Developing countries are facing mounting pressures to incorporate environmental concerns into their policy reform agendas, leading to concerns that traditional development assistance may be crowded out. This column argues that under weak institutions, which can allow a relatively large share of tax receipts to leak out of the economy, common policy actions like levying taxes to address the environmental externality can, instead, aggravate it. Focusing solely on environmental policies, and ignoring other development objectives, can therefore be self-defeating.

Developing countries are facing mounting pressures to incorporate environmental concerns into their policy reform agendas. On one hand, trade policy measures such as the European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism aim to facilitate pollution mitigation efforts outside advanced economies (Young 2022). On the other hand, growing emphasis on environmental and/or climate reforms seems to reconfigure official aid to developing countries (Ramachandran 2023). Parties to these matters are increasingly concerned with the possibility of the emerging focus on climate and environment crowding out traditional development assistance.

In a new paper (Karayalcin and Onder 2024), we urge against such crowding out. Our analysis shows that under weak institutions, which include incomplete property rights in nature-based assets and the leakage of a portion of tax receipts from the economy, common policy actions like levying taxes to address the environmental externality can, instead, aggravate it. Therefore, focusing solely on environmental policies, and ignoring other development objectives, can be self-defeating.

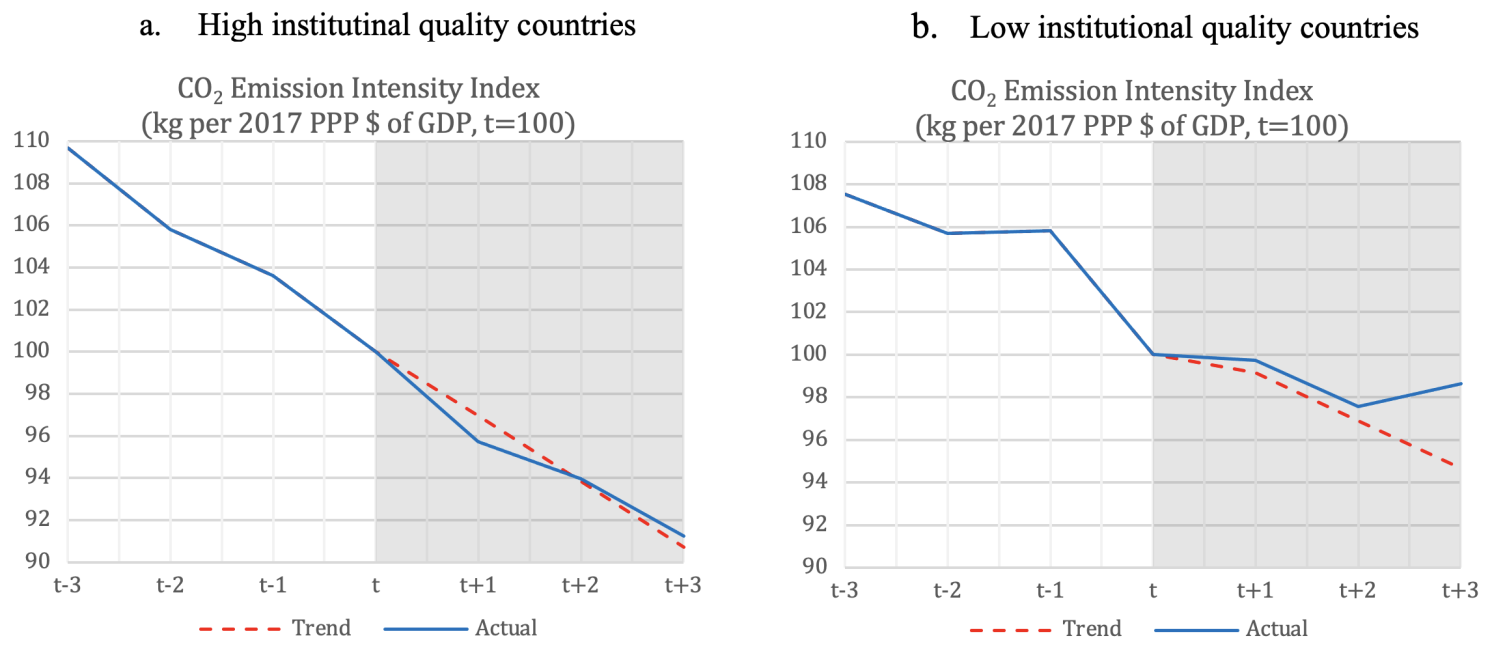

In the absence of comprehensive evidence, our analysis is motivated by early observations of the relationship between institutional quality and mitigation efforts across a small number of countries. Figure 1 shows how the CO2 emission intensity of GDP has evolved around the implementation date of CO2 taxes across countries. For those countries with above-median institutional quality, emission intensity remained largely on track after the introduction of the carbon tax. In contrast, for countries with below-median institutional quality, the post-tax reduction in the CO2 emission intensity fell short of their pre-tax trends. While purely descriptive and driven by a small number of cases, this example nevertheless suggests a potential role for institutions in shaping future environmental efforts.

The framework

Our analysis employs a general equilibrium model with two sectors – agriculture and manufacturing – following conventional approaches like Matsuyama (1992). While manufacturing only employs labour, agriculture employs both labour and a nature-based input (land). Workers are mobile across the sectors, responding solely to differences in wages. Preferences are non-homothetic: a subsistence level of food consumption sets the income elasticity of demand for food to less than unitary.

In the benchmark scenario, the economy is assumed to be closed and decentralised. It also has weak institutions, including (i) incomplete property rights over nature-based assets, leading to dynamic distortions (overexploitation of the natural asset from a social point of view); and (ii) administrative weaknesses such as elite capture or inefficiencies in tax collection, allowing a portion of the tax proceeds to leak out the economy.

Within this framework, we investigate whether policymakers can reduce the excessive exploitation of the natural asset simply by levying a tax on agricultural output (to be rebated to consumers) within a decentralised setup.

Figure 1 Carbon intensity of economic activity across countries with carbon taxes

Notes: Figures show countries who implemented CO2 tax reforms (at year t) with complete emission data around the reform date (14 countries) for the period 1990-2020. Emissions use World Development Indicator data at annual frequency, and they are normalized for the reform year, which varies across countries Institutional quality is based on “Rule of law: percentile rank” indicator of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (“high” is above the population median and “low” is below it).

A seemingly paradoxical result

In the benchmark case, when a relatively large share of tax receipts leaks out of the economy, environmental taxes can increase the exploitation of natural resources instead of decreasing it. This counter-intuitive result is driven by three channels that are common to multi-sector general equilibrium models. First, environmental taxes reduce the marginal productivity of labour in agriculture, driving workers towards manufacturing. Second, in a closed economy, this negative supply shock leads to higher food prices, hindering the outflow of labour from the sector. Third, with non-homothetic preferences, adverse income shocks increase demand for food, reinforcing the price effect. Overall, when leakage is large enough, the demand-side effects can dominate the supply-side ones, thereby increasing the exploitation of natural resources.

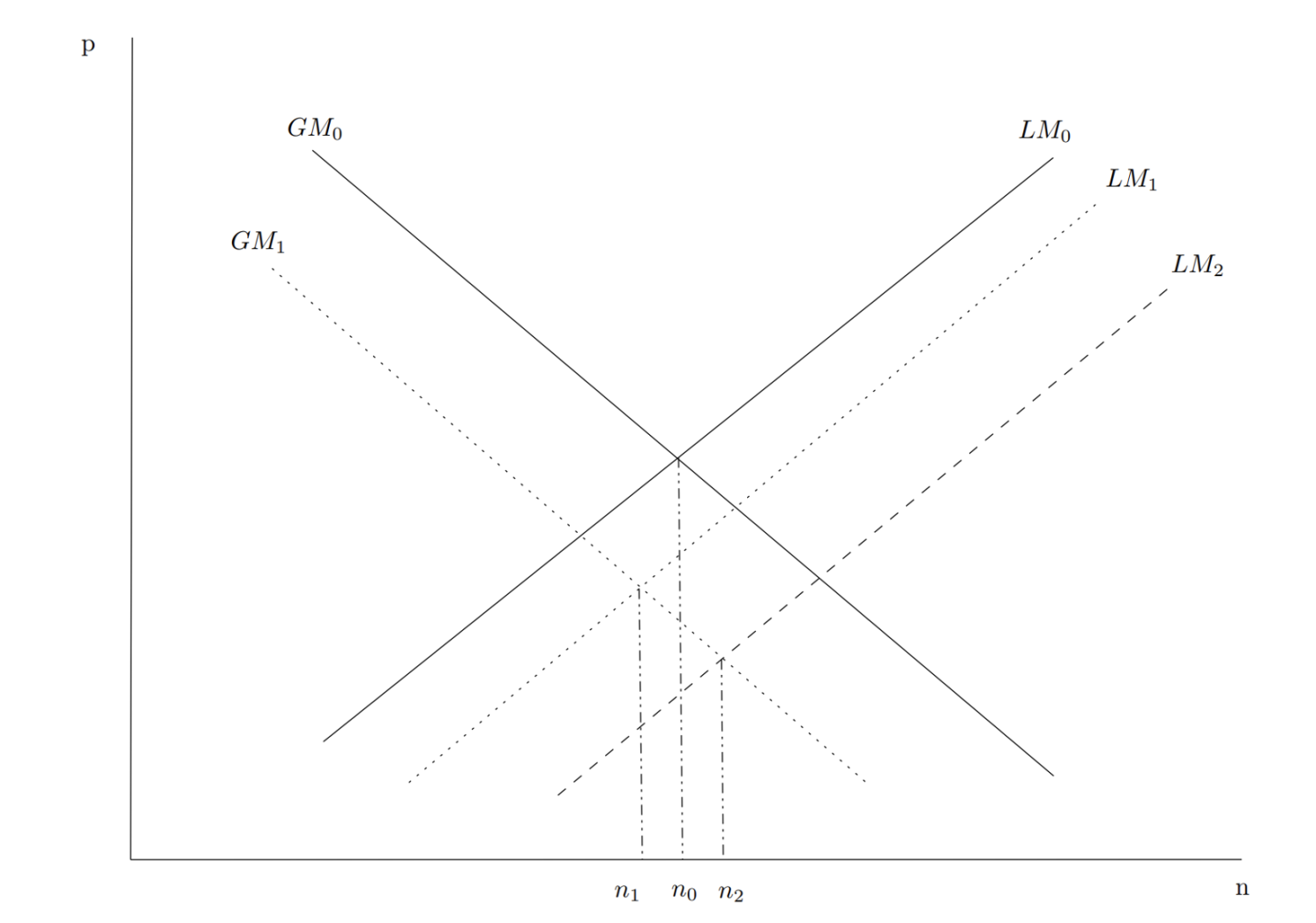

Figure 2 illustrates these mechanisms through the lens of goods (GM) and labour market (LM) equilibrium conditions. Given initial labour allocation (n_0), a tax on agricultural output (τ) lowers the supply of the agricultural good, decreases the relative price of manufactures, and shifts the GM0 curve down to GM1. It also reduces the marginal productivity of labour and the wage rate in agriculture, and, given p, shifts the LM curve to the right, increasing n. Though the effect of these shifts is to reduce p unambiguously, whether equilibrium n rises or falls depends on the relative magnitude of the shifts in GM and LM curves.

Figure 2 Goods and labour market equilibrium on relative price (p) and employment (n) plane

Notes: Figure shows the goods market (GM) and labour market (LM) equilibrium conditions on relative price (p) and employment (n) plane for manufacturing.

Given a potentially positive relationship between taxes on agricultural output and employment in agriculture, our analysis suggests that optimal policy in the face of an environmental externality can be a subsidy when these general equilibrium effects are taken into consideration.

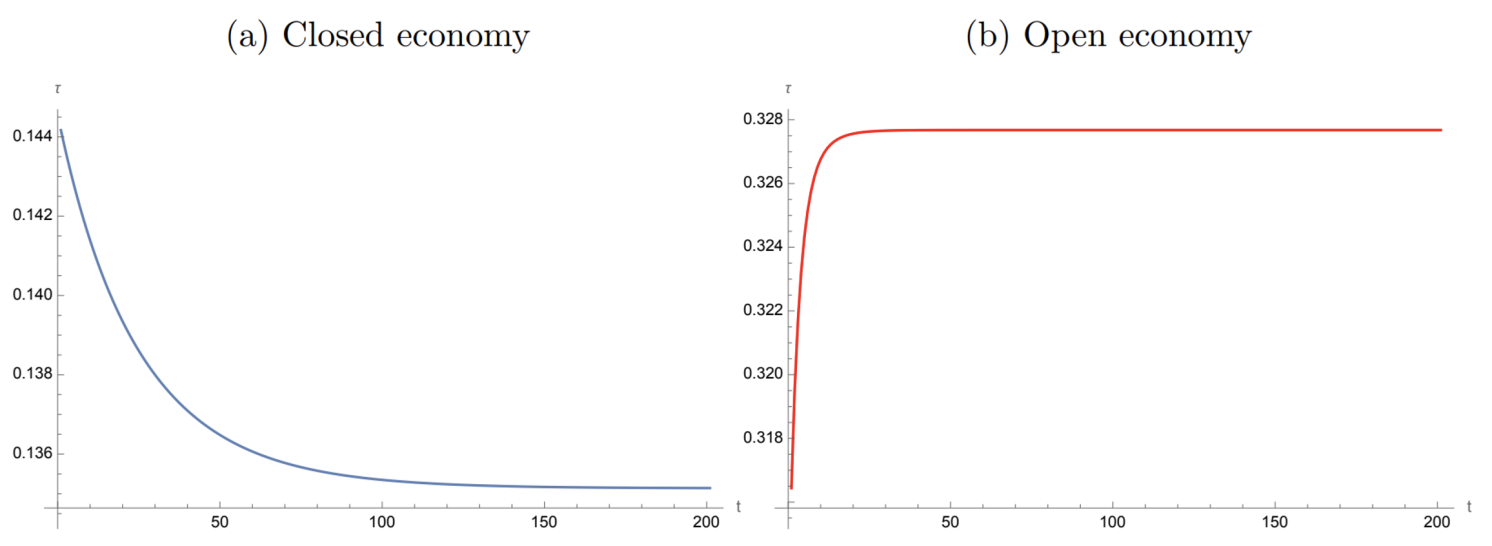

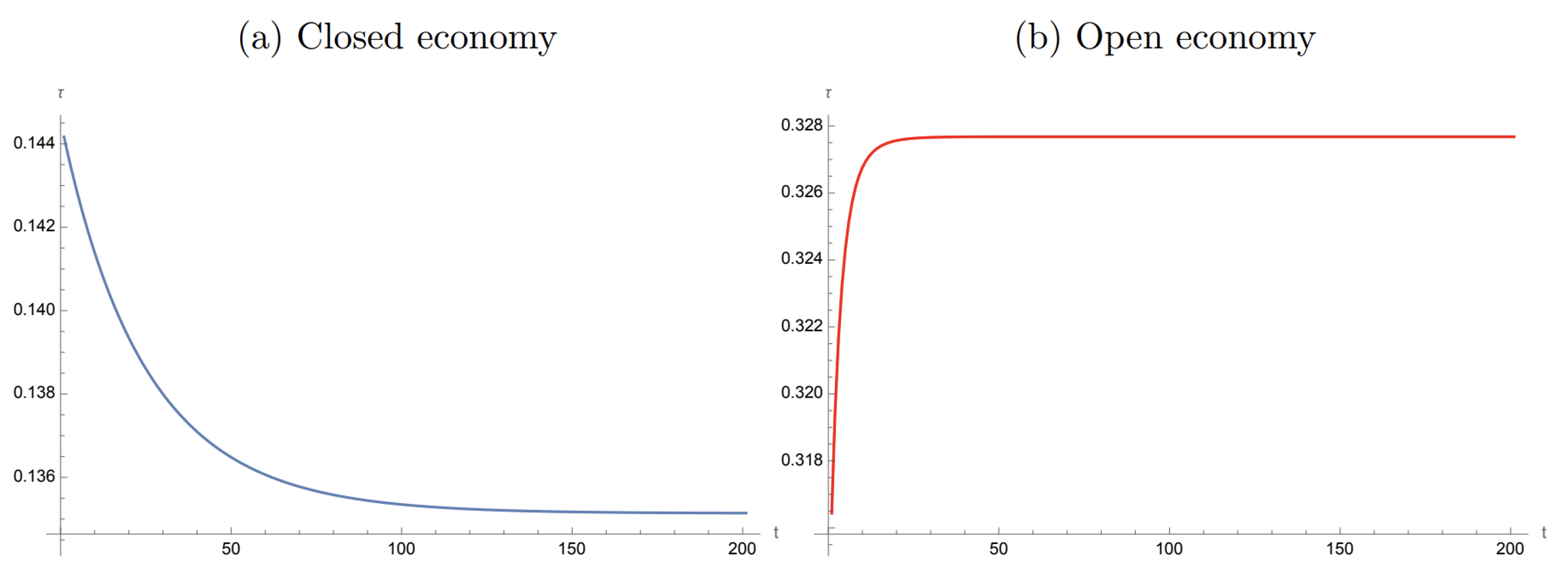

With these effects in mind, our numerical simulations show that the optimal policy responses to a climate shock, which reduces natural assets, can be opposite between closed and open economies (Figure 3). The shock reduces the marginal product of labour and wages in agriculture, pushing labour towards manufacturing, reducing the exploitation of the natural asset, in the open economy case. This reduces the optimal tax. In contrast, in a closed economy, the reduction in natural asset can increase agricultural employment by reducing the supply of the agricultural good and pushing up its relative price. If the optimal policy involves a subsidy under these conditions, the shock can increase the optimal subsidy for the same reasons.

Figure 3 Optimal taxes in closed and open economies

Notes: Figures show the adjustment of optimal taxes to a negative climate shock in closed and open economies. Parameter values are κ = 0, β = 0.3, σ = 0.8, and ρ = 0.5.

Potential areas for policy interventions

The extensions of our benchmark model highlight potential areas of intervention to weaken the paradoxical result – i.e. increase the threshold leakage parameter above which environmental taxes can increase the exploitation of the natural asset.

- A small increase in the elasticity of substitution between land and labour in agriculture can weaken the paradoxical result for initially small elasticities (the opposite is true for large elasticities).

- Economic openness can completely reverse the paradoxical result by fixing the prices and shutting down any demand-side considerations.

- International transfers can weaken the paradoxical result if they include a larger share of the agricultural good compared to the pre-transfer market equilibrium in the receiving country.

- An increase in mean-preserving inequality in income can weaken the paradoxical result by shifting aggregate demand towards manufacturing.

In all these cases, respective effects are manifested through the three channels identified in the benchmark model. Together, these results emphasise the need to consider environmental policies within the country’s broader development context, not in isolation.

Source : VOXeu