Global inflation has once again taken centre stage for households and policymakers, stressing peoples’ finances, undermining their savings patterns, and threatening long-term financial security. This column examines how much financial literacy, including knowledge of inflation, drives people’s financial decision-making. Simple measures which have been used around the world confirm strikingly low levels of financial literacy, with consequences for how people manage their personal finances. It is becoming increasingly important to focus on the new field of financial literacy, not only for research by also for teaching and for policy.

Consumers in the modern economy must make a wide range of complex financial decisions with potentially long-lasting consequences. The recent rise in inflation, the spread of online financial apps for borrowing and investing, new ways to make payments (‘buy now, pay later’), and the availability of new asset types (e.g. crypto) have all contributed to the need for financial know-how. Unfortunately, a great deal of evidence indicates that peoples’ decisions often land them in debt and financial distress (Keys et al. 2020, Koedijk 2015).

Measuring financial literacy

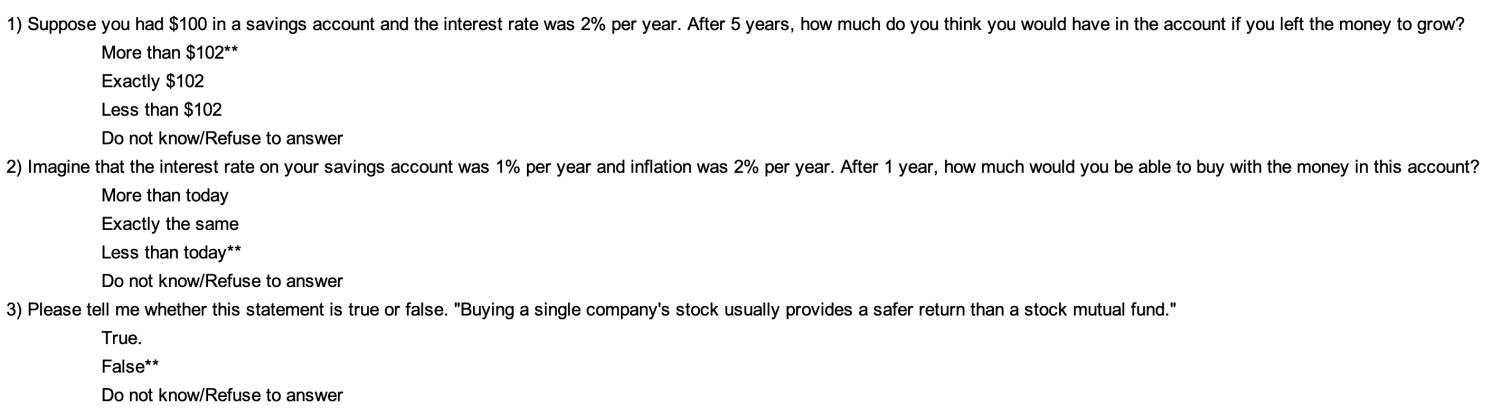

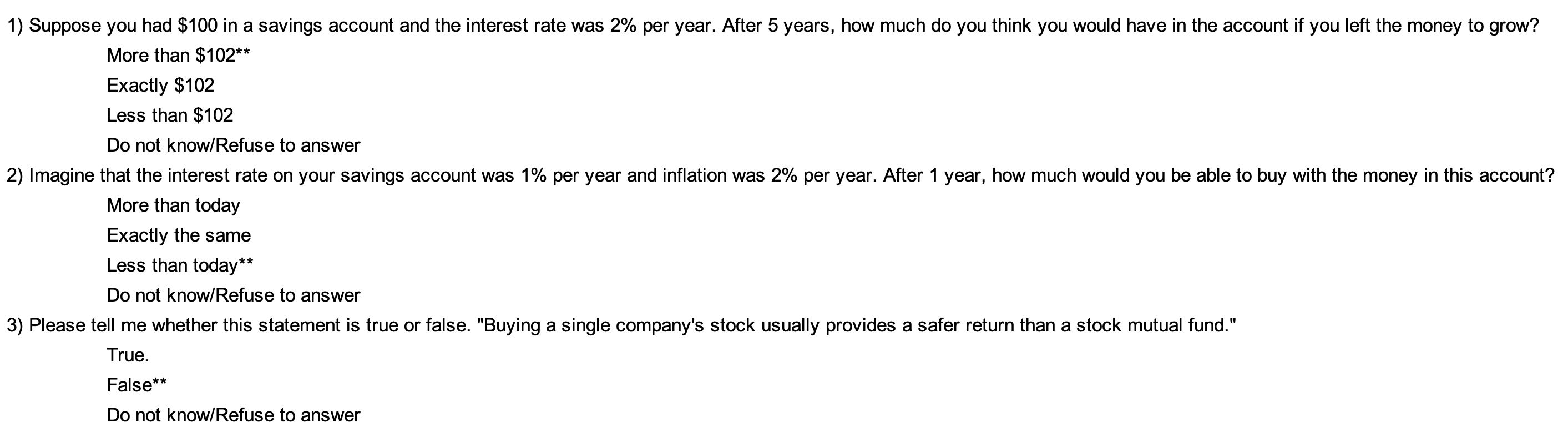

For this reason, and after noticing the changes in pensions and access to credit, we decided in the early 2000s to investigate patterns of financial literacy, defined as people’s knowledge of and ability to use basic financial concepts in their everyday financial decision-making (Lusardi and Mitchell 2014). This effort produced what has become known as the ‘Big Three’ – a short set of questions that proves to be extremely useful measures of how well people understand basic financial concepts (Lusardi and Mitchell 2011). Table 1 lists these questions along with answers, using the most recent data available from a national survey of consumer finances.

Table 1 The ‘Big Three’ financial literacy questions and answers

Note: Correct answers indicated with two asterisks.The Big Three questions, designed by Lusardi and Mitchell, have been used in numerous international comparisons of financial literacy

Source: The Big Three originated with Lusardi and Mitchell (2011a).

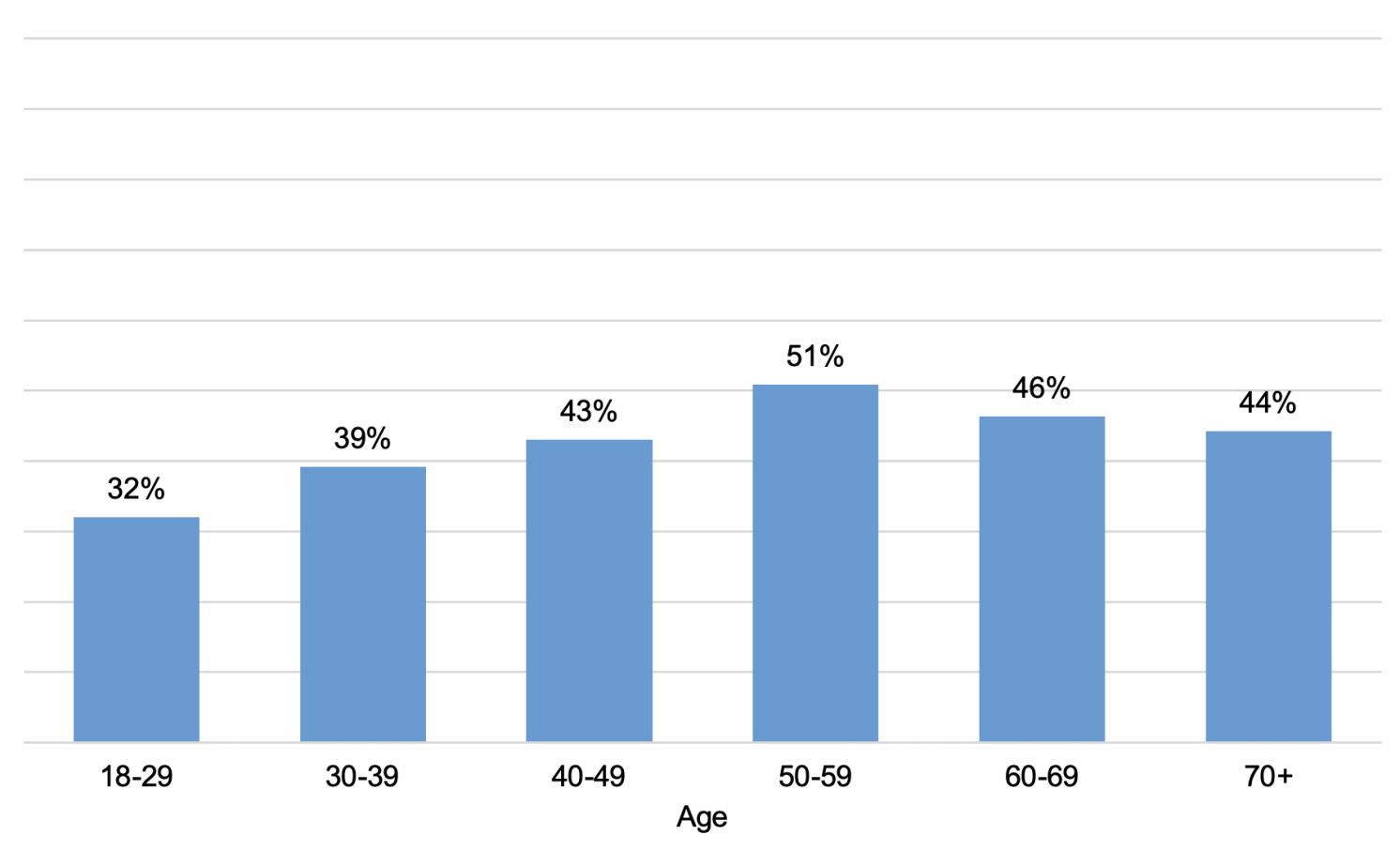

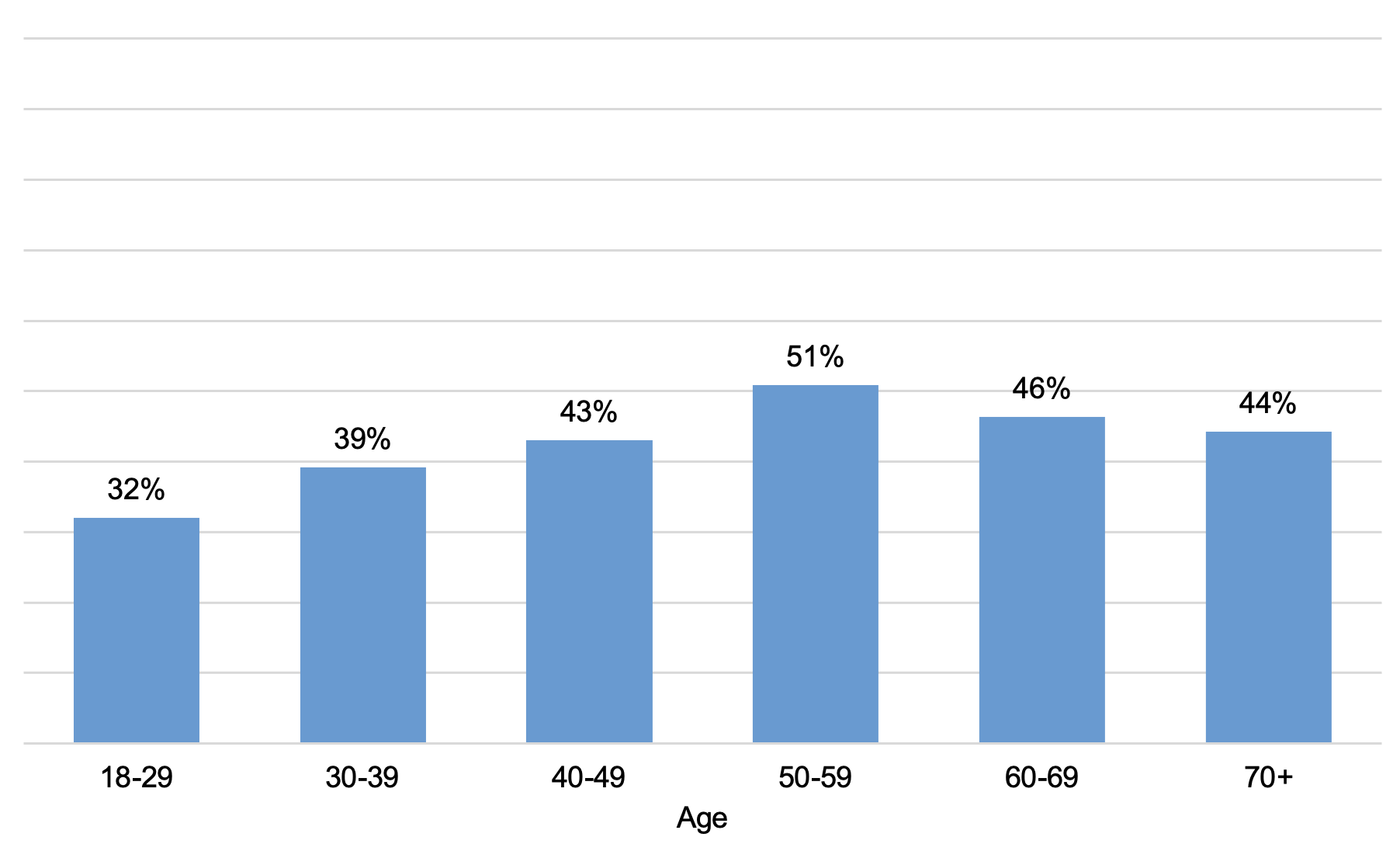

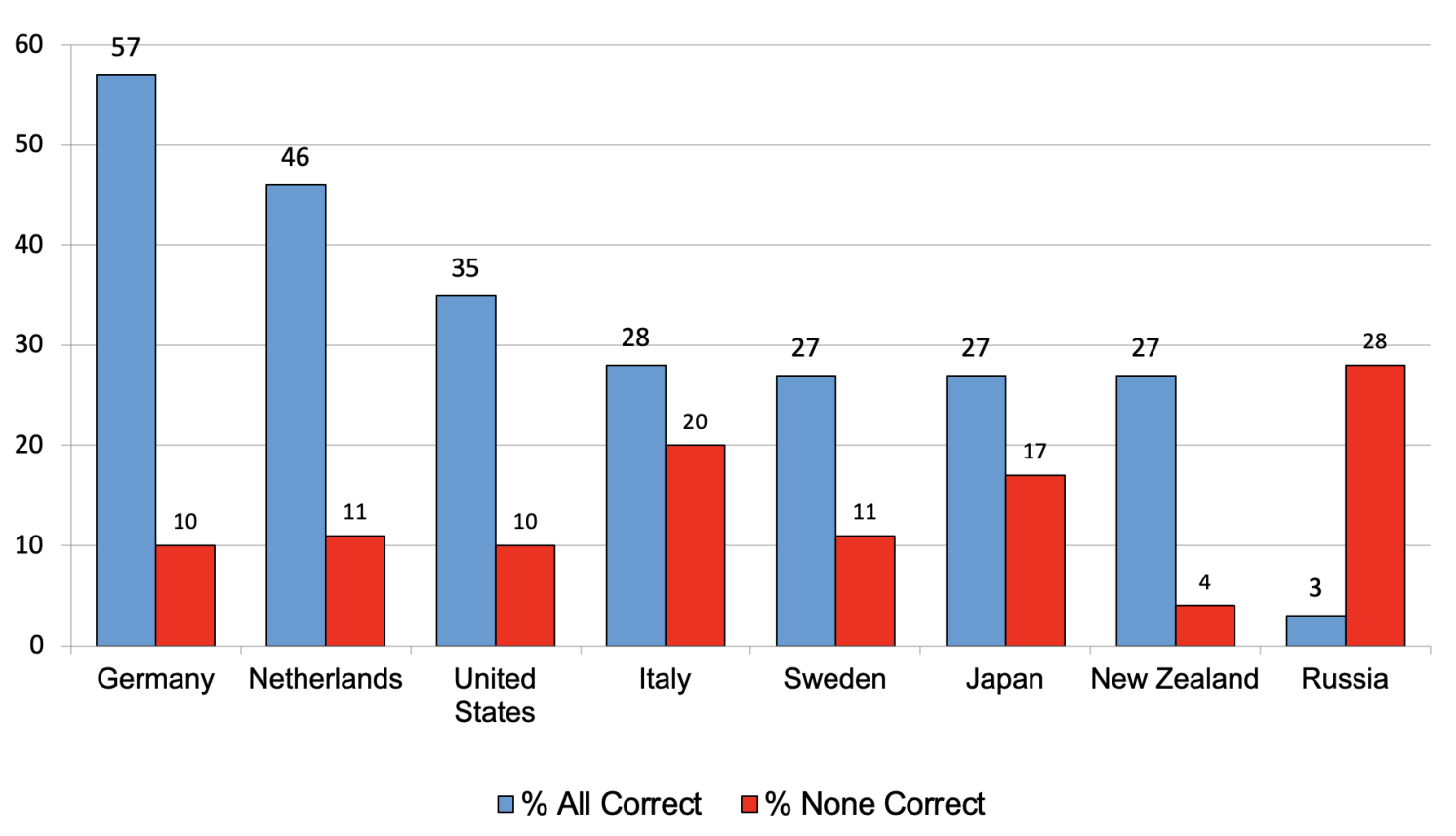

Despite the fact that these questions were intended to assess knowledge of the ABCs of personal finance, fewer than half of the respondents queried in this nationally representative survey in the US got all three correct, even among older persons having already made numerous financial decisions over their lifetimes (Figure 1). Our Big Three includes a question about inflation, a timely economic concern of late, and we have found that a substantial fraction of the population – especially the young – does not understand how inflation erodes purchasing power.

Figure 1 Percent of respondents answering all Big Three questions correctly, by age

Source: Authors’ calculation, US Survey of Consumer Finances (2019).

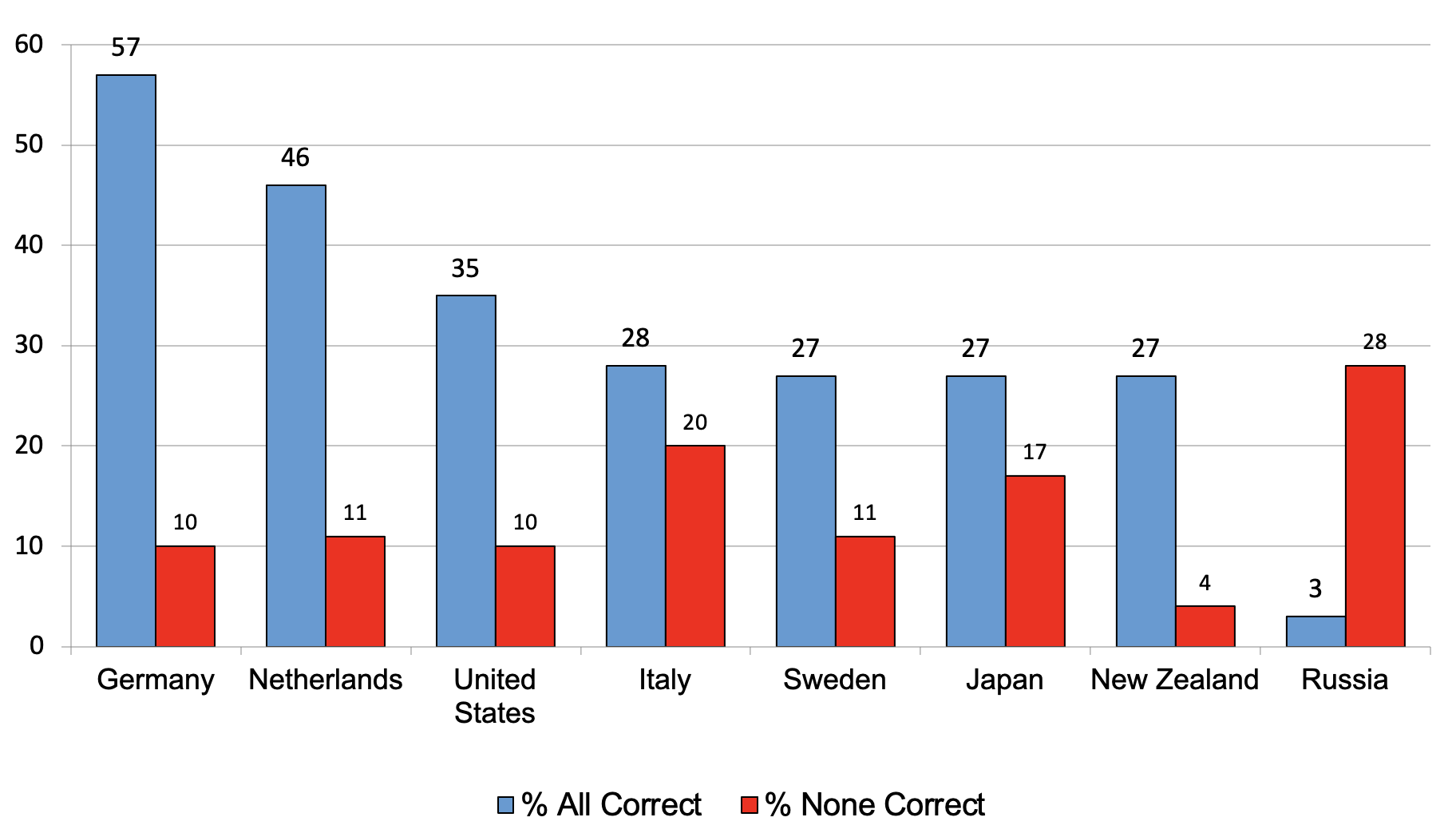

Similar patterns for the Big Three also hold in most developed countries, as indicated in Figure 2, and people know even less about emerging economies (Lusardi and Mitchell 2014). Additionally, the groups who are less financially similar are strikingly similar across countries. That is, young, women, the less-educated and low-income, and racial/ethnic minorities all display low financial literacy, making them even more financially vulnerable than other standard indicators, such as savings, would predict.

Figure 2 Financial literacy in several countries

Source: Lusardi and Mitchell (2011)

We have also extended our measure of financial literacy to incorporate other relevant financial concepts. These extended measures of financial literacy, including our Big Five measures, cover additional areas of financial decision-making, and they confirm most of our earlier findings using the Big Three (Lusardi and Mitchell 2023).

Financial literacy matters

This topic is important since the more financially literate engage in savvier financial behaviours than do their counterparts. For example, they are more likely to save for the short and the long term, invest in stocks, earn higher (risk-adjusted) investment returns, and can better manage their debt (Lusardi and Mitchell 2023). We have also shown that financial literacy, when seen as a form of human capital investment, can be incorporated into traditional economic models of saving under uncertainty. Its relevance cannot be overstated: financial literacy accounts for 30-40% of observed retirement wealth inequality (Lusardi et al. 2017).

Another way to assess the importance of knowledge is to look at the effects of financial education. A recent meta-analysis covering the most rigorous programmes (randomised controlled trials, or RCTs) in 33 countries across six continents yielded three major conclusions (Kaiser et al. 2022). First, financial education has important positive effects on both financial knowledge and behaviour. Second, its impact is three to five times larger than reported in prior studies. Third, financial education programmes are cost-effective and the effects are similar to other education programmes.

Moreover, its importance can be seen in the burgeoning body of research spurred not only by data and measurement but also by the renewed interest in this topic among academics and policymakers globally. As a consequence of opening this field, financial literacy research has now grown exponentially in recent decades. For instance, an online search for the term “financial literacy” in the Social Science Citations Index uncovered very few citations over the period 1994-2004; now, the total number exceeds 3,000 per year (Kaiser et al. 2022). We also recently launched the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing published by Cambridge University Press, aiming to publish the most rigorous research on these topics. Moreover, the economics profession now recognises financial literacy as an official field of study with its own JEL code (G53).

Implications

As this new field has developed, several implications have been identified for future research, teaching, and policy. Specifically, our metrics for measuring financial literacy have been adopted across the world, and they are proving to be good predictors of financial behaviour. The Big Three have been included in over 40 studies in Europe, Latin America, and Asia, and versions of these questions have been included in a global financial literacy survey (Klapper and Lusardi 2020). We have also shown that financial literacy can be incorporated into standard intertemporal models of consumer behaviour. Indeed, not doing so limits understanding of the determinants of wealth. Accordingly, incorporating financial literacy into standard economic models of consumption and saving is essential if researchers wish to incorporate a key explanation for observed large differences in wealth near retirement.

In addition, the critical role of financial literacy skills has now been recognised by colleges and universities. Motivated and guided by our research findings, we began offering personal finance courses at our own universities, starting in 2013. Just as aspiring chief financial officers (CFOs) regularly learn corporate finance in college and business schools, regular consumers also need rigorous training to manage their money, save, invest, and avoid running out of money in retirement.

Our research also provides insight into what such courses should teach. In the US, national standards for financial literacy have been established, outlining what should be covered in personal finance courses in school. We have extended those standards in our courses, drawing on both theory and empirical evidence on financial literacy.

Regarding policy, over 80 nations have established committees to design and implement national strategies for financial literacy. The European Commission in its capital markets union action plan has added financial literacy as a key objective for empowering citizens. More recently, the Commission has issued a report on financial literacy data collected in 2023 across the 27 EU nations, using questions similar to the Big Three. Countries should add measures of financial literacy to their national statistics; research has shown it is linked to many indicators of financial well-being.

Additionally, the fact that so many people lack financial knowledge not only limits their ability to use their resources to the fullest but also contributes to macroeconomic problems and financial instability. For example, people who do not understand inflation may do a poor job of budgeting. Additionally, consumers who fail to understand risk and risk management may underinsure, and families suffer when they lack precautionary savings to hedge against even small shocks, much less against the massive economic turmoil generated by the recent pandemic. As with population health, prevention is often better and less costly than the cure.

Source : VOXeu