To Ensure a Sustainable Future, We Must Reevaluate the Approach to Cost-Benefit Analysis

Traditional cost-benefit analysis tends to undervalue long-term investments, particularly in natural capital, as it often prioritizes short-term gains and overlooks impacts beyond a 20-year timeframe. In order to rectify this, we need to implement policies that prioritize long-term sustainability and consider the following modifications to our current approach to cost-benefit analysis:

The utilization of economic tools in decision-making for developmental projects is crucial, as economic analysis helps decision-makers validate investments and ensure their economic viability. However, it is essential to acknowledge that cost-benefit analysis is a social construct shaped by prevailing values, such as our preference for present over future benefits, prioritizing capital over human resources, and favoring infrastructure rich in steel and cement over environmental considerations.

The inherent challenge with cost-benefit analysis lies in its bias towards the present, which impedes investment in long-term projects that incorporate natural capital. The common practice of discounting future benefits to their present value reflects our inclination towards immediate gratification. However, this method fails to acknowledge that investments in natural capital take time to mature and yield incremental benefits over an extended period.

The concept of “discount rates” plays a crucial role in cost-benefit analysis. Economists use the discount rate to represent future costs and benefits in present-day terms, aiding policymakers in assessing the viability of a project. However, the use of higher discount rates devalues future benefits compared to lower rates, indicating an undervaluation of long-term benefits. This becomes problematic when considering the long-term effects of issues like climate change.

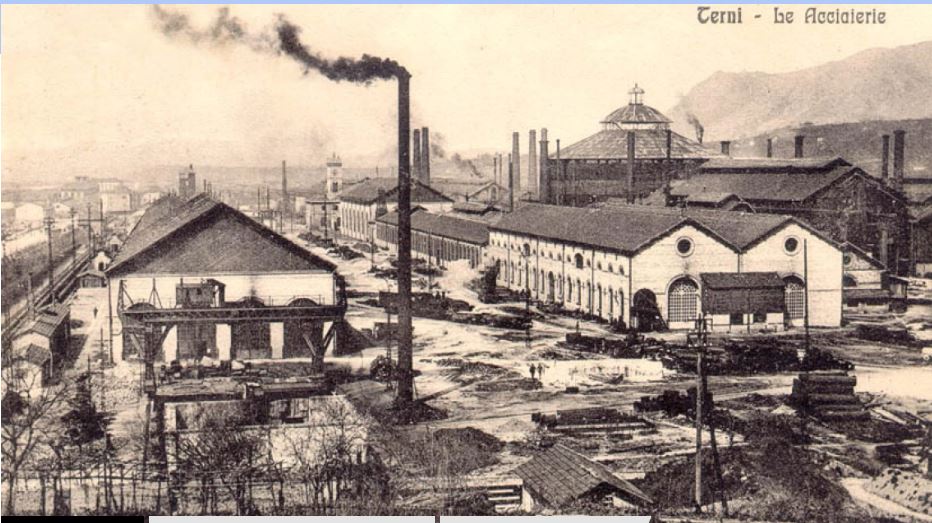

Traditional cost-benefit analysis has limitations in its scope. Initially developed for short to medium-term physical capital investments, such as roads, dams, buildings, and bridges, the method assumes an operating life of less than 25 years, with benefits materializing soon after construction.

In contrast, projects focused on forestry, pollution remediation, and climate adaptation highlight the fact that natural capital requires years to develop and yields benefits that extend far into the future. The ecological and ecosystem values derived from afforestation or rehabilitation efforts may take decades or even centuries to fully restore. The benefits from these natural capital investments progressively increase over time, unlike the rapid returns of man-made capital investments.

Given the escalating socio-environmental, cultural, and climate-related challenges we face, we now require much longer time horizons in cost-benefit analysis, extending beyond 25 years and potentially up to 100 years. The application of constant positive discount rates overlooks the effects beyond 25 years and results in less consideration of future benefits. Higher discount rates imply a greater opportunity cost and undermine the long-term benefits of climate mitigation and adaptation investments, burdening future generations with the challenges we fail to address today.

This imbalance between the needs of current and future generations has ignited substantial debate about incorporating inter-generational discounting. Investment decisions involving substantial initial costs and larger future benefits become more favorable when discount rates approach zero. As the benefits of investments to counter the potential impacts of climate change will accrue far into the future, employing the lowest possible discount rate becomes less discriminatory.

The concept of declining discount rates has gained traction in recent years, also known as hyperbolic discounting. This approach assigns equivalent value to medium and distant futures, with the discount rate decreasing as the time horizon lengthens. This practice is based on the understanding that individuals’ discount rates tend to decline over time. As early as 1998, Weitzman proposed the use of varying rates depending on the lifespan of the project.

Different countries have adopted diverse strategies to address this challenge. For example, the United Kingdom has officially endorsed declining discount rates, transitioning from a rate of 3.5% in year 10 to a rate of 2.