A key barrier to economic development is that while new technologies can offer substantial productivity gains, firms in poorer countries often do not adopt them. This column uses firm-level data to track the adoption of the key technology of the 19th century – the steam engine – during Sweden’s rapid industrial take-off. Much like in many developing countries today, Swedish firms were generally too small to profitably adopt the new technology. The authors document the central role of an institutional innovation – the modern corporation – and demonstrate that when firms were given the opportunity to incorporate, they expanded and adopted steam technology.

A key puzzle is why many new technologies that can raise productivity are adopted so slowly. For example, major new technologies over the past two centuries – such as automobiles, electricity, or telephones – have an average adoption lag of almost half a century (Comin and Hobijn 2010). To account for the slow rate of diffusion, a recent body of work underlines the role of ‘technical literacy’ (Juhász and Weinstein 2024) or complementary organisational knowledge (Squicciarini et al. 2020). Another potential explanation is that firms in poor countries are often too small to profitably adopt new technologies.

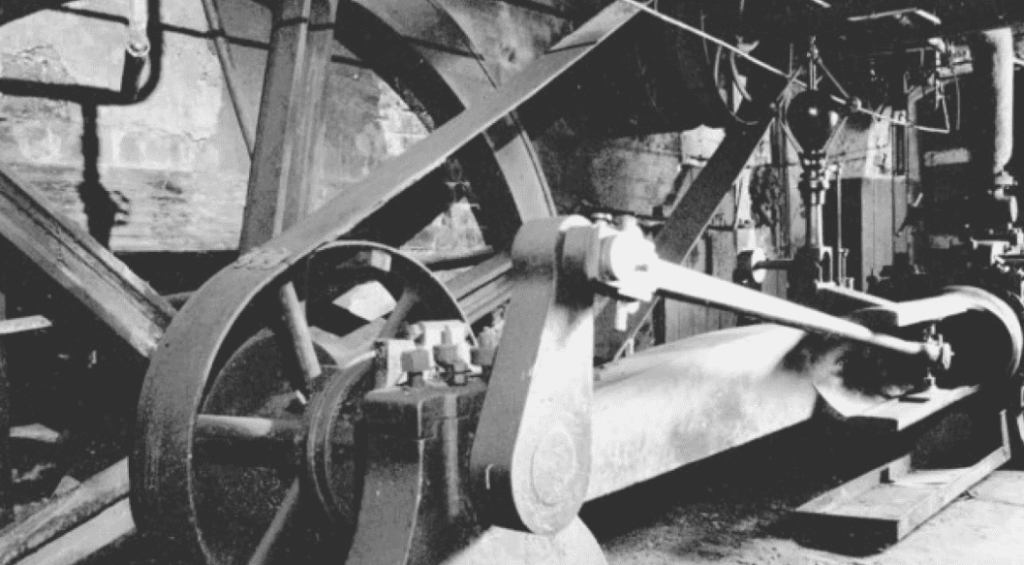

In a recent paper (Berger and Ostermeyer 2024), we describe how an institutional innovation – the modern corporation – was a key driver of technology adoption during Sweden’s rapid industrial take-off in the late-19th century. We focus on the diffusion of the central technology of the Industrial Revolution: the steam engine. The modern steam engine was developed by James Watt in mid-18th-century Britain, but it took more than 100 years to diffuse across American and European industries and for it to have a significant aggregate economic impact (Atack et al. 2022, Crafts 2004).

Figure 1 The diffusion of steam technology

Note: The figure shows the share of establishments that used steam, water, and animal power.

Around the mid-19th century, Sweden was an agricultural and rural economy with industrial technology levels that lagged significantly behind Europe’s leaders. Almost a century after Watt’s invention, only about one in ten Swedish firms had installed a steam engine (see Figure 1). Much like in many developing countries today, Swedish firms faced substantial barriers to adopting new technologies. In particular, the transition to steam power required firms to operate on a considerably larger scale. Yet most production was carried out in small artisan shops employing a handful of workers, which were far too small to profitably use steam. However, Figure 1 shows that Sweden’s rapid industrial breakthrough starting around 1870 involved a widespread diffusion of steam technology. What enabled this rapid transition?

We focus on a key institutional innovation: the limited liability corporation. Limited liability was codified into law in most European nations around the mid-19th century. In Sweden, the Companies Act of 1848 introduced the modern corporate form. By the 1860s, it had evolved into a liberal system of general incorporation as in Britain, Germany, and the US. Before the advent of the modern corporate form, owners had unlimited liability. Expanding operations or investing in new technology was thus risky. By granting owners limited liability, the corporate form may have facilitated the adoption of steam by lowering risks involved in major capital investments, as well as by improving access to debt and equity markets.

Figure 2 Incorporation and steam adoption across Swedish industries

Note: The figure shows the share of establishments that were corporations and used steam respectively across industries.

Very few Swedish firms were organised as corporations around the mid-19th century, but the corporate form quickly gained popularity. By the mid-1890s, approximately 20% of firms were corporations. This shift involved both the foundation of new corporations and the conversion of existing firms into the corporate form. Notably, the corporate form diffused within the same industries that adopted steam in the late 19th century (see Figure 2).

Analysing the role of the modern corporation in shaping technology diffusion requires detailed data on both the organisational form and technology use of firms. Here, we make use of Sweden’s historical manufacturing census, which allows us to track each industrial firm year-by-year throughout the 19th century. In a collaborative effort (Almås et al. 2024), we have recently digitised these data, providing a rare opportunity to examine how firms’ technology use varies with their organisational form.

Our data reveal that corporations were more than three times as likely to use steam compared to firms that were not incorporated. However, this simple association could also reflect factors such as corporations’ tendency to be larger or located in urban areas. Since our data allow us to track firms over time, we can examine firms before and after incorporation and compare them with firms that are similar but that do not incorporate. Figure 3 shows that firms were substantially more likely to adopt steam power after incorporation and that the effect is increasing over time. Case study evidence of industrial firms further shows that firms leveraged the corporate form to finance broader technological changes, expand operations, and adopt more modern management practices.

Figure 3 The effect of incorporation on the adoption of steam power over time

Note: The figure shows the probability of firms adopting steam power in the following five years after incorporation.

Another key takeaway of our analysis is that the diffusion of the modern corporate form particularly helped more marginal firms to grow and eventually adopt steam. We find that initially smaller firms located in rural areas with worse access to the banking system benefitted more from incorporation. Incorporation also seems to have been especially beneficial during earlier phases of industrialisation when access to capital was scarcer. Notably, these findings contrast evidence from less liberal incorporation systems (Gregg 2020).

This year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences highlights the role of institutions as central to understanding why some countries are wealthy while others remain poor (Dell 2024). Today, few would dispute the role institutions play in shaping cross-country income levels. Yet there remains a remarkable scarcity of evidence on which institutions drive growth. As described in this column, a liberal system of incorporation was central to enabling Swedish firms to adopt modern production technologies that ultimately contributed to Sweden’s rise as a modern industrial nation. As such, it also provides an example of how a specific institution contributes to shaping income and productivity differences across countries.

Source : VOXeu