines internationally that U.S. firms now cannot. The Biden administration appears confident that the bonds between the allies are such that Dutch firms won’t take advantage of the situation by gobbling up the market share of its U.S. competitors.

This demonstration of trust leaves the door open for discussions that could encourage leaders in the Hague to develop complementary policies. It’s a question of crafting policy to be “koopman en dominee” (“merchant and pastor”) instead of “koopman of dominee” (“merchant or pastor”). The export controls announced by the United States strike a careful balance between upholding ethical principles, addressing national security risks, and considering industry motivations and need to generate profits. In other words, these actions are not an either/or proposition but balance doing the right thing with preserving industry’s viability and competitiveness.

As a leading advocate of human rights for all, the Netherlands and its largest tech company have been handed an opportunity to lead the world by example in the responsible uses of technology.

ASML and its international arm, ASMI, derive around 16 percent of their annual revenue from sales to customers in China, but only up to 10 percent of these sales are for the tools needed for the advanced microchips targeted by U.S. controls. If the Netherlands adopted the U.S. controls, ASML and ASMI could continue most of their sales to China. And new fab construction in Europe, the United States, South Korea, and Japan provides ample opportunity for the company to generate revenue in other markets.

Recently, Peter Wennink, the CEO of ASML, when asked about ASML’s business in China, answered with a question of his own: “If human rights are being violated: by whom and what impact do you have on this as a company?” In the case of ASML and ASMI, the answer is a whole lot. As a leading advocate of human rights for all, the Netherlands and its largest tech company have been handed an opportunity to lead the world by example in the responsible uses of technology.

Source : RAND CORPORATION